Behind the Keyboard with Mandy Chan

Discover Hong Kong harpsichordist Mandy Chan’s insider view about historical technique, interpretation and the performer you should seek out.

©Musée de la musique/Jean-Marc Anglès

Friends often seek personal advice about how to build the perfect classical music playlist, particularly on the best classical piano music. In today’s digital age, accessing classical music has never been easier, just before exploring the world of classical composers and their piano masterpieces, it’s crucial to know more about the instrument itself and its ancestor, the harpsichord.

Left: Playing Harpsichord was a routine of elite women who curated their lives with elegance and sensibility.

(Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Portrait of a mother and father with their daughter at a harpsichord, 1780, Sotheby’s London.)

Right: Factory production of the piano achieved a high degree of perfection in the 19th century and introduced its magnificent sound and music to countless bourgeois women.

(Auguste

Renoir, Jeunes filles au piano,1892, Musée d’Orsay.)

The debate between the piano and the harpsichord seems to be ongoing, having played the piano for thirty-five years and the harpsichord for thirty years, which is superior? From my own experiences, I can reveal that the difference between them may not be as pronounced as we expect. Regarding the difficulty of playing, mastering the art of music is a demanding pursuit regardless of the instrument chosen, and harpsichord technique is not easier than piano. While the harpsichord of course might be criticised for its limited dynamic range and rigidity, the piano is not without its flaws, as it produces sound through hammers striking strings, resulting in a percussive-nature tone. When it comes to the expressive capabilities of music, both instruments offer unique advantages—if you wish to evoke the ancient timbre and polyphonic texture, the harpsichord is ideal; if your focus is on rich melodic contour with a contemporary touch, the piano is more suitable.

Harpsichordist Justin Taylor – Bach’s English Suite No.2 BWV 807: Prelude

The harpsichord naturally possesses an identifiable sound timbre across various registers, which brings polyphonic

writing and contrapuntal texture to our ears.

Pianist Beatrice Berrut – Bach’s Air on the G String

Largely due to its modern piano interpretation, this rare and beautiful baroque tune has become popular on the internet. Piano legato and nuances sound quality reminiscent of the baroque opera singer.

The above is a general guideline. The key lies in the art of performance, both instruments offer equally well expressive capabilities in the hands of proficient musicians. I find it difficult to assert that certain musical thoughts and emotions can be expressed solely through the piano or exclusively through the harpsichord. The golden rule of musical interpretation remains consistent: We delve into the deep meaning of the music and express that effectively. Musical ideas should be clear, emotionally resonating, thoughtful yet lively, and the tonal quality should captivate the audience without being overly sweet.

Harpsichordist Fernando Cordella – Bach’s Chaconne

Harpsichord might sound tougher than it appears. The majestic rhythm of this chaconne originated from baroque dance, to realize it on harpsichord demands precise control over both the duration of sounds and the silence in-between notes, which is known as articulation.

J. S. Bach once said, “Play the right note at the right time.” The piano requires a high degree of precision and control, while the harpsichord with its delicate touch demands equal mastery. Unlike the piano, the harpsichord’s expression does not rely on dynamics or volume; rather, it thrives on the art of articulation. Even without the piano’s sustain pedal, a successful harpsichordist plays well-articulating notes, sonorous yet delicate touch and at-ease speed while resonating audiences with musical visions.

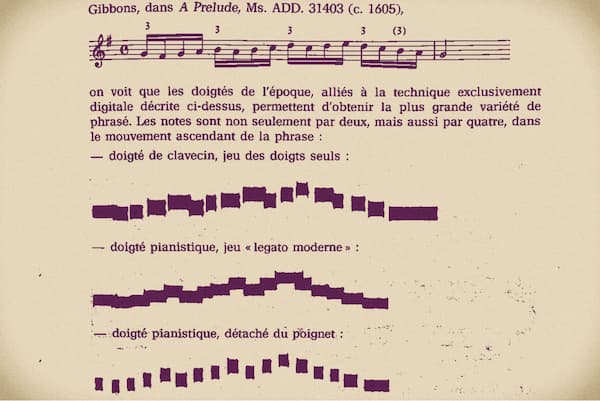

Three Sonagramme for articulation comparison of the same phrase from a prelude by Gibbons (c.1605):

-harpsichord early fingering

-modern piano fingering legato

-modern piano fingering staccato

Source: Dechaume, A.G. (1986). Le language du clavecin

Left: “Why do some harpsichords have two keyboards?” This design is to accommodate a range of strings hidden behind them. As harpsichordists, we select from these strings for a ideal sound quality that perfectly complements the music.

Right: Black colour of the keyboard traces a historical fascination with the exotic wood, ebony, dating back to the 16th century when both ivory & ebony were luxurious materials in Europe.

(Images: Le clavecin d’Antoine Vater, Paris, 1732, E.2008.2.1

© Musée de la musique/Jean-Marc Anglès)

Despite their differences in design and sound mechanisms, both instruments offer diverse interpretations of the same piece of music. But I cannot deny my inclination towards the harpsichord, behind its grandeur decoration lies the genuine essence of music — a musical rendering — which always involves a dialogue between the composer, the performer, and the audience! The composer should feel fulfilled, the audience should be delighted, and the performer must also feel satisfied in their judgment of expression. As a performer, the specific choice of instrument matters less, but for the sake of the composers from the 16th to 18th century, the harpsichord inclines more naturally with the spirit of their period compared to the modern piano.

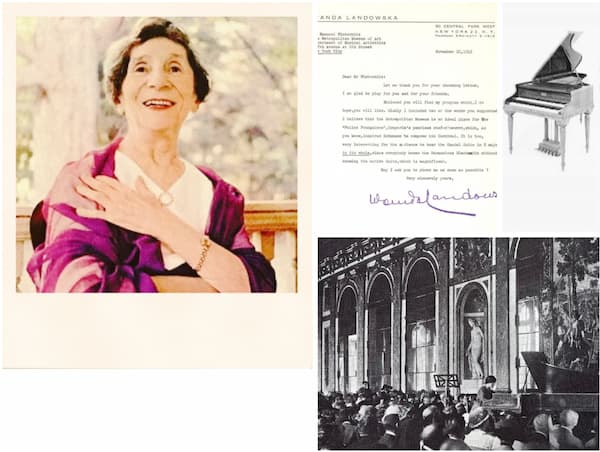

Left: Wanda Landowska, a celebrated harpsichordist, teacher, and musicologist who led the

groundbreaking harpsichord revival movement that persisted across two wartime periods. (©David Zingg)

Middle: Confirmation letter for a postwar concert in New York, 1945.

Upper Right: The 1928 Pleyel pedals harpsichord, which she loved and lived with throughout her life. (The MET Museum)

Bottom Right: Interior view of Landowska’s earlier performance in the Hall

of Mirrors at Versailles, 1921. (Plate 5, Secker & Warburg. (1965) Landowska on Music.)

Inside the expansive setting of today’s concert hall, the harpsichord appears to be far too courteous. I believe that contemporary harpsichord performance will benefit from lessons drawn from the tone palette of piano playing. In other words, it is unnecessary to build a rigid wall between the two instruments, as music has a historical continuity and

performers can transcend traditional boundaries and bridge the gap between tradition and modernity. Some historically informed performance advocates assert that baroque music should exclusively be performed on period instruments, this can mislead beginners into thinking that the use of harpsichord alone is sufficient to make authentic music. Those historical performance treatises, early fingering systems … etc. are easily neglected.

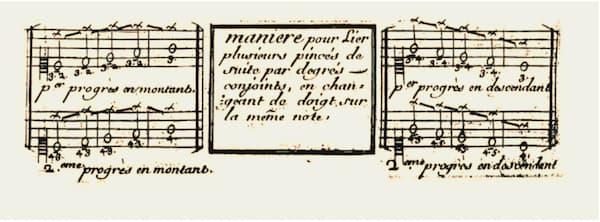

Examples of harpsichord fingering by baroque composer François Couperin’s book L’Art de toucher le clavecin (1716-17), he emphasised that: “The manner of fingering plays a significant role in playing harpsichord music…and substitute finger (3-2) on the same note is important for a legato quality.”

Left: Portrait of Farinelli, 1734, Royal College of Music London. This painting provides a glimpse of a splendid gilded-bronze legs side by side to Baroque’s iconic castrato.

Middle: French Harpsichord by Jean-Claude Goujon, 1749 & Jacques Joachim Swanen, 1784. E.233 Musée de la Musique Paris. Curvy cabriole legs gained popularity in the early eighteenth century, and serve as a rare example of rocaille design in three dimensions.

Right: The Limited production capacity of harpsichord makers is inadequate to satisfy the high demand, artisans are restoring and upgrading old harpsichords with enlarged keyboards plus new decoration.

The Chinoiserie theme of imitating black lacquer from China/Japan reflects contemporary cultural concerns and ornamental tastes in context

I enjoy playing harpsichord and always confident to draw inspiration from the piano’s rich tone palette, my childhood piano training has played an important part in my harpsichord progress and artistic integrity. However, I strive to avoid transplanting my piano skills directly to harpsichord playing, as they are two different musical languages. To conclude, balancing influences from both instruments without compromising their unique qualities is crucial for achieving a modern engaging performance.

Listen to the melodies I conjure on my harpsichord, as I unfold the enchanting sounds of French lute-style harpsichord music.

The bare surface of the left side of this museum harpsichord proved that it had been positioned against the wall inside the room during all performance occasions in the past.

(Image: Le clavecin Jean-Claude Goujon (1749) & Jacques Joachim Swanen (1784), E.233

© Musée de la musique/Jean-Marc Anglès)

Listening attentively to both the piano and the harpsichord, everyone will grow in maturity and develop a deeper appreciation for the intricate musical details. Classical music isn’t a one-hit wonder, instead, it’s like a fine wine gets better with each sip, inviting both audiences and musicians to enjoy more and more its beauty.

Mandy Chan has decades-long experience with the harpsichord, she is one of the rare Hong Kong harpsichordists who is willing and able to work with an unprejudiced mind on both a “kopie” type of instrument and on an instrument

Mandy Chan has decades-long experience with the harpsichord, she is one of the rare Hong Kong harpsichordists who is willing and able to work with an unprejudiced mind on both a “kopie” type of instrument and on an instrument

with pedals.

Mandy currently teaches at Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Research Centre for Gerontology and Family Studies) on classical music and arts appreciation courses, particularly aimed at older adults.

Mandy holds a BA from The University of Hong Kong (HKU) with a major in Music and studied Fine Arts, she acquired two LTCL Diplomas in both Harpsichord Performance and Piano Teaching. She completed her Decorative Arts Studies at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London.

Musician turned entrepreneur, Mandy is a former fashion buyer and also co-founder of a pre-owned luxury fashion company. Her experience in music and luxury retail led to her role as a music luncheon speaker at HKUAA, focusing on exposing classical music to wider audiences in Hong Kong.