In the world of classical music, John Marsh (1752-1828) is not really a household name, but he probably should be. He was one of the most prolific composers in 18th-century England, producing roughly 350 mostly instrumental works. Although very little of his music was actually published during his lifetime, we have a pretty clear picture of his life and works. You see, Marsh kept an extensive diary in thirty-seven volumes entitled “The History of My Private Life,” which was discovered and eventually published in 1998.

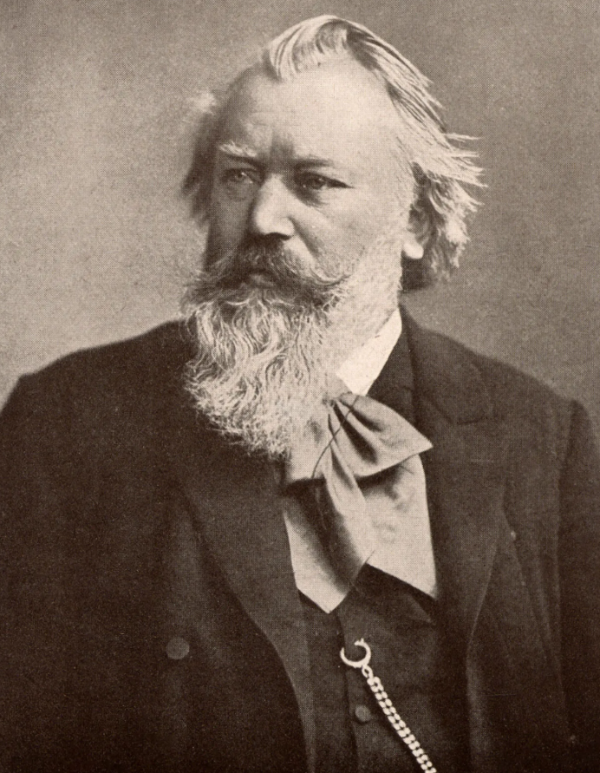

John Marsh

The first twenty-two volumes of “The John Marsh Journals: The Life and Times of a Gentleman Composer (1752–1828)” detail his life up to his fiftieth birthday, and the remaining volumes are an “Account of my Musical Compositions & Publications to this time.” The diaries list thirty-nine symphonies, a “Military Symphony” for wind band, twelve string quartets, three concertos, including one for two French horns, twelve concertos “in the ancient style,” eight sonatinas for keyboard, organ music, including over sixty voluntaries, anthems, hymns, chants and psalm settings, and over forty glees and songs. All that has survived in print, however, are “just nine symphonies, three finales for orchestra and one string quartet. All that remains in manuscript is a handful of glees.”

John Marsh: Conversation Symphony for 2 Orchestras, “Allegro maestoso” (London Mozart Players; Matthias Bamert, cond.)

John Marsh

John Marsh hailed from Dorking, Surrey, and although he showed musical aptitude at an early stage, his father was determined that John should follow in his footsteps and focus on a naval career. Once the family had moved to Gosport, near Portsmouth, John was trained to become a solicitor, and he simultaneously took an active part in the local music scene by performing the violin in concerts. “He taught himself to play the spinet, viola (which became a particular favourite), cello, oboe and organ… and composed his first works for a series of subscription concerts he founded in town.” Following his marriage in 1774, he moved to the cathedral town of Salisbury, “where he met personalities such as Carl Stamitz and the violinist Wilhelm Cramer.” Highly active in the musical community, Marsh established his name as a composer, and a number of his symphonies sounded at subscription concerts and “at the annual Salisbury Festival.” When Marsh inherited a substantial estate in Kent in 1783, he discontinued his solicitor practice and essentially moved to Canterbury. It has been reported that Marsh “was immediately offered the directorship of the ailing Canterbury Concert, which he set about reorganizing with characteristic energy, soon transforming the Concert into a successful organization.” The Marsh family eventually moved to Chichester in 1787, and John once again revived the local music scene. Marsh remained an active participant in concert life before officially retiring in 1813. During the last “15 years, he traveled extensively, and managed to take in one or more of the provincial music festivals.”

John Marsh: Conversation Symphony for 2 Orchestras, “Andante” (London Mozart Players; Matthias Bamert, cond.)

The John Marsh Journals

Judging from this brief biographical sketch, John Marsh had a lively and active interest in music throughout his long life. However, as it has been pointed out, music was not his only pursuit. “He was a man of extraordinarily diversified interests, ranging from astronomy (on which he wrote two published books) and campanology to a part-time military career as an officer in the sometimes unruly Chichester Volunteers during the Napoleonic Wars. In addition to Marsh’s extensive writings on music, his published articles address such topics as religious philosophy and geometry. His writings on musical topics cover a wide range of subjects and reveal an unusually balanced and sensible approach to arguments such as the relative merits of ‘ancient’ and ‘modern’ compositions.” It has even been suggested that Marsh, dissatisfied with “the prevailing low standards of cathedral music, laid the foundations for the reform of Anglican psalm chanting.” His “Conservation Symphony, for two Orchestras upon a new Plan” dates from 1778 and was published in 1784 under the anagram “Sharm.” We do know that it received twenty-two performances in the composer’s lifetime, but what is the advertised “New Plan?” Actually, it is rather a unique idea as Marsh divides the single orchestra into the upper and lower parts. The first orchestra thus includes 2 oboes, violins 1 and 2, basso 1, while orchestra II consists of 2 horns, violas 1 and 2, basso 2. The musical glue, so to speak, is provided by a continuo group of violoncello and harpsichord, as well as the timpani to reinforce the tutti sections. To my knowledge, this is a unique way of dividing a single orchestra, and it has never been repeated. I let you be the judge, but the musical conversation seems rather pleasant and courteous to me.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

John Marsh: Conversation Symphony for 2 Orchestras, “Allegretto” (London Mozart Players; Matthias Bamert, cond.)