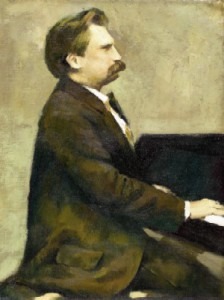

Eugene d’Albert

Eugene d’Albert: Symphony in F major, Op. 4

With his musical career on track—Brahms would remain a staunch supporter—d’Albert managed to find the time to tie the knot no less than 6 times. His second wife, Teresa Carreño was a sensational pianist in her own right. Their union predictably elicited some rather amusing commentaries in the local press, with a Berlin publication reporting, “Yesterday, Mrs. Carreño played for the first time the second piano concerto by her third husband in the fourth Philharmonic concert.” Carreño also dabbled in composition, infusing her pieces with the grace and charm that only the best salon music could offer. Her “little waltz” became and remained one of d’Albert’s favorite encore pieces.

Teresa Carreño: Petite Valse

Busoni

Credit: Wikipedia

Eugen d’Albert: Tiefland (The Lowlands)

Although d’Albert was not well liked as a person, everybody was stunned by his playing. Because of their different ideas about transcribing the music of J. S. Bach for the piano, Ferrucio Busoni absolutely loathed d’Albert. D’Albert, contrary to Busoni only transcribed organ works, pursuing a distinct clarity of texture. Busoni dedicated his most famous Bach transcription—the Chaconne—to d’Albert, who curtly told him that Brahms had already done better. Busoni had considered it impossible to make a piano transcription of the Bach Passacaglia because it contained too much music for one piano and not enough for two. Predictably, he was stunned when d’Albert successfully solved the problem.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Passacaglia BWV 582, arranged Eugen d’Albert

Busoni clearly felt musically and morally superior to d’Albert and could not comprehend that his rival was more successful as an opera composer. In a fit of jealously and rage he referred to his colleague as “d’Alberich,” in reference to the dwarf who jealously guards the treasure of the Nibelungen in Wagner’s Siegfried. All jealousies aside, d’Albert was clearly a remarkable pianist. After hearing a d’Albert performance, the pianist Wilhelm Kempff wrote, “the lion had retracted his paws and now he began to touch the black monster, which he had spent the entire evening on top of, with velvety paws, in such a way that his skin seemed to bristle with pleasure. Yes, from the hairs standing on end of this so tenderly beloved monster, did I not see a flash of green lights as the magician then let the tone of the fading fermata oscillate to create the illusion of a human voice’s perfect vibrato? His hand simply hovered over the mysteriously sparkling black and white keys, like the spirit of God over the water.”

d’Albert plays Chopin Nocturne in B Op 9 No 3 (1905)