Enrique Granados : Goyescas Book I

Francisco Tárrega : Capricho Arabe

Isaac Albéniz : Piano Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 78, “Concierto fantastico”

Spain, at the time of Goya’s birth in 1746, wrote one of his contemporaries, was “a body composed of many different parts, separated, and in opposition to one another, which oppress and despise each other and are in a continuous state of war”. Just 46 years before Goya’s birth, the last of the Spanish Habsburg monarchs, Charles II (“The Mad”), had finally died and with him any remaining fantasy of the “Golden Age”. A French Bourbon Prince, Philip, ultimately became his successor. “God be praised”, a Spaniard was heard to exclaim, “the Pyrenees have disappeared. Now we are all one!” But of course, this was not to be…. Spain again became a bloody battlefield for many more years.

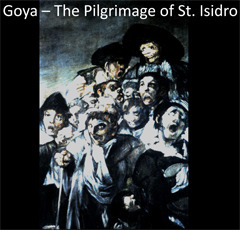

In Goya’s time, Spain’s society was stagnant and decadent. Fuentetodos, where Goya was born, was bleak and barren, as desolate as the inner lives of its inhabitants. Poverty and isolation drove Goya’s creative energy to search for a sense of humanity and passion, which found its expression in his art, on his canvasses. Goya’s body of work, and in particular his ‘black’ paintings (The Witches Sabbath, The Disasters of War, The Vision of the Pilgrims of St. Isidro, etc.) can be seen as such. In his painting, The Inquisition Trial, the accused wear penitents’ clothing and tall, cone-shaped hats – and show utter despair, their fate already sealed. The clerics sit back smugly to watch the ‘show’. Goya hated the Inquisition, which was still active during his time, and he conveys his emotion through the harsh reality of the scene.

Goya’s paintings find resonance in the music of Enrique Granados’ composition, Goyescas, and they also forecast the surrealist visions of Spanish and French artists, such as Dalí and Buñuel, Breton and Apollinaire.

In 1789, when Goya became court painter to the king, Charles IV, he produced the extraordinary portrait of The Royal Family. Their ‘costumes’ glitter with wealth and the ostentation of their rank, and yet the faces of the King and Queen show their shocking lack of character. Théophile Gautier observed that “they looked like the corner baker and his wife after they have won the lottery”. The queen in particular is shown in an unflattering fashion with a double chin, a thick neck and fat arms — her lover is included in the scene by Goya as an act of defiance of her husband, the King. Here, as in many of his portraits of Spanish aristocracy, intellectuals and friends, Goya bears witness of a new vision of humanity, centered more on individuality rather than on social status.

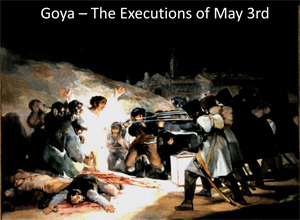

This new sense of reality is also found in Goya’s painting, The Execution of the Third of May, 1803, which shows French and Egyptian troops executing Spanish civilians who had opposed the French occupation. The immediacy of terror expressed in the painting resonated with painters of 19th century France, where civil war and especially the horror of the Commune de Paris (1870/71) found their expression in the art of the time, particularly in the paintings of Edouard Manet.

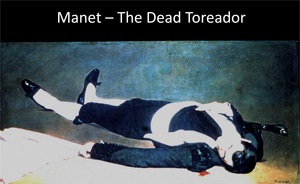

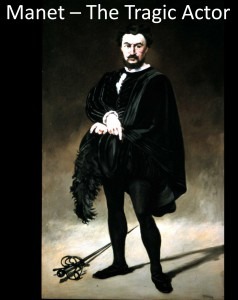

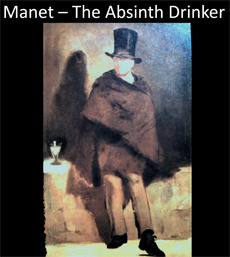

Manet’s The Dead Toreador and The Tragic Actor not only focus on Spanish themes, but the latter itself is a direct copy of Velázquez’ painting of an actor at the court of Philip IV. In The Old Musician, Manet places an old gypsy musician in the center of the painting next to the young girl and child, — again, a direct copy of a Velázquez; the two boys — a direct copy of a Watteau; the man with the tall hat – a copy of his own painting, The Absinth Drinker; and the ‘philosophe errant’ — a Jewish philosopher, cut off by the frame.

Although all of the protagonists are placed on the same level, the perspective changes between the different figures, some more clearly defined than others – questioning not only the very concept of ‘Renaissance’ perspective, but also the concept of ‘the original and its copy’ in art, which became a focus of artists in the 20th century.

Like Manet and other French painters of his time, many European artists, writers and musicians discovered Spain in the 19th century, and in turn, Spain itself contributed many world-famous artists. Cervantes’ Don Quixote was re-discovered as the first ‘modern’ novel. Spanish classical music, which had been in decline until the beginning of the 19th century, now saw a revival with the ‘zarzuela’ – a native form of opera interrupted by spoken dialogue. Spanish themes and settings became popular with opera composers and writers, as in ‘Carmen’ by Georges Bizet and ‘Hernani’ by Victor Hugo.

Fernando Sor, Miguel Llobet and Francisco Tárrega created many new and exciting compositions for the Spanish guitar, which found their way into the French musical repertoire, and the compositions of Felipe Pedrell, Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados and Manuel de Falla became inspirations for many artists, such as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel and Mikhail Glinka.

Please click here to read about the related in love article “To Russia with Love!”.