When he was thirty-one years old, Ludwig van Beethoven cracked.

In a touristy town just outside of Vienna, he sat down and wrote arguably the most famous letter in classical music history.

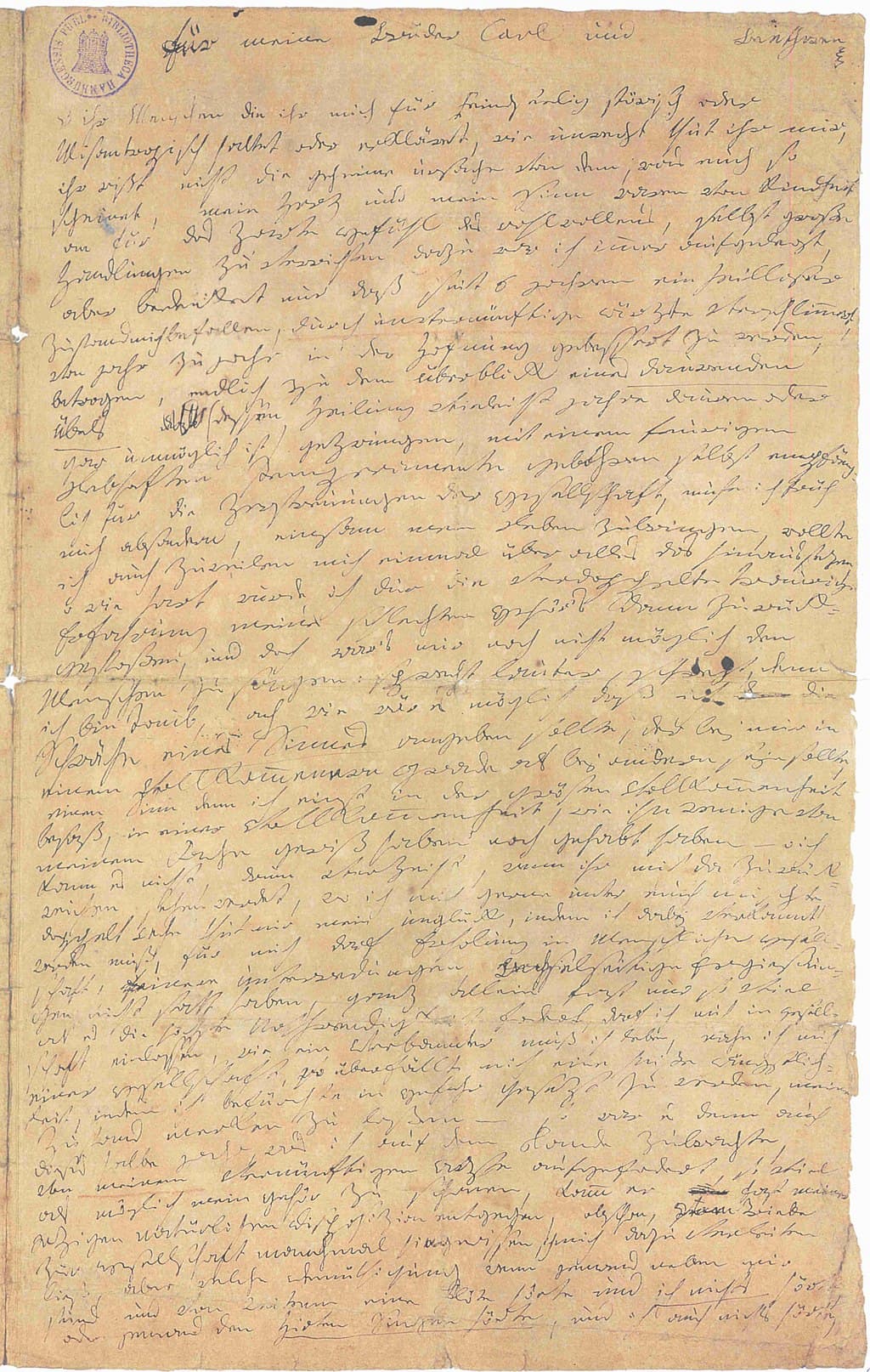

Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament

It was a cry from the depths of his soul, a confession about the extent of his physical and mental health issues, and a quasi-legal document akin to a will.

Today we’re looking at the story of Beethoven’s famous Heiligenstadt Testament, and five of the most heartbreaking quotes from it.

Origins of the Heiligenstadt Testament

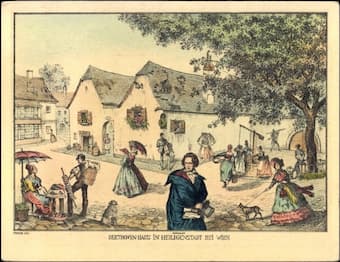

In the spring of 1802, Beethoven’s health worsened. His doctor advised him to avoid stress and to spend some time away from Vienna. So in April 1802, he traveled to the idyllic village of Heiligenstadt.

Unfortunately, the rest and relaxation didn’t help. In fact, without distractions, his mental health rapidly got worse.

He began writing the document on 6 October 1802 and continued on 10 October. It expresses his devastation at his deafness and his desire to die by suicide.

The Intended Recipients of the Heiligenstadt Testament

The Testament was addressed to his brothers Karl and Johann.

Ludwig had a complicated relationship with both brothers.

Karl had moved to Vienna in 1794. He worked several jobs, one of them being as a liaison between Ludwig and music publishers. But he came across as arrogant. Also, Ludwig had never introduced him to publishers, so they were bewildered by the sudden letters written in the royal “we.” At one point Karl promised some piano sonatas to one publisher while Ludwig had promised them to another, and they had a fight about it that supposedly turned physical.

András Schiff Beethoven Piano Sonata No.15 ‘Pastorale’ Op.28

Karl’s name appears throughout the document, but Johann’s doesn’t. Historians don’t agree about what this means. It could have been something as practical as Ludwig feeling unsure about which of Johann’s names to use on a quasi-legal document (his full name was Nikolaus Johann van Beethoven), to repulsion at having to write the name “Johann” at all, since that was the name of their abusive, alcoholic father.

Beethoven, 1803

Five Heiligenstadt Testament Lines and What They Say About Beethoven

1. “O ye men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do ye wrong me”

In the opening passage of the Testament, Beethoven bemoans the reputation he had as a prickly antisocial curmudgeon.

He writes that he has always been naturally inclined to goodwill and generosity, but that the devastation brought about by his health troubles has soured his whole temperament.

He lays special blame at the feet of doctors, claiming they “cheated” him for years by dangling the hope of improvement in front of him – a hope that, by 1802, he believed had always been empty.

2. “It was impossible for me to say to men speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.”

Beethoven was devastated by his deafness, of course, but something that seems to have bothered him just as much or even more was what his deafness would mean for his social position and his ability to support himself.

He expresses frustration at how he never has felt able to tell the truth about the extent of his disability, for fear that it would impact his musical reputation: “Ah how could I possibly admit such an infirmity in the one sense which should have been more perfect in me than in others[?]”

Postcard of Beethoven in Heiligenstadt

3. “What a humiliation when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing and again I heard nothing, such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life.”

Beethoven’s doctor had encouraged him to seek rest and relaxation by going to the countryside, but here we see how such treatment didn’t address the core source of Beethoven’s debilitating stress. In fact, it’s easy to see why giving Beethoven time to mull would make it even worse.

Emmanuel Pahud, Daishin Kashimoto, Lawrence Power Perform Beethoven’s Serenade op. 25

4. “Ah it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce, and so I endured this wretched existence”

Many people believe the romantic myth that Beethoven loved composing so much that it gave him the strength to keep on living.

The Heiligenstadt Testament suggests a somewhat darker possibility: he felt an obligation to his talent. That obligation, rather than his sheer love of music alone, was a major factor in keeping him from acting on his suicidal thoughts.

5. “It is so long since real joy echoed in my heart – O when – O when, O Divine One – shall I find it again in the temple of nature and of men – Never? no – O that would be too hard.”

This passage was written on 10 October. Over the course of the week, Beethoven clearly had time to stew in his emotions, and he reached a new pitch of emotion by the end of the Testament. His sentences have gone from long and relatively objective to being just sheer outbursts of pain, with many dashes and desperate half-formed thoughts.

This letter must have meant something profound to Beethoven. Even through his countless moves he kept it.

It was discovered by his friends Anton Schindler and Stephan von Breuning after his death. They published it a few months later.

Beethoven String Quartet Op. 135 in F Major – Ariel Quartet

Conclusion

The Heiligenstadt Testament – and Beethoven’s deafness more generally – is often condensed into an oversimplified narrative of “Beethoven bravely overcame his deafness.”

Although Beethoven was indeed brave, it’s also important to remember that his life and career post-Testament were never, ever easy.

One way or another, he never stopped pleading for understanding from the world around him.

There’s nothing we can do for Beethoven now, besides keeping his music in our lives. But perhaps we can honor his fighting spirit by honoring and supporting other living musicians struggling with mental or physical health issues themselves.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Been there emotionally, I think I know how he felt. Friends have told me I have a duty to go on with my multiple creativity especially in the arts & sciences – music + maths in particular, & like the Beetles, I get by with some help from my friends. BUT at least I have not become anti – social, & grief @ my she-friend being banished by the home office & her breakdown is something friends & creativity will help me to exist with. One day I may even live again !