At the Van Cliburn Piano Competition

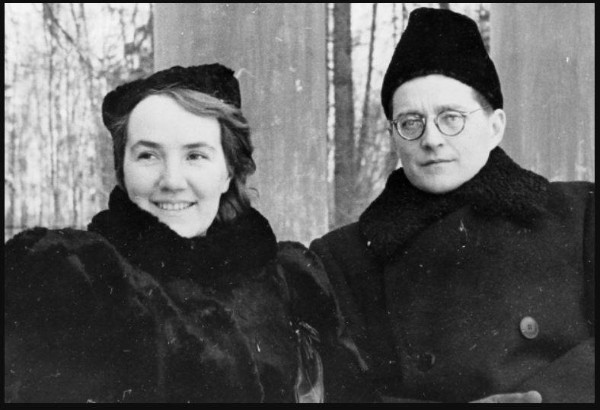

Van Cliburn performing at the Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow

Credit: Tully Potter Collection

The competition began on a sad note. Van Cliburn passed away on February 27th 2013, just before the 14th Van Cliburn Piano Competition began. The first event I attended was a gala dinner where a special tribute was paid to him. A slide show was accompanied by sombre selections from his recordings; the ambiance was mournful; there was not a dry eye in the banquet hall. He was hailed as a “champion of classical music”, whose triumphant win at the Tchaikovsky Piano Competition in 1958 changed the complexion of political relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, at a time when considerable tension existed. He left a legacy as the “hero of the free world”, and through his extraordinary music making, confirmed that music can indeed transcend political, geographic and ethnic boundaries, which validated our belief in the sanctity of the human spirit. That was the first magical moment I encountered.

Van Cliburn 2013

Much had been written and broadcasted in the media about the finalists and the winners. Like all competitions of this calibre, every single competitor would be raved as an outstanding talent in his or her own right. In these three weeks of complete immersion, I had witnessed an array of ultra-impressive technique, incomparable acrobatics, meticulously polished interpretations, intellectual profundity and supreme musicality. However, I must admit, even though many “wowed” me, only a handful “moved” me. After many years of being in the capacity of participating candidate, teacher, adjudicator and audience, I often question the value of these competitions, whether they are crucial or detrimental to one’s artistic growth, and whether the process of “striving to win” distorts the essence of soulful music making. Among the thirty competitors, I have identified the following as the ones who spoke convincingly to me, and truly made a lasting impact:

With Van Cliburn Winner Kholodenko 2013

2) Francois Dumont (France) : I first heard him in the Chopin International Competition in Warsaw in 2010. His playing was naturally stylish, his colours exquisite, and his sounds refined. He was the quintessential French pianist. I admired his interpretation of Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit. However, he did not advance to the semifinals, a disappointing surprise to many. Regardless, I think he already has an international concert career. A Cliburn prize would have just been another feather in his hat.

3) Nikolay Khozyainov (Russia) : I also heard him at the Chopin when he was 17 years old. I found his playing absolutely mesmerizing : crystal clear touch and angelic tones executed with an ethereal and sublime delicacy. His most dramatic moments were captured in Lizst’s Sonata in B minor, in what I would label as “intensity of silences”. Among the most touching on the program were Chopin’s Berceuse in D flat major, op. 57 and Etude in A minor, op.10 # 2. He did not advance to the finals, but he will go places.

4) Kuan-Ting Lin (Taiwan) : This twenty one-year-old pianist studied in Russia since he was fourteen. He was the only pianist who actually moved me to tears, with his expressive but tasteful rendition of the Haydn Sonata in E flat major Hob VXI:52, his melancholy interpretation of Schubert-Lizst’s Gretchen am Spinnrard, and the interplay between forlornness and tempestuousness in his Liszt Annees de pelerinage, Book 1. He manifested a kind of lyrical sorrowfulness coupled with a subtle fiery temperament so rare in one so young. He did not make it beyond the preliminaries. My heart went out to him.

5) Beatrice Rana (Italy) : She was the darling of the competition – poised, charming, vivacious, sophisticated and regal. Moreover, she has the perfect pedigree, born into a family of musicians – from grandparents, parents, to siblings – all playing instruments professionally. Endowed with an elegant flair and innate musicianship, combined with a flamboyant technique, rich sonorous sound quality and an amazing ability to layer her musical lines, she is undoubtedly the consummate artist with all the stars lined up for her to flourish in her concert career. Of course, winning the silver medal at the Van Cliburn further opened all the doors.

My criteria for selecting these favourites were quite simple: They all have to have something meaningful and substantial to say with their music. They have to command my attention in their own compelling way. Last but not least, they have to demonstrate genuine passion for music and humanity, and to master the art of transcending beyond formidable technical prowess, cerebral intellectualism and visceral emotionalism. Until there is a course to teach “magic”, I think we have to contend with the fact that “either you have it or you don’t”.

Alessandro Deljavan:

Francois Dumont:

Nikolay Khozyainov:

Kuan-Ting Lin:

Beatrice Rana: