Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo

The Mexican artist Frieda Kahlo (1907–1954) was one of the first women artists who brought ideas rarely explored by male artists to the foreground in her work, including chronic pain, postcolonialism, gender, and class. She also mixed realism and fantasy, adding strong autobiographical elements.

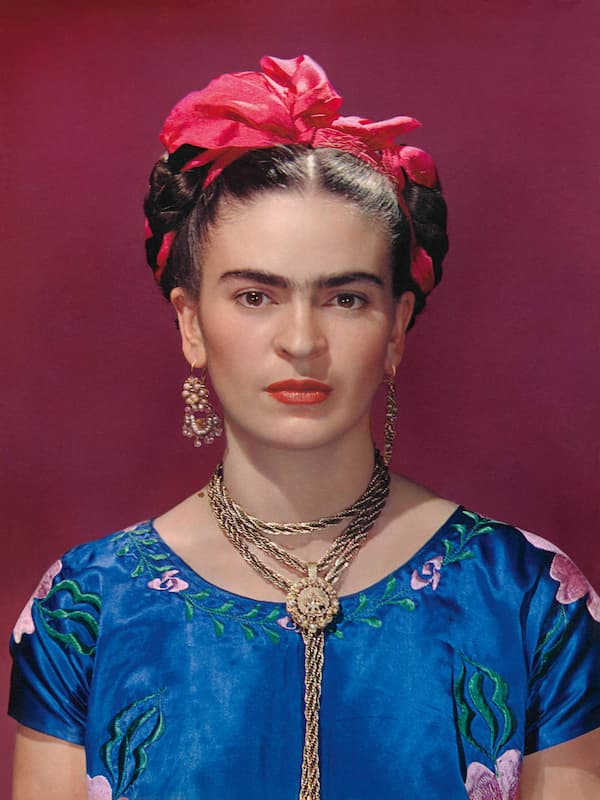

Nickolas Muray: Frieda Kahlo, 1939 (Nickolas Muray Photo Archives)

Of mixed German and Mexican parentage, Kahlo was headed for medical school until a bus accident at age 18 changed her life forever. Suffering for the next 30 years from the chronic pain that was a result of the accident, she made this a focus of her art. She had had an interest in art as a child and resumed her work in the field, working from her bed.

She met the artist Diego Rivera through their common interest in Communism. They spent the late 1920s travelling through Mexico and the US and married in 1929. She divorced him in 1939 and remarried him the following year, both being involved in different affairs during their marriage. Unsuccessful operations on her back, an amputated leg, recurring infections, and her constant pain drove her to commit suicide at age 47.

The Italian guitarist and composer Simone Iannarelli (b. 1970) wrote his suite, Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo, for guitar duo based on seven paintings by Kahlo. He sees it, much like Mussorgsky did, as a promenade around an exhibition.

The composer writes:

This work for two guitars, in the form of a suite, is a promenade over seven iconic pictures of the famous Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Each piece tries to recreate the images, atmosphere, inside feelings or background of these works of Frida. Sometimes these are more descriptive, as in Unos cuantos piquetitos (‘A Few Small Nips’) and Mi nacimiento (‘My Birth’), through the use of special guitar effects to catch the inner suffering of the artist, or, as in Las dos Fridas (‘The Two Fridas’), use imitative (canon) style. Other times, they are more oneiric (surrealistic), as in Lo que vi en el agua (‘What I Saw in the Water’), or El sueño (‘The Dream’), using harmonies borrowed from Impressionism

The first painting, variously titled Lo que vi en el agua (What I Saw in the Water) or What the Water Gave Me (Lo que el agua me dio) from 1938, has been called a biographic painting. Only her toes and her thighs appear in this self-portrait, while roots, plants, flowers, corpses, insects, birds and people she knew float and are reflected. What is in the water includes the Empire State Building in New York shooting out of a Mexican volcano, a skeleton resting on a hill, a faceless man strangling a woman, a floating naked female figure, and various forms from nature.

Kahlo: Lo que vi en el agua (What I Saw in the Water), 1938

(Paris: Collection Daniel Filipacchi)

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 1. Lo que vi en el agua (What I Saw in the Water) (ChromaDuo)

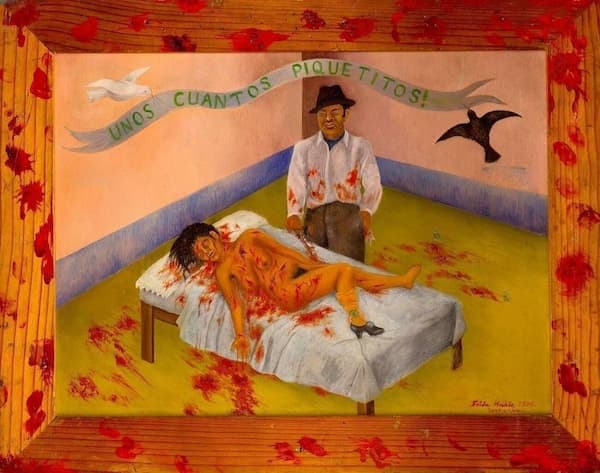

Unos cuantos piquetitos comes from a report in the paper about a man who murdered his girlfriend, stabbing her over and over again. Confronted about his crime, the murderer said in court, “But I just gave her a couple of little nips!’. Kahlo’s painting says otherwise; the police report said 20 stab wounds. The woman’s body is turned in two different directions and is still partially clothed in a single high-heeled shoe, an extravagant trim strap, and a fallen stocking. Aside from the brilliant colour of the blood, the painting is done in incongruous pastels. The pillowcase is elaborately trimmed. Two pigeons, one dark and one light, hold the title banner. Blood is everywhere – on the bed, the floor, his shirt and hands, and even on the frame of the painting.

Kahlo: Unos cuantos piquetitos (A Few Small Nips), 1935 (Mexico City: Museo Dolores Olmedo)

In the music, the sound turns violent, with guitar slaps and an urgent tempo.

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 2. Unos cuantos piquetitos (A Few Small Nips) (ChromaDuo)

Completed in 1939 after her divorce from Diego Rivera, Las dos Fridas (The Two Fridas), shows the two Fridas, one on the left in a traditional Tehuana costume, with a broken heart, and the other in modern dress. The clouds behind are stormy and seem to reflect her feelings of ‘desperation and loneliness with the separation from Diego’.

Kahlo: Las dos Fridas (The Two Fridas), 1939 (Mexico City: Museo de Arte Moderno,)

In his music, Iannarelli gives us a sympathetic and emotional portrait of Kahlo’s feelings – release from the past and the promise of the future, tempered with regret. The movement seems to end on a question. He uses canon to show the two women.

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 3. Las dos Fridas (The Two Fridas) (ChromaDuo)

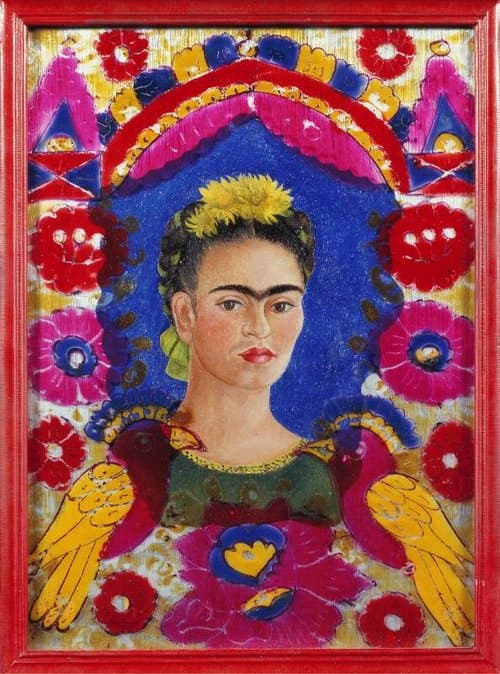

One of her most famous pictures is a self-portrait done in 1938. The glass frame, already decorated, was purchased in a village market. She added her own portrait, done on a sheet of aluminium. The frame, exuberantly painted in bright colours with birds (a traditional motif in Mexican folk imagery), sets off her image, which looks uncompromising. The style is not unlike a religious icon.

Kahlo: Autoretrato, “El Marco” (Self-Portrait, The Frame), 1938 (Paris: Musée National d’Art Moderne)

The picture was shown in Paris in January 1939 as part of a collective exhibition entitled Mexico organised by the surrealist André Breton. This picture was sold to the Louvre and was her first sale to a high-profile collection.

Iannelli’s music seems to take us into a dream state, with a plucked melody seemingly formed out of the air to become a lyrical statement against an arpeggiated background.

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 4. Autoretrato, “El Marco” (Self-Portrait, “The Frame”) (ChromaDuo)

Sleep, death, life and dreams all come together in Kahlo’s 1940 painting, El sueño (La cama) (The Dream (The Bed)). In the bed, Kahlo sleeps, intertwined in ivy. It creeps up from the foot of the bed to cover her. Above her, on the canopy, lies a skeleton; its lower body has a similar tangle, but these are explosives, not ivy. The skeleton holds a bouquet and is much larger than the figure in the bed. The dreams come out in the cloud background.

Kahlo: El sueño (La cama) (The Dream (The Bed)), 1940 (New York: Collection of Selma and Nesuhi Ertegun)

The music for The Dream is repetitive, reflecting reality and its dream world. Time passes in ticks of an invisible clock, or is that the tick of the bombs?

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 5. El sueño (The Dream) (ChromaDuo)

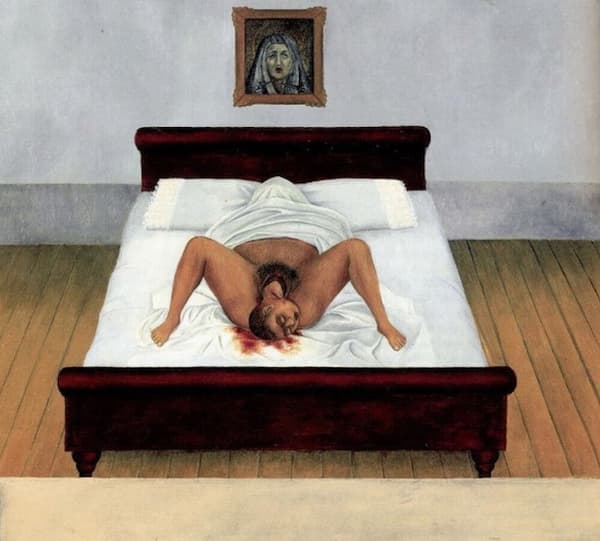

Her 1932 painting on metal, Mi nacimiento (My Birth), shows the fully formed Frida emerging from her mother’s womb with a full head of hair and prominent eyebrows. A sheet covers the mother’s face, so she is left anonymous but may refer to her own mother, María Ysabel González Garduño, who died the same year as this painting. Or, in a more pragmatic way, the only parent to the completed Frida Kahlo was Kahlo herself. Above the bed is a traditional weeping ‘Virgin of Sorrows’, but all she can do is look on and weep, but not provide any actual help.

This was the first painting done by Kahlo with the support of her husband, who encouraged her in a project to paint her ‘major life events’.

Kahlo: Mi nacimiento (My Birth), 1932 (New York: Collection of Madonna)

The violent actions of the two guitarists underscore the bloody imagery of the birth on a white bed.

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 6. Mi nacimiento (My Birth) (ChromaDuo)

The last painting Iannarelli chooses is the 1949 work El abrazo de amor de el universo, la tierra (México), yo, Diego, y el Señor Xolotl (The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl). As their relationship matured, Kahlo found herself dealing with Diego Rivera more as her child than her husband. In her journal, she wrote, ‘At every moment he is my child, my child born every moment, diary, from myself’. His sexual transgressions hurt her less if she could think of him as other than her husband.

Here, she holds the baby Diego, representing the child she could never bear. Below Diego is her itzcuintli dog, Xolotl, curled up for sleep. She is in the lap of Mother Earth (Mexico), which in turn is held by the Universe. A bloody gash cuts across the neck and torso of the innocently pictured Kahlo, who calmly sits with tears on her face and a stream of milk from her chest. Diego is shown with wide eyes as befitted a painter of ‘spaces and multitudes’, and on his forehead is the third eye of ‘Oriental wisdom’.

They are surrounded by the plants and flowers of Mexico, the roots slipping through the hands of Mother Earth and the Universe.

Kahlo: El abrazo de amor de el universo, la tierra (México), yo, Diego, y el Señor Xolotl (The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl), 1949 (Mexico City: Collection of Jacques & Natasha Gelman)

The music, after the tumult of the last movement, seems to have settled into a peaceful declaration of love – the love of a person and the love of the world around.

Simone Iannarelli: Siete pinturas de Frida Kahlo – No. 7. El abrazo de amor de el universo (The Love Embrace of the Universe) (ChromaDuo)

Simone Iannarelli

Kahlo’s pictures take us to a violent and painful world. Her decision to bring her autobiographical details to the fore in her work made her different from nearly every other artist in the world, both in her time and following. Simone Iannarelli’s music brings out deeper elements in the art and gives us the opportunity to both look at and hear Kahlo’s emotional response to her situation(s).

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter