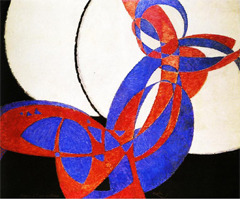

Frantisěk Kupka – Amorpha, Fugue à deux couleurs (1912)

The poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire was the main representative of the modern movement in Paris, where artists such as Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Frantisěk Kupka, Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp met. Apollinaire understood and supported the profound change in the evolution of painting towards abstraction amongst the new generation of painters, which followed the exhibition of Kandinsky’s work in Paris. Now though, the path towards total abstraction continued to evolve in the works of the above-mentioned artists, where color was no longer used just for coloration, but where color became form itself — where the art of pure color becomes pure painting. Kupka’s painting Amorpha, fugue à deux couleurs (Amorpha, fugue in two colors), shown in the Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris in October 1912, is an excellent example — as are the early works of Georgia O’Keeffe. In many abstract works, it is interesting to note that there is often a reference to music (such as in Kupka’s Nocturne). Picabia also used musical analogies to explain his paintings, which for him, like music, touched the purest part of abstract reality. He became the modern movement’s most fervent spokesman. In 1913, he traveled to New York to attend the famous Armory Show, which introduced modern European art to the American public. Picabia appealed to the American people to accept the ‘New Movement in Art’, an appeal which proved to be a complete failure. The general view in America, by critics and public alike, was that these were the works of madmen!

Eric Satie: 3 Morceaux en forme de poire

Georgia O’Keeffe – Music in Pink and Blue No. 1 (1918)

3 Gymnopedies

3 Gnossiennes

Satie also got the attention of the Dadaists, writing many articles for their magazine 391 as well as composing ballets with Picabia. The most famous, the ballet Parade, was composed in 1916-1917 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The script for Parade, written by Jean Cocteau, is that of a ‘parade’ of circus performers trying to attract an audience to an indoor performance. The costumes and sets were designed by Pablo Picasso and by the Italian futurist painter, Giacomo Balla. Satie used ‘ready-made’ Ragtime music, the music of music halls and fairgrounds, adding sounds of a typewriter, foghorn and an assortment of milk bottles — breaking all of the rules of ‘classical’ composition — very much to the consternation of the public and Parisian critics.

Satie’s minimalist, we can say almost ‘abstract’, compositions, in particular his Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, would inspire the avant-garde movement in music in his time, and also generations of modern composers in the 21st century, such as John Cage.