Carl Nielsen’s second symphony bears a curious title: The Four Temperaments. The temperaments, or the four bodily humours, were the four liquid elements that make up the human body: ‘yellow bile, phlegm, black bile and blood, a preponderance of any one of which will give rise to a character that is choleric, phlegmatic, melancholic or sanguine’. When you’re out of humour, one of the humours will predominate and your character will change with it.

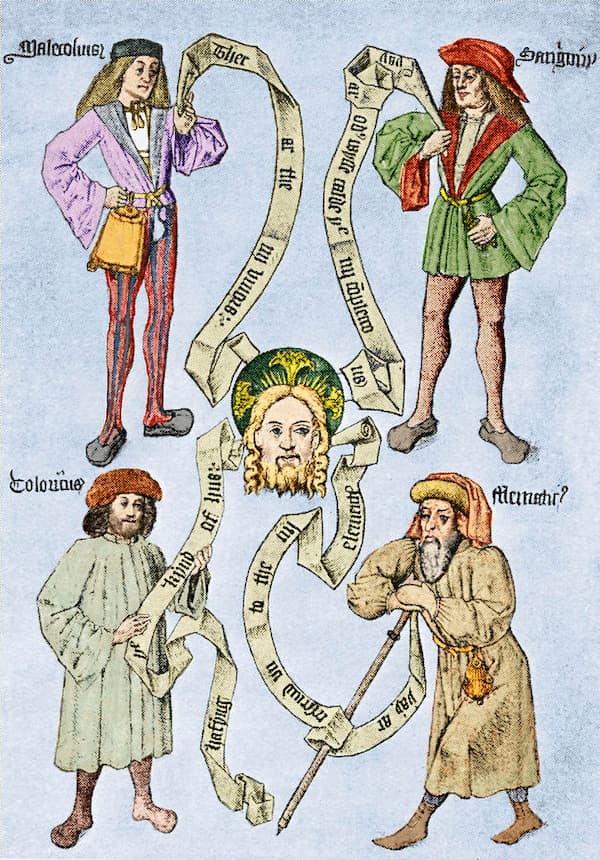

The Four Humours from The Guild Book of the Barber-Surgeons of York, ca 1486

Nielsen saw a primitive painting in a country inn depicting the four humours and used it as the inspiration for his second symphony. In the image above, the head of Christ is surrounded by personifications of the humours. From the upper left: black bile (Melancholic, upper left), blood (Sanguine man, upper right), phlegm (Phlegmatic, lower right) and yellow bile (Choleric, lower left). These were the principal determiners of one’s health, both physical and mental, and also were part of one’s personality.

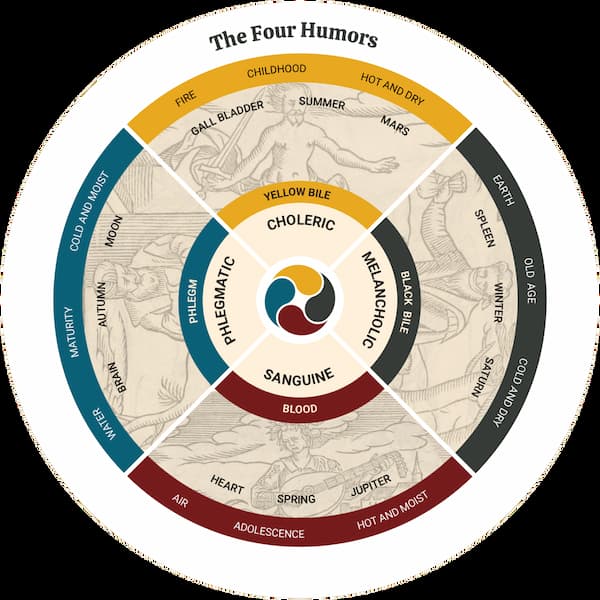

Four humours chart adapted from Thomas Walkington’s Optick Glasse of Humors, 1639

The study of the humours, or humourism, started with ancient Egyptian medicine but wasn’t formalised until the ancient Greeks. Humour refers to one’s inner fluids, or, in a tree analogy, one’s ‘sap’. Hippocrates applied the idea to medicine and the four bodily fluids. Hippocrates and then Galen suggested that the balance or imbalance of the fluids produced behavioural patterns. Humouralism, or the doctrine of the four temperaments, started with Galen (129—216 AD) and didn’t fall out of favour until the 17th century. Microbial theory and chemistry drove out the four humours.

The four temperaments were determined by the balance of hot and cold/moist and dry. The temperaments, or what we might call personality, came down to a question of temperature: the result of the action of cold, hot, wet, and dry in governing behaviour.

The work opens with the appropriately named Allegro collerico. An excess of the hot, dry emotion of choler, or yellow bile, produced an angry disposition. We have a movement that is forthright, expressive, impetuous, and interruptive.

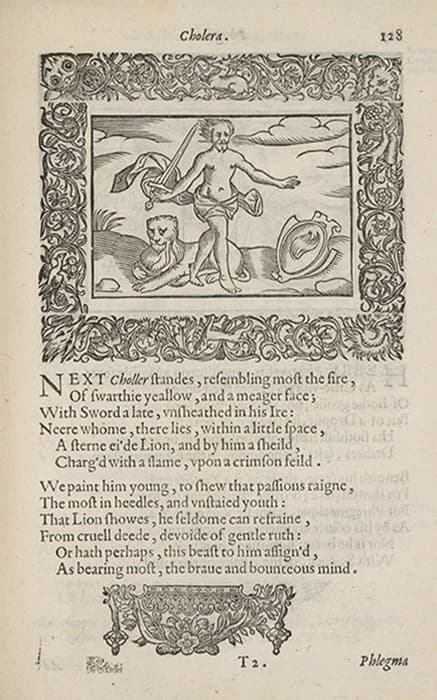

Henry Peacham: Choleric, from Minerva Britanna, 1612 (Folger Shakespeare Library)

Henry Peacham: Choleric, from Minerva Britanna, 1612 (Folger Shakespeare Library)

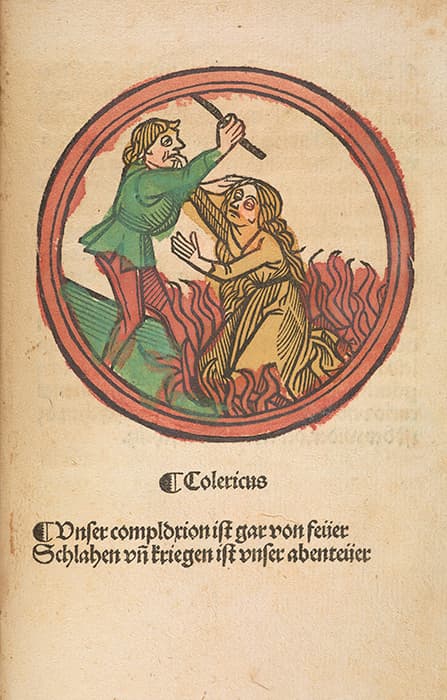

A medieval German woodcut from the Deutsche Kalendar shows a hot dry man who furiously beats a woman kneeling at his feet. In Minerva Britanna from 1612, Choller carries a sword, ‘unsheathed in his Ire’, while surrounded by a lion and a crimson shield with a flame. He’s shown as a young man, passionate, heedless, and ‘unstayed’. The lion indicates his propensity to cruel deeds. The best that can be said of Choller is that he has a brave and bounteous mind.

Carl Nielsen: Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29, “The 4 Temperaments” – I. Allegro collerico (Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Schønwandt, cond.)

Next comes the phlegmatic movement. This slow march contrasts with the first movement and ‘Nielsen explained that he imagined here a young man of seventeen or eighteen, a trial to his teachers, idle in his lessons, but not to be scolded. His nature leads him to the countryside, where birds sing, fish glide through the water and the sun shines, all depicted in a mood remote from energy or strong feeling’.

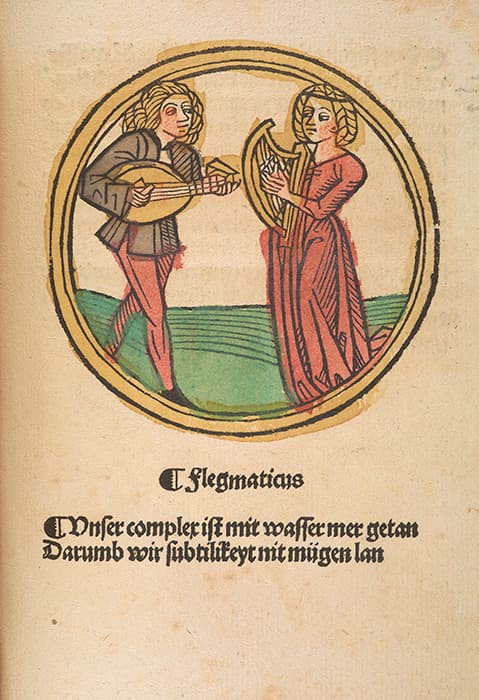

Phlegmatic: Deutsche Kalendar, 1498 (New York Pierpont Morgan Library)

In the Deutsche Kalendar, cold, moist phlegmatic couple prefer retirement and leisure, signified here by music.

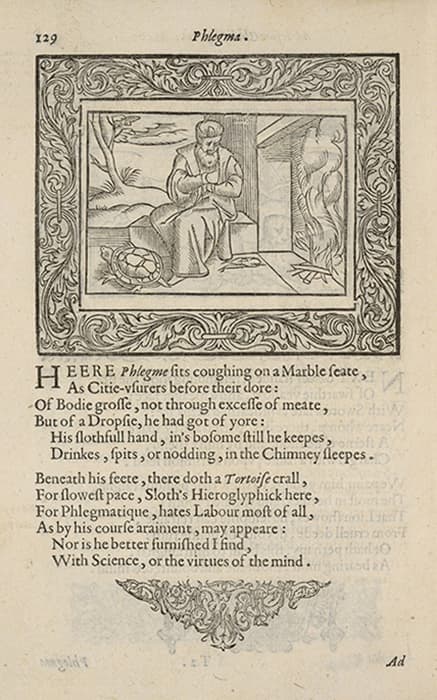

Henry Peacham: Phlegmatic, from Minerva Britanna, 1612 (Folger Shakespeare Library)

Peacham takes a more literal view, with Phlegme sitting coughing next to the fire. He has dropsy, is slothful, and keeps his hand inside his coat. His animal is the tortoise, which, with its slow crawl, emblemises sloth and which hates working. The science of the mind isn’t given a good image.

Carl Nielsen: Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29, “The 4 Temperaments” – II. Allegro comodo e flammatico (Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Schønwandt, cond.)

The melancholic third movement, in a minor key, is a lament, with an oboe melody. The movement ends in calm serenity.

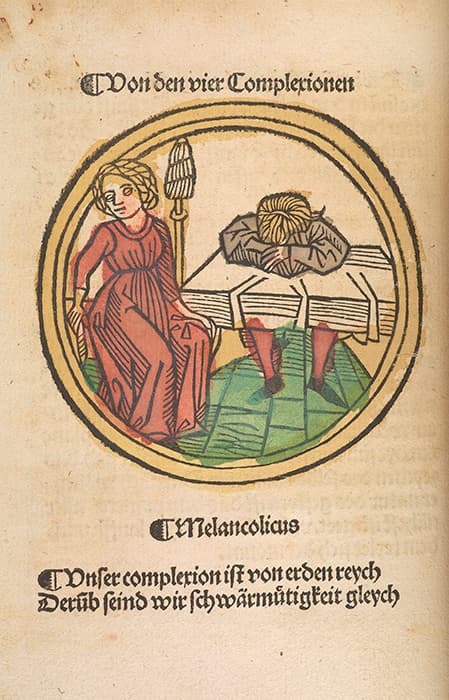

Melancholy: Deutsche Kalendar, 1498 (New York Pierpont Morgan Library)

In the Deutsche Kalendar, melancholy is depicted by an old man with his head resting on a table, since melancholy was associated with old age and scholarship.

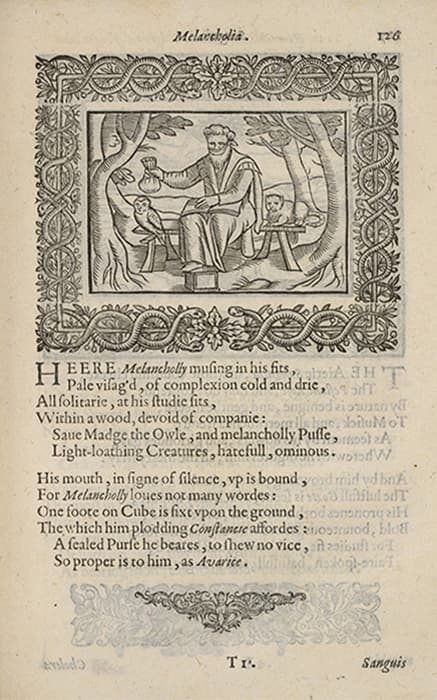

Henry Peacham: Melancholic, from Minerva Britanna, 1612 (Folger Shakespeare Library)

Peacham’s Melancholic sits with bound mouth since he is loath to speak. He is flanked by his owl and cat, creatures Peacham believes to be ‘light-loathing creatures, hatefull and ominous’. He holds a closed purse indicating that he shows no vice, except that of avarice.

Carl Nielsen: Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29, “The 4 Temperaments” – III. Andante malincolico (Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Schønwandt, cond.)

Nielsen used his final movement to show the Sanguine man: one ‘who acts without reflection, thinking the whole world his and that everything will come his way without effort on his part’. Our sanguine and superficial character always believes in the bright side and a positive outcome.

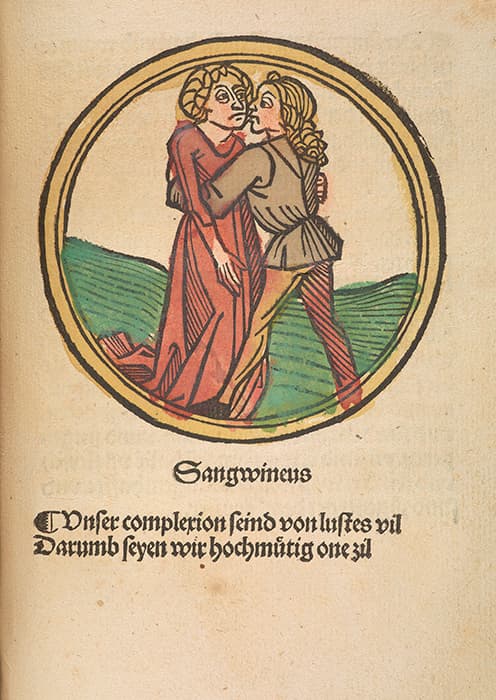

Sanguine: Deutsche Kalendar, 1498 (New York Pierpont Morgan Library)

In the Deutsche Kalendar, the hot, moist man is shown as an active wooer embracing a woman.

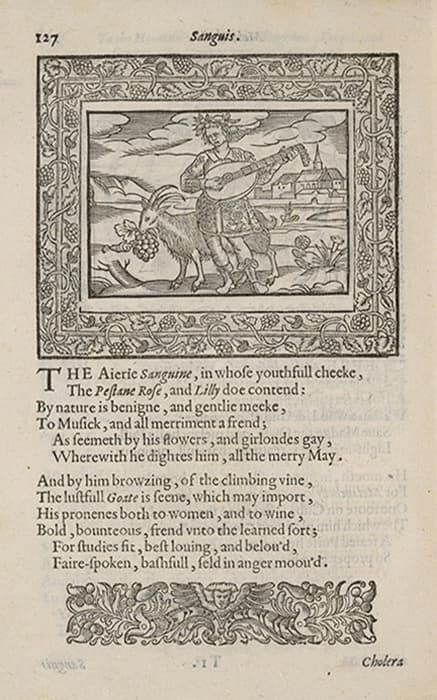

Henry Peacham: Sanguine, from Minerva Britanna, 1612 (Folger Shakespeare Library)

Peacham gives the quality of music to the sanguine character. He carries a rose and lily, depicting his benign and gentle nature. On the other hand, he rides on a lustful goat eating grapes, showing the character’s inclination towards women and wine. Bold, bounteous, friend to all, both loving and beloved, fair-spoken, bashful, and seldom moved to anger.

Carl Nielsen: Symphony No. 2, Op. 16, FS 29, “The 4 Temperaments” – IV. Allegro sanguineo (Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Schønwandt, cond.)

The language of the humours still is part of our daily vocabulary. How often do you note someone who is ‘out of humour’ or who speaks ‘coldly’ or has ‘hot’ replies? Actions can be described as ‘cold-blooded’ and a person can be defined as ‘hot-headed’. All of this comes from the imbalance of the humours and how we perceive them.

Our job, and that of our medieval doctors, is to maintain a level. Too choleric and you’ll soon die of a heart attack or a stroke. Too melancholic and depression has soon claimed you. Too phlegmatic and you will soon sit alone, with only your tortoise for company. Keep your humours in balance and live a much happier life!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter