Leonard Bernstein contributed a modest but significant group of compositions for solo piano. As a noted pianist suggested, “the Bernstein works for solo pianos are a viable addition to present-day keyboard literature, and should not be underestimated.” Among his works for solo piano, we find his “Anniversaries,” a series of piano vignettes that musically portray his friends, family, and colleagues.

Four Anniversaries

“For Felicia Montealegre”

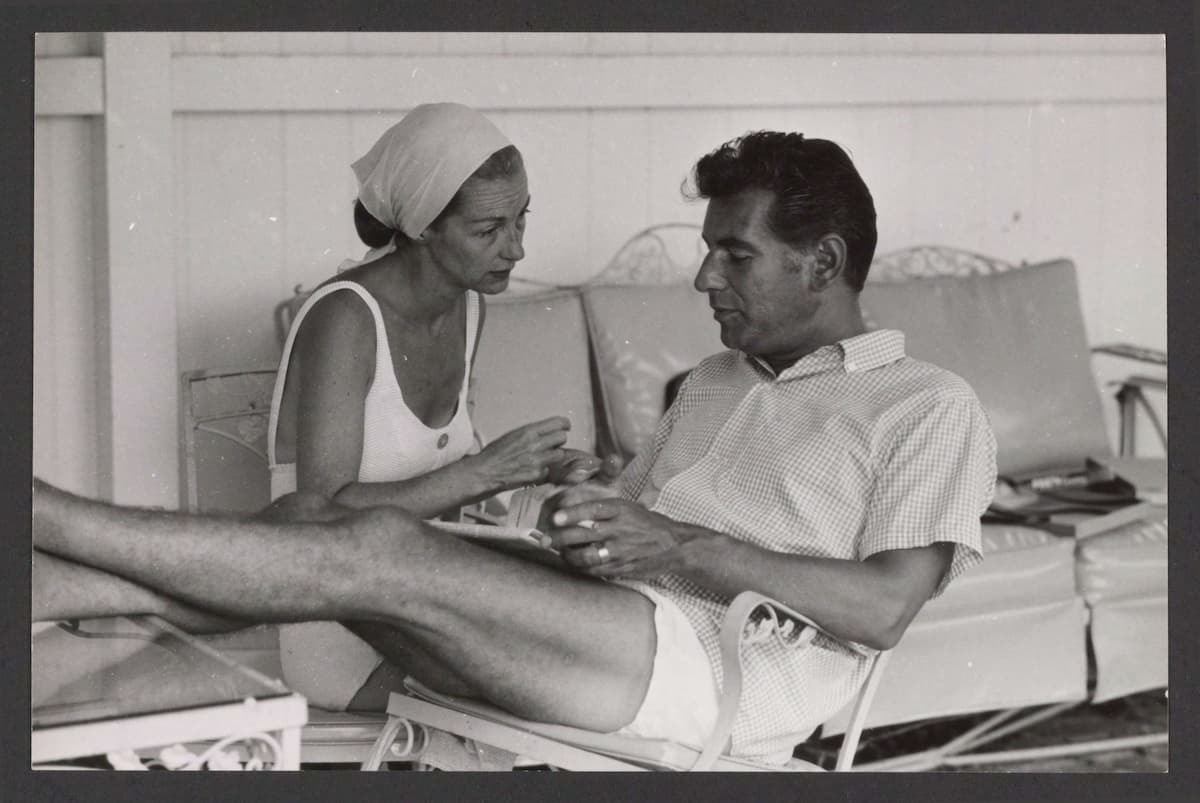

Felicia Montealegre and Leonard Bernstein

The set of Four Anniversaries dates from 1948 and commences with Felicia Montealegre. She was a stunningly beautiful stage and television actress making her living in New York. Leonard Bernstein was the wonder boy of the American classical music scene, who had made his spectacular conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic. They met at a party hosted by pianist Claudio Arrau, with whom Montealegre was studying. They were engaged a few months later, but the engagement was broken off after less than a year. The reason for the break-up of the relationship was not a secret, as Bernstein’s homosexual proclivities were undisputed and well-documented. Felicia nevertheless continued to pursue him over the next three years, and her Anniversary, written during the initial stage of courtship, conveys her charm, composure, and vivacity.

Leonard Bernstein: Four Anniversaries, No. 1 “For Felicia Montealegre” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Johnny Mehegan”

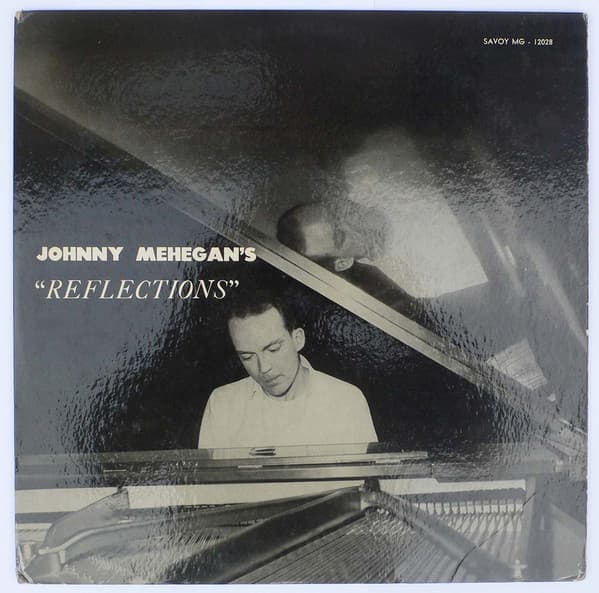

John Mehegan

Bernstein frequently visited a small club in Greenwich Village called “Marie’s Crisis.” That club had hired the services of the jazz pianist John Mehegan, who also held teaching positions at Juilliard and Columbia Teachers College. He also served as jazz critic for the New York Herald Tribune, and one of his recordings was exclusively devoted to tunes by Bernstein. Mehegan was the author of Jazz Improvisations, hailed as “the first definitive text to codify the principles of jazz.” Regarding that publication, Bernstein wrote, “There has long been a need for a sharp, clear, wise textbook which would once and for all codify and delineate that elusive procedure known as jazz improvisation… at last there is a Johnny Mehegan who has the ability to do it. He has that peculiar combination of abilities that is absolutely necessary for such an endeavor: academic and scholarly knowledge (and insight and interest), plus an immense practical knowledge (and insight and interest) born of long years of simply doing it himself and teaching others to do it.” His Anniversary unmistakably relies on jazz elements, with syncopation and a blues note included in the opening musical statement.

Leonard Bernstein: Four Anniversaries, No. 2 “For Johnny Mehegan” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For David Diamond”

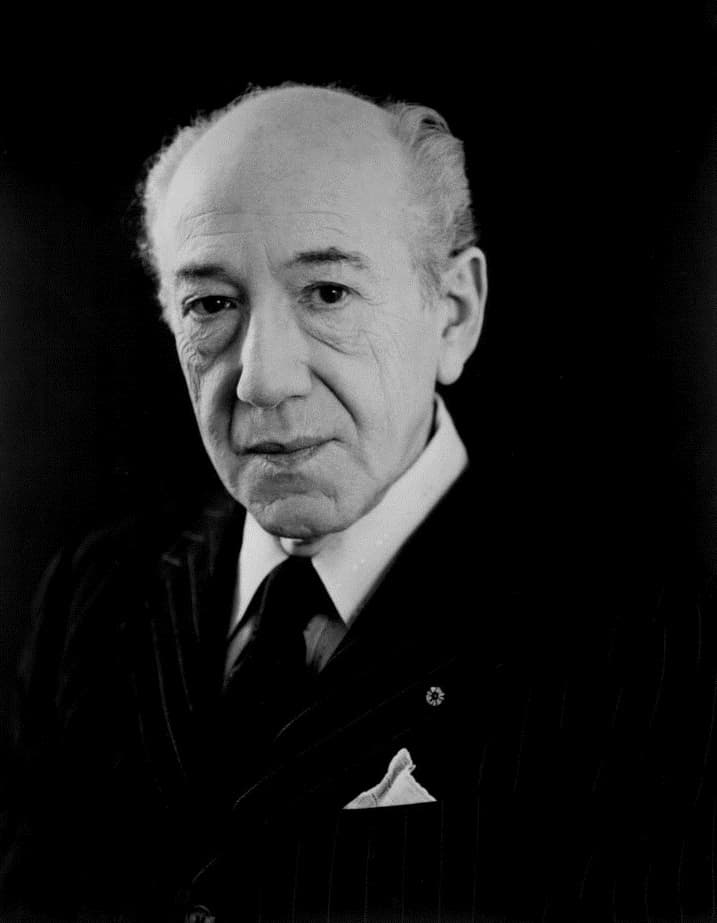

David Diamond, 1987

David Diamond is considered one of the preeminent American composers of his generation. His works are frequently tonal or modally inspired, and his widely spaced harmonies give them a distinctly American tone. At the time of the publication of his Anniversary, he was considered a “friend and confidant.” Bernstein conducted a number of world premieres of Diamond’s compositions, including the Piano Concerto and the Fifth Symphony. In turn, Diamond dedicated a number of works to Bernstein. There was some tension between them, however, as Diamond wrote, “You say I should know you by now, I can hardly agree with that. You never allowed me to, ever. I tried in so many ways to know you better and looked forward to seeing you in NY, but you didn’t come last Spring, came to Tanglewood to see you but got a cold shoulder such as I’ve never known from the person who found me super-super repulsive… You better have said, “David, understand that there can be no physical relationship between us.” Diamond’s compositional style is described as “lyrical, clear of structure, and marked by contrapuntal interest and the increasing use of chromaticism in his later compositions.” It comes as no surprise that Bernstein precisely incorporated these musical features into his “For David Diamond.”

Leonard Bernstein: Four Anniversaries, No. 3 “For David Diamond” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Helen Coates”

At the age of fourteen, Leonard Bernstein began his piano studies with Helen Coates. In 1966, Bernstein spoke at a graduating ceremony at Rockford Illinois, Helen Coates’ hometown. “In honoring Helen Coates, my teacher,” he said, “I mean to honor all teachers in all fields and disciplines; I mean to honor teaching itself, man’s noblest profession, as well as his most underrated and underpaid profession.” Bernstein continued, “for more than thirty years she has been a guide, confidante, helper, and inspiration… As a teacher, she introduced me to discipline, to the most profound meaning of work, to the control and penetration of musical beauty. She also listened to my problems, musical and nonmusical, and gave liberal and sage counsel and comfort. As my secretary and friend and assistant, she is still doing the same.” As a fitting conclusion to the Four Anniversaries, “For Helen Coates” offers both “jocularity and bravura.”

Leonard Bernstein: Four Anniversaries, No. 4 “For Helen Coates” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

Five Anniversaries

Bernstein composed his set of Five Anniversaries between 1949 and 1951. Four of the five pieces subsequently became parts of his Serenade for Violin Solo, Strings, Harp, and Percussion, which premiered in Venice, Italy in 1954. While the quotations of the Anniversaries in the Serenade are easily recognized, the original vignettes once more pay homage to deeply felt personal connections.

“For Elizabeth Rudolf”

“For Elizabeth Rudolf” references the mother of a friend who was studying with him at Tanglewood. According to Bernstein’s teacher Helen Coates, Bernstein visited the Rudolf ranch in Montana, indicating that a close personal bond had been developed. The musical vignette “unfolds with audible reticence as regards its rhythmic and harmonic profile, with maybe a nod to Respighi (albeit as arranger) in its melodic content.”

Leonard Bernstein: Five Anniversaries, No. 1 “For Elizabeth Rudolf” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Lukas Foss”

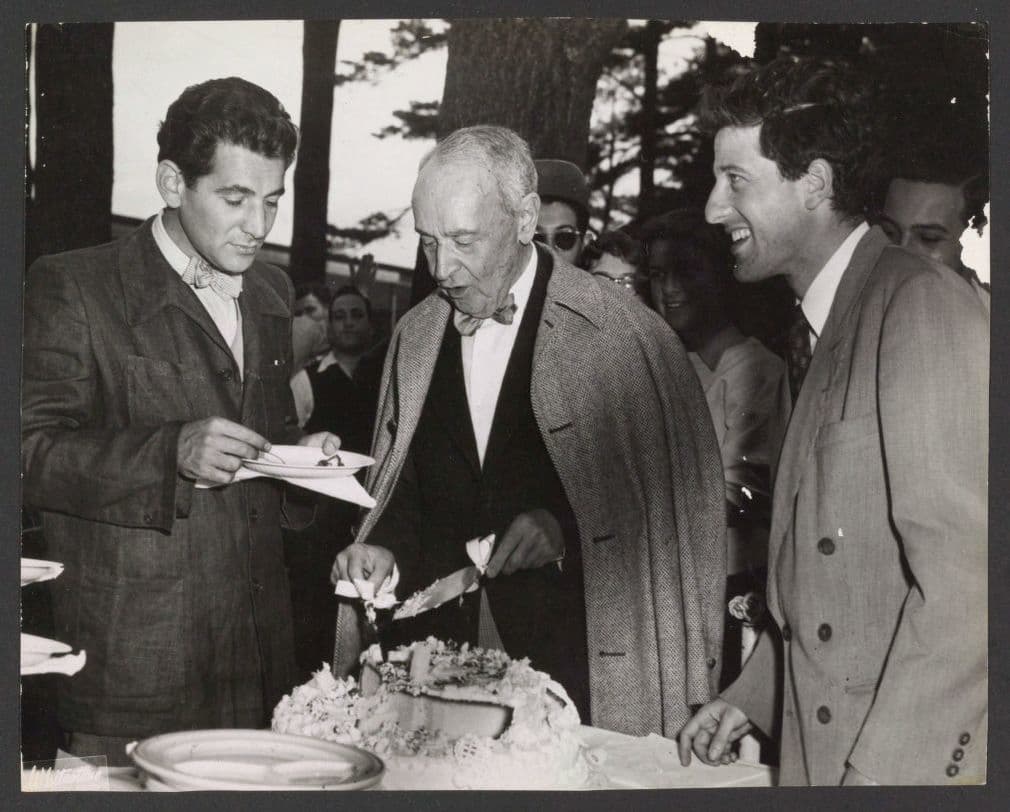

Leonard Bernstein, Koussevitzky and Lukas Foss

Leonard Bernstein and Lukas Foss met in Fritz Reiner’s conducting class at the Curtis Institute. Foss writes, “I was 15 or 16, Lenny was 19 or 20. He was like an older (wiser) brother to me. We’ve been friends ever since.” Both were selected to work with Koussevitzky at the Berkshire Music Center, and they went on to become the “twin prodigies, the fair-haired boys of the contemporary musical scene.” As Foss remembers, “we were his favorite students… he called one of us Dionysian and the other Apollonian, and we were wondering, Lenny and I, which one was which.” Foss continues, “For Koussevitzky, we were like his children, you know. It was more than a friendship.” Foss became a vocal advocate for Bernstein’s artistry and impact on American culture. When Bernstein became a conductor of the New York Philharmonic, Foss wrote, “Now that it is official let me again congratulate you and New York and music in America. All I can say is I shall be much more homesick than ever for New York.” The Foss Anniversary “feels appreciably more equivocal in its intricate figuration that evinces no mean harmonic subtlety as it unfolds.”

Leonard Bernstein: Five Anniversaries, No. 2 “For Lukas Foss” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Elizabeth B. Ehrman”

The third Anniversary in this set is once again dedicated to the mother of one of Bernstein’s roommates at Harvard. Bernstein roomed with Kenneth Ehrman at Eliot House, and Bernstein sought frequent counsel from Kenneth about his struggles with the Harvard music department, which was then quite conservative. He writes to Ehrman, “Tillman Merritt hates me, but Mother loves me. Walter Piston doubts me, but Copland encourages me. I hate the Harvard Music Department. You can quote that…. I hate it because it is stupid & high schoolish and disciplinary and prim and foolish and academic and stolid and fussy.” Yet Bernstein already had a knack for seizing the limelight, which trumped his frustrations. “I’ve graduated with a bang,” he reported in another letter to Ehrman. “An incredible A in the Government course, and a cum laude. A great class day skit which I performed to a roaring crowd through a mike, and got in some parting cracks… at the old school and its officials.” The vignette inscribed to Elisabeth B. Ehrmann is a delightful study of jazz idioms.

Leonard Bernstein: Five Anniversaries, No. 3 “For Elizabeth B. Ehrman” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Sandy Gellhorn”

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway

Sandy Gellhorn was the adopted son of writer Martha Gellhorn, an American novelist, short story writer, journalist, playwright, and essayist. Critics write, “Stylistically as well as thematically, her fiction shows strong evidence of years spent as a war correspondent. Gellhorn’s skillfully crafted, frequently reportorial prose, is often compared for its hard-edged clarity to that of her late ex-husband, Ernest Hemingway.” Martha Gellhorn was a close friend of the Bernstein family, and as newlyweds, Bernstein and his wife Felicia visited a resort in Mexico, recommended by Gellhorn. This fourth musical miniature was originally dedicated to Martha, but Bernstein subsequently changed the dedication to her son. It is the most forward-looking in its “exploitation of the upper range of the piano’s compass and methodical deployment of its motifs.”

Leonard Bernstein: Five Anniversaries, No. 4 “For Sandy Gellhorn” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)

“For Susanna Kyle”

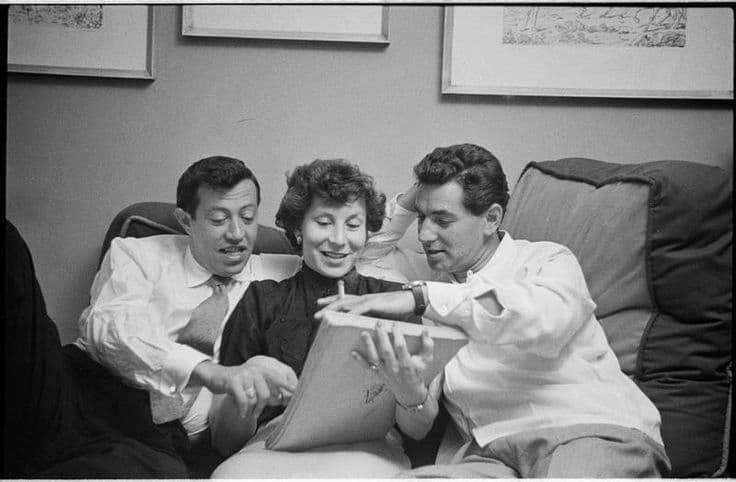

Adolph Green, Betty Comden and Leonard Bernstein

The American lyricist, playwright, and screenwriter Betty Comden contributed to countless Hollywood musicals and Broadway shows in the mid-20th century. Her writing partnership with Adolph Green spanned six decades, and represents “the longest-running creative partnership in theatre history.” Comden and Green met in 1938, and together with the young Judy Holliday and Leonard Bernstein they formed a troupe called the “Revuers.” They performed at the Village Vanguard, a club in Greenwich Village, and in 1944 collaborated on the book and the lyrics to Bernstein’s “On the Town.” Betty Comden married Steven Kyle in 1942, and their daughter Susanna Kyle was born in 1949. The closing piece “For Susanna Kyle” celebrates the birth of Comden’s daughter and makes “for a conclusion of great poise that most resembles a lullaby in its rapt inwardness.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Leonard Bernstein: Five Anniversaries, No. 5 “For Susanna Kyle” (Benyamin Nuss, piano)