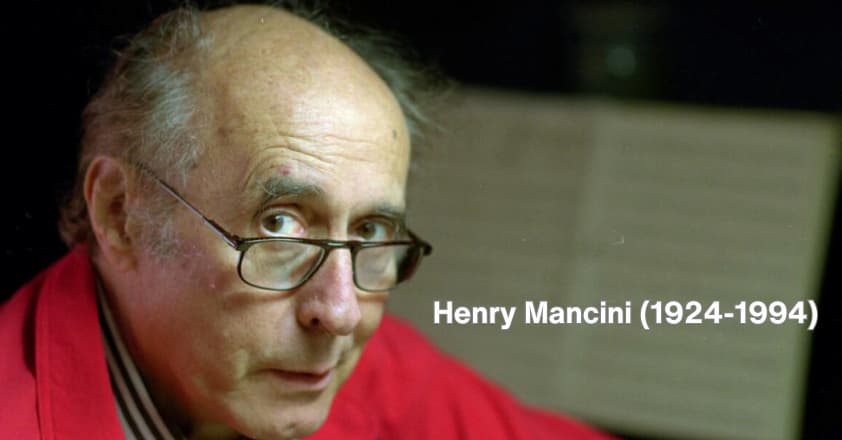

Henry Mancini, one of the greatest composers in the history of film, celebrates his 100th birthday on 16 April 2024. A highly successful recording and concert artist, Mancini was widely successful as a Hollywood composer, making imaginative use of jazz and popular idioms in his pioneering film scores. He is probably best known for his sophisticated theme songs, particularly for such films as “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” “The Days of Wine and Roses,” “Charade,” “Darling Lili” and the unforgettable “Pink Panther.”

Henry Mancini: “Theme Song” The Pink Panther

Allegheny River

Henry Mancini

Enrico Nicola Mancini hailed from Cleveland, Ohio, born to Quinto Mancini and Anna Pece, both with Italian immigrant backgrounds. She was the homemaker and he the breadwinner, and Mancini later remembered, “I never saw my father display a trace of affection for her or me either.” The boy clearly had musical aptitude, encouraged by his father, and he learned the flute and piano as a child. However, the first time he became acutely aware of music was in a local movie theatre in 1935.

Mancini remembered, “First I wondered where the orchestra was sitting, where the sound was coming from. Then I understood that music had been recorded right onto the film already with the voices of the actors and sound effects.” Initially, he thought that there was a big orchestra behind the screen, and he decided on the spot that he wanted to compose like that, to somehow be involved in music for the movies.

Henry Mancini: Rain Drops in Rio (Henry Mancini Orchestra; Henry Mancini, cond.)

Max Adkins

The young Henry Mancini

Quinto Mancini, a worker in the steel mills, decided that his son would become a teacher. He continued to give Henry piano lessons and the boy quickly expanded his musical horizons by secretly teaching himself harmony and orchestration. Day and night he would listen to the radio, becoming gradually aware of the vast musical universe. Mancini produced his first arrangements, and he took formal piano and flute lessons in Pittsburgh. In his spare time, he visited the Stanley Theatre, a performance venue open to traveling vaudeville acts, comics, singers, and animal routines accompanied by a resident pit band.

The pit band of roughly twenty-five players was conducted by Max Adkins, whom Mancini called “the most important influence of my life.” Adkins started Mancini on simple music notation exercises and gradually advanced to studies of the best way to orchestrate for a theatre band. A biographer wrote, “Adkins consistently encouraged acceptance of Mancini’s inexperience and enthusiasm for the big band, and he helped Henry to develop rapidly, with Mancini’s natural feeling for the shape of a melody developing alongside a fluency in orchestration.”

Henry Mancini: Breakfast at Tiffany’s, “Moon River”

Juilliard and Military Bands

In 1942, it was decided that Henry Mancini would attempt to enroll at the Juilliard School. He auditioned with a Beethoven sonata and an improvised fantasy on Cole Porter’s “Night and Day.” He was accepted and received a scholarship, but during his first year was forced to major in piano, as orchestration and composition were not available until the second year. Decidedly unhappy with his academic regime, Mancini enlisted in the military. He went to Atlantic City for basic training and was assigned to the 28th Air Force Band.

Mancini was stationed in France and also provided musical services for units in Germany and Austria. Initially, he was to have been transferred to the Pacific after the war ended in Europe, but since an infantry band needed a good flute, Mancini spent the rest of the war in Nice, in what he called “one of the best periods of my life, ever.” Instead of rejoining Juilliard upon his return, Mancini decided to freelance and he was hired as a pianist and arranger for the Glenn-Miller/Tex Beneke Orchestra.

Henry Mancini: The White Dawn Symphonic Suite (London Symphony Orchestra; Henry Mancini, cond.)

Towards Hollywood

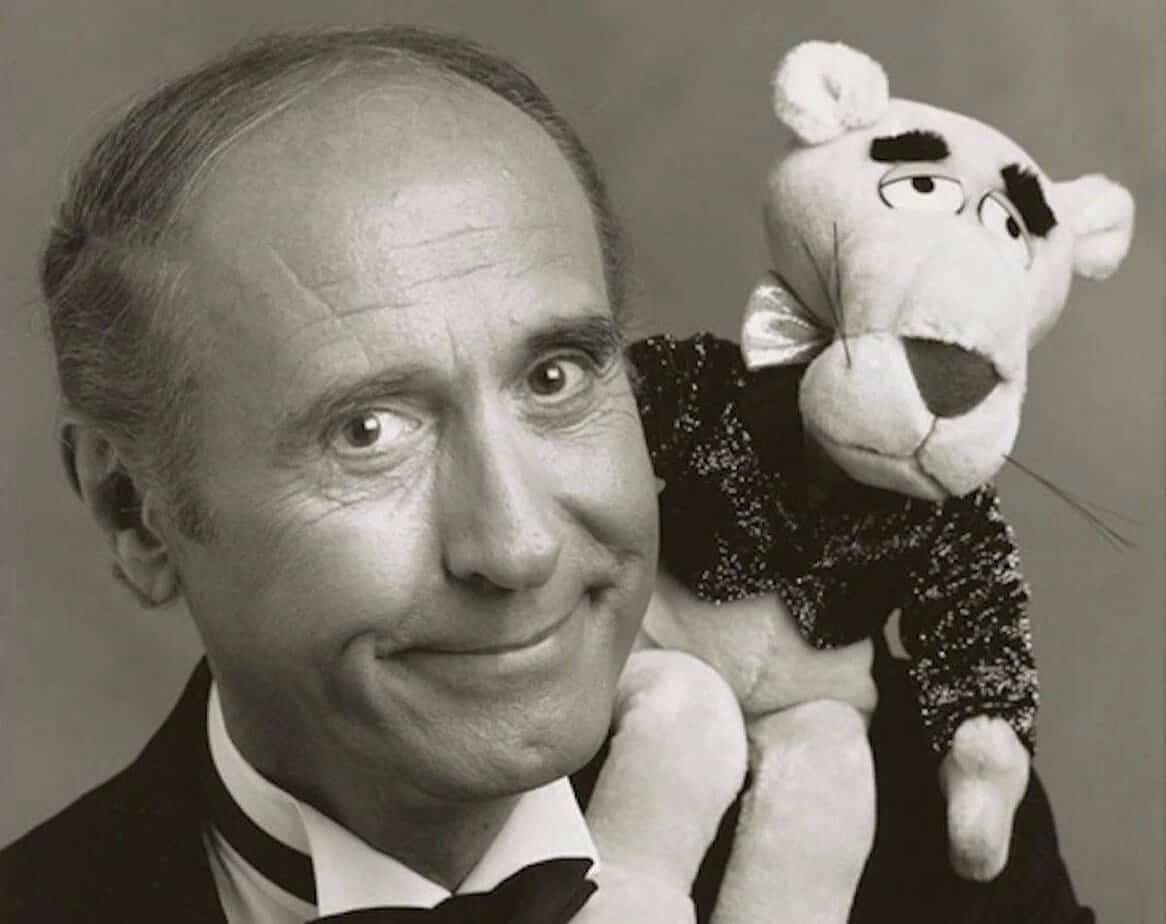

Henry Mancini with the Pink Panther

For a number of years, Mancini arranged music for dance bands and night-club acts, and also composed music for radio programs. Along the way he met the versatile and accomplished vocalist Virginia O’Connor, who suggested that they should settle near Los Angeles and that they should get married. Ginny was prominently connected in Los Angeles, counting Mel Torme, Mickey Rooney, Sammy Davis Jr., and Judy Garland among her acquaintances. She also was on friendly terms with the actor and writer Blake Edwards, who was on the verge of a meteoric rise as a movie director.

Mancini was quickly in demand, and he composed orchestral background scores for a dramatic radio series and also prepared music for club performances. He intuitively understood, however, that his success as a composer was dependent on some formal instructions in composition. As such, he took private lessons with three famous teachers. Alfred Sendry was a classmate of Bartók, “for whom the interval of the fourth was a favourite.” Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco had written concertos for Heifetz and Segovia, and Ernst Krenek was married to Gustav Mahler’s daughter and wrote twenty operas.

Henry Mancini: Darling Lili, “Whistling Away the Dark”

At Universal Studios

Henry Mancini in the studio

Joseph Gershenson, the music director of Universal Studios, hired Mancini for a period of two weeks to score a new slapstick comedy, “Lost in Alaska.” His music was deemed a success, and Mancini was hired as a Universal Studios staff composer. He worked alongside experienced men, such as Hans Salter, Frank Skinner, Herman Stein, and David Tamkin. Mancini arranged and composed, and he worked on a variety of films in different genres, including musicals, comedies, mysteries, B Westerns, and monster pictures.

Mancini was part of the so-called “Music Factory,” providing music for Universal Studios. His name was beginning to enjoy some recognition as an up-and-coming composer. However, Universal Studio was in trouble, and an uninvited takeover forced them to sack its entire music staff. A biographer writes, “The era of assembly-line films and patchwork scoring was over.” Universal Studios turned to the new medium of television, and Mancini was hired by Blake Edwards as the composer for the new television series, Peter Gunn. A recording of Mancini’s theme music for the show became a resounding hit.

Henry Mancini: Peter Gunn, “Theme Music”

Hollywood Fame

Between the early 1960s and the late 1980s, Mancini composed roughly three or four film scores per year, including more than two dozen that were written, produced, and/or directed by Edwards. His greatest influence as a Hollywood composer falls into the period from around 1958 to 1965, when he pioneered a new style of scoring. His success might well be gauged by his four Academy Awards, a Golden Globe, and twenty Grammy Awards. In 1995, Mancini was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Mancini detailed his method of scoring in an interview. “I have always been a creature of texture,” he explained. “The way instruments blend with each other, the voicing, the way the chords are voiced…Those little varying adjustments you make when you are looking at the drama of an arrangement or the balance of a piece. Knowing the orchestra is like a mechanic’s set of tools, and I think I know it pretty well.”

Henry Mancini: Charade (Henry Mancini Chorus; Mancini Pops Orchestra; Henry Mancini, cond.)

Legacy

Caricature of Henry Mancini

Henry Mancini had his finger squarely on the pulse of his time. He carefully studied all the trends and vogues in music, including ethnic tonalities of China, Russia, and traditional Inuit music. Thus prepared for any film score assignment, Mancini “kept seeking new layered harmonies, more complex melodic structures and a more dramatically developed architecture in his scores.” He even wrote a series of pop tunes clothed in a more serious orchestral language.

Mancini became a brand name in pop culture. He had invented a new language of film scoring that had a cosmopolitan feel and a lyrical sense of “cool.” Essentially, Mancini wrote a combination of timeless pop melodies with jazz inflections. While working on the Broadway stage version of Victor/Victoria, Mancini died of pancreatic cancer in Los Angeles on 14 June 1994. Shortly before his death, he created a scholarship at UCLA, and some of his library and scores are archived at UCLA and the Library of Congress.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter