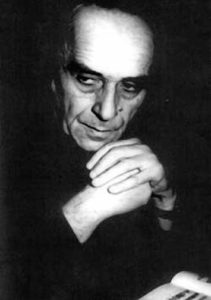

Sulkhan Tsintsadze

Georgian composer Sulkhan Tsintsadze (1925–1991) started his music studies in Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, studying the cello with a private tutor and then continued onto the Tbilisi State Conservatory. He completed his studies in Moscow at the Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory. While still a student, in 1950 he was awarded the USSR Government Prize for two works for string quartet.

He returned to Tbilisi to teach at the State Conservatory in 1963 and headed the school as rector from 1965-1984. As a composer, he preferred writing works for specific performers and so his 24 Preludes for Piano of 1971 was written for the Georgian pianist Roman Gorelashvili.

Anything with a title of 24 Preludes has to have at least an idea of Bach’s 24 Preludes and Fugues in the background, but it’s actually Mozart’s pupil, Johann Nepomuk Hummel who comes to mind here. Hummel was the first to write a set of 24 preludes (1815) without pairing them, as Bach did, with a following fugue. Hummel’s model was followed by Chopin (1835-39), Alkan (1847), Busoni (1881), Rachmaninoff (1892-1910), Scriabin (1893-95), Kabalevsky (1943-44), Shostakovich (1950-51), continuing up to Shuwn Zhang (2011-12). Tsintsadze arranged his 24 Preludes around the circle of fifths, with one prelude in each relative major/minor key: C-a-G-e-D-b-A, etc.

The works are used by Tsintsadze to combine 20th century ‘classical’ with the various characteristics of Georgian folk music – variously exploiting its rhythmic, melodic, harmonic, and modal characters.

Looking at the first Prelude, in C major, Tsintsadze sets up a definitive and striking melody in the left hand. We can immediately hear the non-European sound of the music.

Tsintsadze: 24 Preludes for Piano: No. 1 in C major (Inga Fiolia, piano)

By the last Prelude, this bass melody makes its final, and definitive statement.

Tsintsadze: 24 Preludes for Piano: No. 24 in D minor (Inga Fiolia, piano)

Inga Fiolia

Other tracks take traditional songs and dances as their basis. “Tsintsadze gave new life to traditional songs and dances, such as the austere Svanetian ritual chanting; the colourful Pshavian motet; the Gurian krimanchuli, the upper voice singing tradition with elaborate ornamentation; the Khorumi, a war dance with an unrelenting rhythm in quintuple metre; and to the sounds of national drum and pipe instruments, such as doli and chiboni.”

Listen to the driving rhythm of the Prelude in E major and, at the same time, think what Bach did with his prelude in the same key.

Tsintsadze: 24 Preludes for Piano: No. 9 in E major (Inga Fiolia, piano)

Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I: 24 Preludes and Fugues: No. 9 in E Major, BWV 854 (Jenő Jandó, piano)

That contrast says more about the change in the idea and function of the prelude than any words.

The performer, German-Georgian pianist Inga Fiolia, like Tsintsadze, studied at the Central Music School of the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow. Her repertoire extends from the Baroque to the 21st century, giving her a unique insight into Tsintsadze’s position in the piano repertoire.