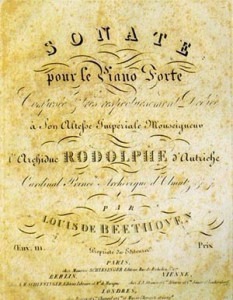

Title of Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 32, op. 111, first edition, with dedication

Piano Sonata No. 31 in A flat major, Op. 110

Stephen Kovacevich

Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111

Michelangeli

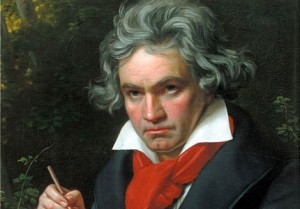

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a revolutionary man who lived and worked in revolutionary and tumultuous times. Much of his music — particularly his symphonies, piano sonatas and string quartets — represent a turning point in human artistic expression. Although he initially built his creations on the musical conventions, genres and styles of an inherited Classical tradition, his subsequent explorations and highly personal expressions allowed music to escape the superficiality of entertainment and virtuosity. Since psychology and drama become integral components of his musical syntax, Beethoven’s music is uniquely capable of revealing and uncovering the uneasy and sometimes troubling aspects of the human condition.

In his last works for solo piano, Beethoven turned the piano sonata, which originally had been a delightful form of home entertainment, into a profound and deeply personal statement. These sonatas inhabit an ethereal world that seems far removed from the everyday. Moving beyond the mere exploration of pianistic techniques and formal conventions, these works express something inwardly and introspective in Beethoven’s creative personality.

Although the final period of Beethoven’s life was marked by emotional upheavals and living in a soundless world, his compositions came to have a meditative and reflective character, the urgent sense of communication replaced by feelings of tranquility and passionate outpourings. This deep sense of intimate and delicate lyricism is frequently characterized as being excessively subjective. It was pointed out by Theodor W. Adorno, however, that the key to these works is found “in the peculiar manner of arresting conventions that are in fact not imbued and overpowered with subjectivity.” This simply means that in his late works, Beethoven interchangeably manifests form as expression, and expression as form; in essence, he is writing music about music. His musical language is becoming highly concentrated and abstract, relying on one hand on cantabile and declamatory recitatives — essentially basic forms of vocal expression — as the fundamental level of human communications. On the other, Beethoven evolved a new type of variation in which the theme becomes transformed or deconstructed to its fundamental components, suggesting a changing concept of musical unity, now seen as an evolution from within. Although contrapuntal textures, modality and fugue added a sense of personal retrospective, they should not merely be seen as persistent archaic urges; rather it is Beethoven’s attempt to control style and musical continuity in all textures. The underlying concern with fugue, as with variations and lyricism, however, was to mold these elements so that they could be integrally embedded into the formal matrix of sonata style.

Beethoven