In the caricatures of James Gillray (1756–1815) in the early years of the 19th century, the soprano Mrs. Billington figures large.

James Gillray started working as an apprentice to a lettering engraver and in 1778, was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools to study engraving under the training of Francesco Bartolozzi. By the 1780s, he was a caricaturist and was regarded as using a coarseness and viciousness new to his day. His caricatures of the royal family, in particular King George III and the Prince Regent, were shocking to foreigners. At the same time, the texts in his art refer to Milton, Shakespeare, Homer, Horace, and show a thorough knowledge of popular song and stage (including opera) culture.

His depiction of Napoleon as ‘Little Boney’ did more to denigrate the leader of the French armies than any military defeat. At 1.68m, 5’6”, Napoleon was taller than the average Frenchman (1.60m) and the same height as most of his soldiers (1.65–1.69m). In this detail of a Gillray print, we have King George III peering through his glass at ‘Little Boney’, and this is how he was always shown – in miniature with a big hat.

Gillray: The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver (detail), 16 June 1803 (Metropolitan Museum)

The English soprano Elizabeth Billington (1765–1818) started her career as a child pianist but, by the time of her death, was described as ‘the most celebrated vocal performer that England ever produced.’ She performed with her parents (her mother was a singer and her father an oboist) and initially started her stage career as an accompanist for her mother. By age 10, she was on stage as a singer herself. Her 9-year-old brother was her orchestra conductor and continued in this role for many of her later opera appearances. She made her first London appearance in February 1786 and was an instant success. A scandal in 1792 drove her to the continent, starting in Naples, where she learned Italian opera. From 1801, she was back in London, and her services were hotly contested between Drury Lane and Covent Garden, resulting in an agreement where she sang at both theatres. Starting in 1803, she did 4 seasons of Italian opera at the King’s Theatre, retiring from the stage in 1806. She was praised by The Harmonicon for ‘‘inexhaustible fund of ornaments, always elegant, always varying, always extemporaneous’ and they noted that she never wrote down her ornaments. They also noted that later in her career, her weight ‘deprived her of elegance and even ease of motion.’

Gillray, as a satirist, picks up on her foibles and exaggerates them.

In this image from December 1801, she’s shown singing the role of Madane in Arne’s Artaxerxes. One action she was frequently criticized for was her ‘inelegant’ attitude ‘of pressing her hands against her bosom in passages that require exertion’. Gillray shows her in this attitude.

Thomas Augustine Arne: Artaxerxes (completed by I. Page and D. Druce) – Act I Scene 14: Air: Fly, soft ideas, fly (Elizabeth Watts, Mandane; The Mozartists; Ian Page, cond.)

Gillray: A Bravura Air: Mandane, December 1801 (British Museum)

Mrs. Billington is shown in her role of Clara in La Duenna, an opera by the father and son team of Thomas and Thomas Linley (to a text by Richard Brindley Sheridan). Clara would be one of her signature roles in London.

Mrs. Billington has her distinctive feathers – we will see these in other images. Her dress was trimmed with pearls and had a ‘vandyked’ trimming, showing she was supposed to be Spanish. You can see how the caricature is virtually a reversed image of Mandane above.

Gillray: Clara – a Bravura, 4 January 1802 (British Museum)

Thomas Linley: The Duenna, Act II – When a Tender Maid (Louise Toppin, soprano; John B.O’Brien, piano)

A week later, she was shown in a fight with the Prince Regent’s mistress, Mrs. Fitzherbert. In yellow trousers, the Prince of Wales is in a ‘jazey’ wig that simulates real hair, declaring, quoting an air from The Beggar’s Opera: ‘How Happy could I be with either \ Was t’other dear Charmer away’. Mrs. Billington (in red) has had her face scratched by the claws of Mrs. Fitzherbert (in light blue). Mrs. Billington here is in the role of Clara and we recognize her feathers.

Gillray: A new bravura with a duett affettuoso, 12 January 1802 (British Museum)

John Gay: The Beggar’s Opera: Act II – Shall I not claim my own? … How happy could I be with either (Ann Murray, Polly Peacham; Philip Langridge, Captain Macheath; Yvonne Kenny, Lucy Lockit; Aldeburgh Festival Orchestra; Steuart Bedford, cond.)

Four days later, in a third caricature from January 1802, she was shown as having ‘lost her notes’. Sheridan, on the left, will pay anything to get her voice back and holds a moneybag to prove it. W.T. Lewis, Deputy Manager of Covent Garden, is feeding her spoonfuls of golden guineas, saying he has every hope for a speedy recovery. The putti at the side carry her note that says, in part, ‘Dear Sir, It grieves me to the heart that I am not able to play this evening – my Throat being so closed as not to leave me a single Note in my Voice’.

Billington, fought over by the managers of Drury Lane and Covent Garden, settled by agreeing to sing alternately at each house at a salary of 3,000 guineas for the season and a benefit (where she would take the ticket sales). Her salary would have the purchasing power of £320,000 today.

Gillray: Theatrical doctors recovering Clara’s notes!, 16 January 1802

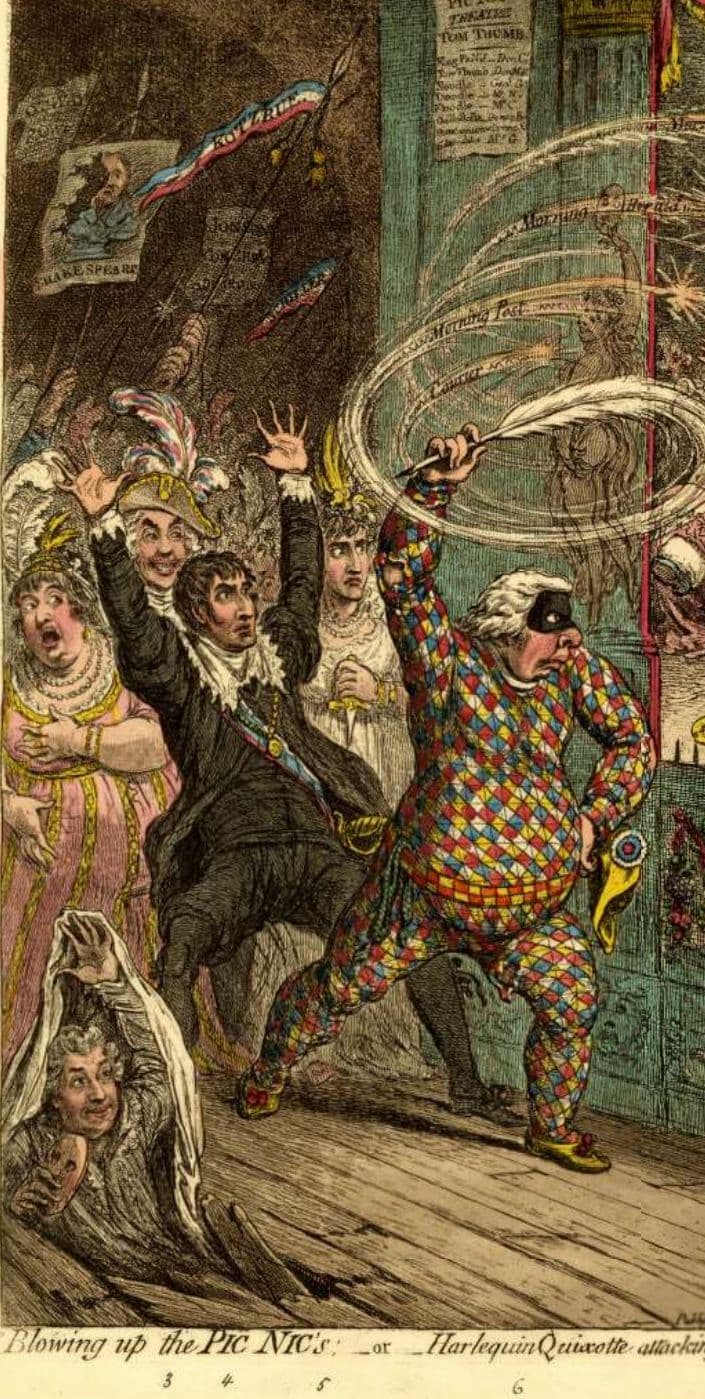

Mrs. Billington, shown in the same pose as her Mandane caricature above, appears in the background of a caricature showing Sheridan attacking the amateur theatricals of the Pic Nic Society. Sheridan is dressed as Harlequin (albeit with a ripped costume) with an empty purse hanging from his belt. He’s followed by the actor John Kemble, in his Hamlet costume, with his arms raised, a characteristic attitude. Behind Kemble is Mrs. Billington, also shown in a characteristic pose. The ghost of David Garrick, mask in hand, comes up through the floor in the bottom left corner.

Gillray: Blowing up the Pic Nic’s; -or- Harlequin Quixotte attacking the puppets. Vide Tottenham Street pantomime (detail), 2 April 1802 (British Museum)

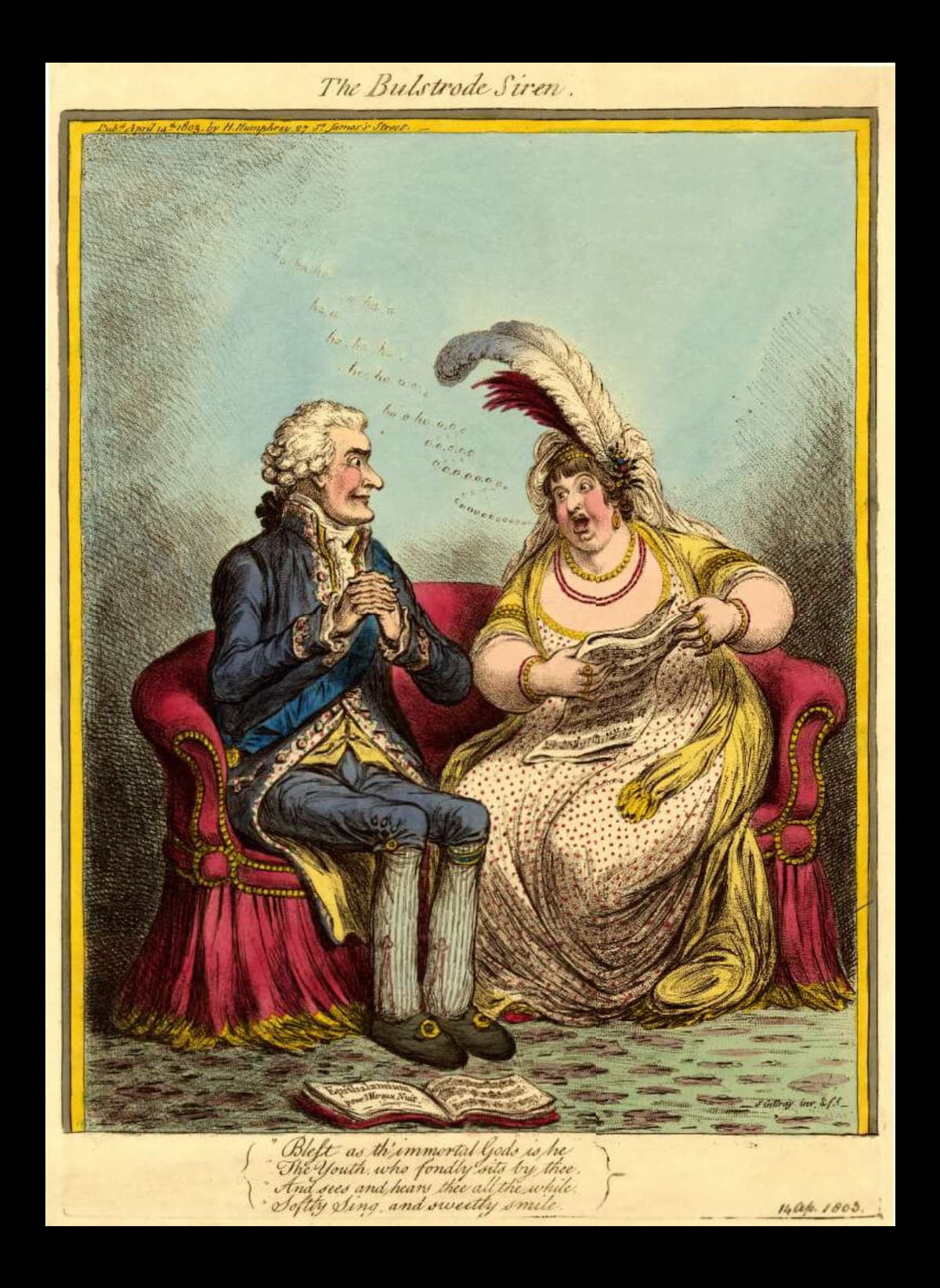

In April 1803, Mrs. Billington visited Bulstrode, the country house of the Duke of Portland. He was rumoured to have paid her very lavishly for her appearance. In this caricature, he’s shown in profile, wearing an old-fashioned court suit and wearing his Ribbon as Knight of the Garter. He’s thin, but his engorged legs and feet indicate he has gout. She’s dressed as we’ve seen her before, with her fathers and a décolleté gown. She may hold her music, but she’s looking alluringly at him. The music book at his feet is entitled (in bad French) ‘Epithalamium pour l’Hereux Nuit’ (Epithalamium for the Happy Night). An Epithalamium is a poem written for a bride on her wedding night.

Gillray: The Bulstrode Siren, 14 April 1803 (British Museum)

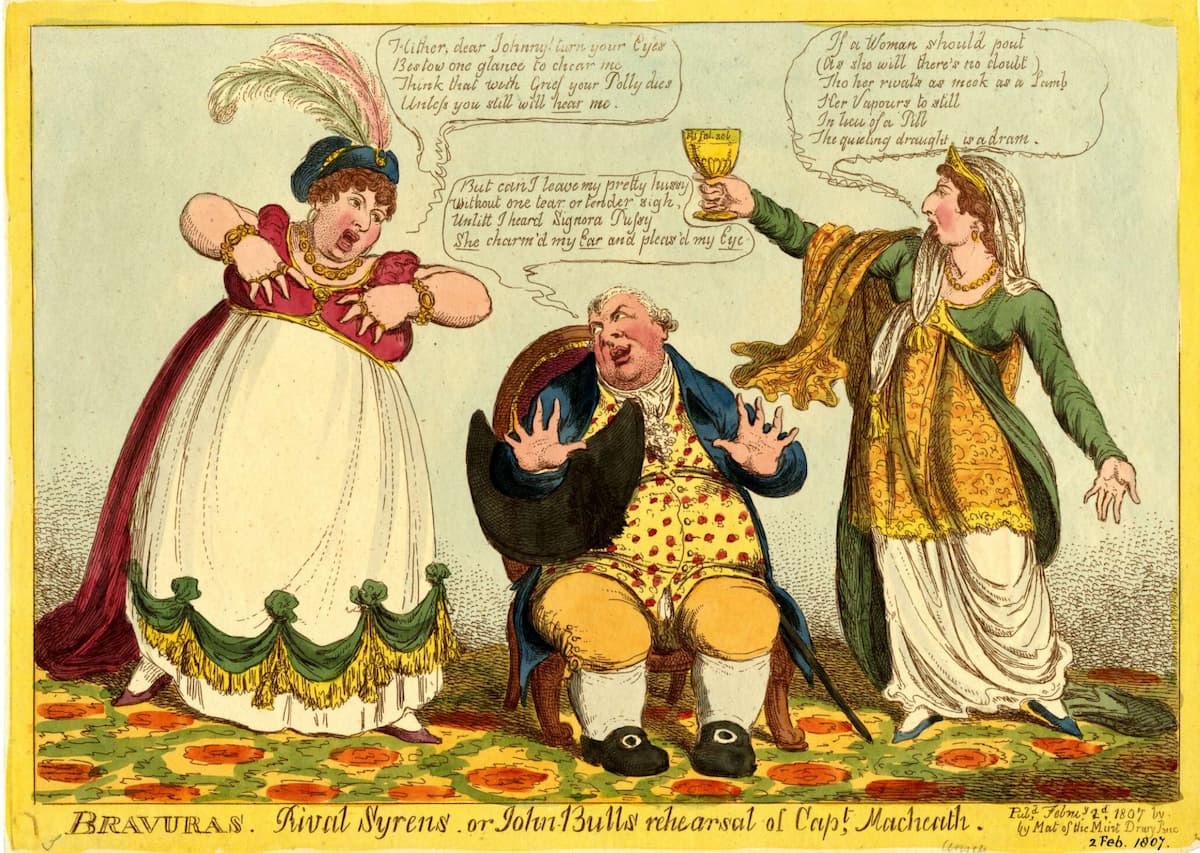

One last caricature from 1807 shows Mrs. Billington and her newly arrived rival, Angelica Catalani (1780–1849). Catalani arrived in London just as Mrs. Billington was retiring from the stage. Mrs. Billington is in the role of Polly, singing lines adapted from her song ‘Hither dear husband’ from The Beggar’s Opera. Catalani, who was as famed for her slim figure and Billington was for her size, sings lines adapted from ‘When A Wife’s in a Pout’. John Bull, in the middle, sings a song in the role of Captain Macheath.

Gillray: Bravuras. Rival syrens– or John-Bulls rehearsal of Capt Macheath. 2 February 1807 (British Museum)

John Gay: The Beggar’s Opera: Act III – What do I see! Oh! Macheath again in custody! … Hither, Dear Husband, turn your eyes (Polly, Lucy, Macheath) (Ann Murray, Polly Peacham; Philip Langridge, Captain Macheath; Yvonne Kenny, Lucy Lockit; Aldeburgh Festival Orchestra; Steuart Bedford, cond.)

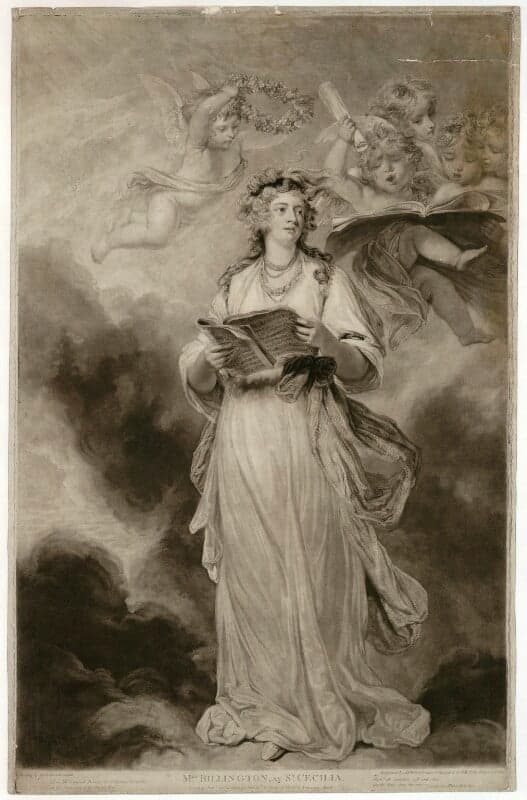

Just as much as Gillray’s Napoleon caricatures defined him forever as a little man in a big hat, when, in fact, he was just an average size and taller than most, his caricatures of Mrs. Billington remove any idea of subtlety. In his art, she’s a fat woman with limited gestures. In the brush of Sir Joshua Reynolds, however, showing her as St. Cecilia, the patron saint of music, she has a much more sublime appearance.

James Ward, after Sir Joshua Reynolds: Elizabeth Billington, mezzo tint, published 1803

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter