Gyórgy Sebök

My first mentors were my parents both of who were musicians. Despite resisting their influence, as any child would, I couldn’t help the fact that their ways of working, analyzing, and applying themselves seeped into my consciousness.

I remember countless Saturday mornings when I’d pull the covers over my head to drown out my mother’s crooning. As her young students struggled with their pieces, I’d hear, “One and DA, two and DA.” I’d fume and angrily wonder if this was a singing lesson or a piano lesson.

My father, who was a member of the Toronto Symphony cello section for thirty-eight years, practiced many hours with a metronome to maintain a steady beat, and slowly, under tempo, painstakingly, he went over and over the difficult segments to learn them precisely.

When I showed some aptitude, my first piano teacher was carefully chosen. I adored Mrs. Silver. She passed on to me her fine sense of style, her finesse, her disciplined approach to rhythm and her innate musicality all in a warm encouraging way — so important for young students. Mrs. Silver was a proponent of good, relaxed hand position and posture, of learning a piece hands separately — first the right hand alone, then the left, before putting them together. We worked carefully reinforcing effective practice habits, isolating tough passages — all invaluable lessons and applicable later on as I began my cello lessons.

By that point — at the tender age of twelve — I had already learned good taste in my musical approach. This was also due to the fact that my parents exposed me to all types of musical experiences. My dad rehearsed chamber music in our living room. They took me to concerts and I was lucky enough to hear every notable artist who came to town — Jacqueline du Pré, Mstislav Rostropovich, Yehudi Menuhin, Arthur Rubinstein, Vladimir Horowitz, and my father’s teacher Zoltán Kodály. My dad took me to dress rehearsals of many operas when he played in the pit for the Canadian Opera Company. We had recordings playing on the radio on all the time. When one is studying music it is so important to go to concerts and hear how it should be done!

Janos Starker, Gyórgy Sebök and Josef Gingold

Sebök was Starker’s dear friend and piano partner for 60 years. In Starker’s view Sebök was “one of the greatest teachers of all time.” Sebök arrived in Bloomington, with Starker’s help in 1962 without any English but he picked up the language, he joked, by watching television talk show host Johnny Carson. Sebök was a diminutive, elegant man with a thick accent and a gigantic intellect, who always held a cigarette in a long ebony holder. We students flocked to his master classes for his inspiring word of wisdom.

Sebök, like Starker, had an amazing ability to discern exactly what should be said to a student and how. His advice was psychologically probing, full of anecdotes, poetically evocative and he always referenced the historical context. He deftly revealed wisdoms and illustrations to allow the student to figure out for themselves how to move forward. Sometimes the comments had a Zen-like quality to them.

I remember a student once who abruptly launched into the Beethoven Piano Concerto in C Minor even before he had sat down or so it seemed. Sebök stopped him abruptly. He insisted that the first note of a piece must convey everything — the tone, mood, character, and even tempo of the piece. Sebök then demonstrated. Much to our amazement and delight, Sebök played only the first note of a piano work and we could guess which piece he was playing. Then he did it again with another piece and again. It was uncanny!

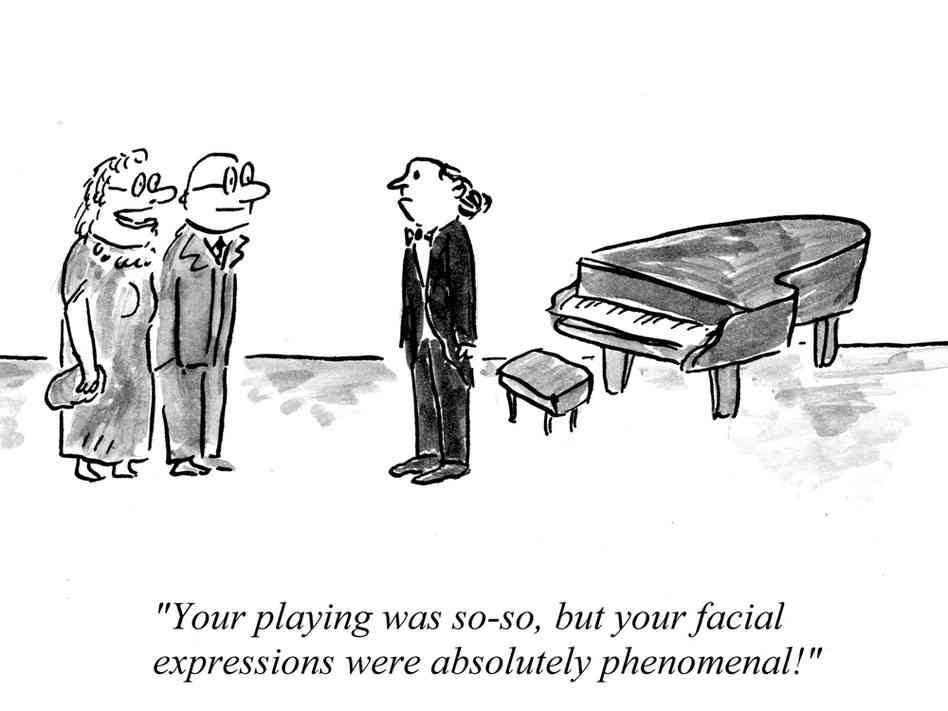

Another class a young lady performed. When she ended her piece she shook her head unhappily. Sebök asked, “Did you dislike how you played, or did you dislike how you felt?” There followed a discussion about how we should gauge what we have conveyed to the audience. Despite nerves and accompanying jitters, heart palpitations, nausea and sweaty palms at a certain level our music making can supersede these private symptoms and move and entertain the audience. We performers must guard against negative facial expressions and body language so as not to detract from the audience’s experience.

Sebök made us think deeply as a result of his challenging remarks. When I performed the Brahms Sonata for Cello and Piano in F Major for him in preparation for a competition, Sebök listened critically. After I completed the work, he leaned back. Slowly he crossed his arms. He sat silently for what seemed like an eternity as his eyes bored into me.

“You play with your will,” he said. I was flummoxed! Was this a criticism or a compliment? It took several weeks of honest self-evaluation to ferret out what he meant. Those five words changed my playing forever. I finally realized that I was forcing the musical shape rather than allowing it to flow naturally — I was willing the music to a certain way rather than liberating it.

Great teachers and mentors give us a valuable gift — the skill to be our own teachers, the ability to listen critically and objectively and the impetus to pass on this priceless oral tradition so we can become musical mentors ourselves.

Bach – BWV 564

Chopin Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35