“Contesting the rubbish of effeminate song”

It might be difficult to believe, but at one time the art of counterpoint was considered “the child of ancient aberration.” Bach’s Art of Fugue was seen as hopelessly out of date, with the composer “playing to God and himself in an empty church.” The work needed a dedicated spokesperson, and counterpoint needed an advocate to save “music from the spreading rubbish of effeminate song.” And Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718-1795), a music critic, music theorist and composer known to enjoy a proper intellectual tussle in the public arena, took up the challenge. Apparently, Bach’s heirs approached the young theorist and promising writer on music to furnish an extensive preface for the second edition of the Art of Fugue. Marpurg carefully crafted an essentially modern music criticism that stressed, “while Bach’s music was profoundly intellectual and highly crafted, it also appealed to current aesthetic values; Bach kept to the golden mean, and demonstrated to anybody who would care to learn from him, how to combine an agreeable and flowing melody with the richest harmonies.”

It might be difficult to believe, but at one time the art of counterpoint was considered “the child of ancient aberration.” Bach’s Art of Fugue was seen as hopelessly out of date, with the composer “playing to God and himself in an empty church.” The work needed a dedicated spokesperson, and counterpoint needed an advocate to save “music from the spreading rubbish of effeminate song.” And Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718-1795), a music critic, music theorist and composer known to enjoy a proper intellectual tussle in the public arena, took up the challenge. Apparently, Bach’s heirs approached the young theorist and promising writer on music to furnish an extensive preface for the second edition of the Art of Fugue. Marpurg carefully crafted an essentially modern music criticism that stressed, “while Bach’s music was profoundly intellectual and highly crafted, it also appealed to current aesthetic values; Bach kept to the golden mean, and demonstrated to anybody who would care to learn from him, how to combine an agreeable and flowing melody with the richest harmonies.”

J. S. Bach: Art of Fugue, “Contrapuncti 1-4”

Surprisingly, we know very little of Marpurg’s early life. Born in the Margraviate of Brandenburg 300 years ago, he supposedly studied philosophy and music before becoming secretary to Count Friedrich Rudolf von Rothenburg, one of Frederick the Great’s closest advisers. Count Rothenburg was sent to Paris on secret treaty negotiations with Louis XV, and Marpurg went along. In fact, the theorist would spend much of the 1740’s in France. He became acquainted with some of the greatest minds of the Enlightenment, including the philosopher Voltaire, the mathematician d’Alembert and the composer Jean-Philippe Rameau. Upon his return to Berlin, Marpurg devoted himself almost exclusively to writing and editing books and periodicals about music. He eventually edited and essentially wrote most articles for his three music periodicals, authored thirteen books of a theoretical, practical, or historical nature and dutifully dabbled in composition.

Surprisingly, we know very little of Marpurg’s early life. Born in the Margraviate of Brandenburg 300 years ago, he supposedly studied philosophy and music before becoming secretary to Count Friedrich Rudolf von Rothenburg, one of Frederick the Great’s closest advisers. Count Rothenburg was sent to Paris on secret treaty negotiations with Louis XV, and Marpurg went along. In fact, the theorist would spend much of the 1740’s in France. He became acquainted with some of the greatest minds of the Enlightenment, including the philosopher Voltaire, the mathematician d’Alembert and the composer Jean-Philippe Rameau. Upon his return to Berlin, Marpurg devoted himself almost exclusively to writing and editing books and periodicals about music. He eventually edited and essentially wrote most articles for his three music periodicals, authored thirteen books of a theoretical, practical, or historical nature and dutifully dabbled in composition.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: Capriccio

Directed at the middle-class musical amateur, the Marpurg periodical Der critische Musicus an der Spree (Music Critic along the Spree River) ran for 2 years. It presented light-hearted discussions of musical topics of the day, and also included a course in elementary music theory. His Historisch-kritische Beyträge zur Aufnahme der Musik (Historical and critical reports on Music) was a professional journal that included book reviews, short biographies of important musicians, musical inventions and addressed a number of theoretical questions including tuning and temperament. Kritische Briefe über die Tonkunst (Critical Letters on Art Music) presents a collection of letters composed on behalf of an imaginary society. Addressed to various musicians, Marpurg engages in a highly volatile and personal spat with his theorist colleague Johann Philipp Kirnberger, publishes a lengthy series of articles about the composition of recitative, and prints 59 short musical compositions by contemporaries. Over time, Marpurg’s critical approach underwent a fundamental shift of emphasis. Rather than investigating the effect music had upon a given audience, he turned his analysis towards the musical composition itself and to the exploration of the composer’s relationship to the work.

Directed at the middle-class musical amateur, the Marpurg periodical Der critische Musicus an der Spree (Music Critic along the Spree River) ran for 2 years. It presented light-hearted discussions of musical topics of the day, and also included a course in elementary music theory. His Historisch-kritische Beyträge zur Aufnahme der Musik (Historical and critical reports on Music) was a professional journal that included book reviews, short biographies of important musicians, musical inventions and addressed a number of theoretical questions including tuning and temperament. Kritische Briefe über die Tonkunst (Critical Letters on Art Music) presents a collection of letters composed on behalf of an imaginary society. Addressed to various musicians, Marpurg engages in a highly volatile and personal spat with his theorist colleague Johann Philipp Kirnberger, publishes a lengthy series of articles about the composition of recitative, and prints 59 short musical compositions by contemporaries. Over time, Marpurg’s critical approach underwent a fundamental shift of emphasis. Rather than investigating the effect music had upon a given audience, he turned his analysis towards the musical composition itself and to the exploration of the composer’s relationship to the work.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: Cinquieme Suite

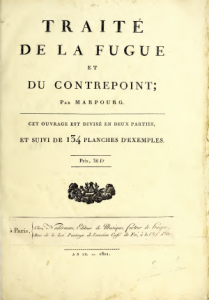

Marpurg wrote didactic works that covered keyboard performance, thoroughbass and compositions. However, he is probably best known for his theoretical treatise Abhandlung von der Fuge, published in 1753/54. Encyclopedically discussing the tonal counterpoint of J.S. Bach, Marpurg engaged in an authoritative discussion of fugal practice in late Baroque music. Considered old fashioned during its day, it was furiously reprinted during the first half of the 19th century, coinciding with the Bach revival instigated by Zelter and Mendelssohn. Marpurg spent the last thirty years of his life as a Prussian civil servant, and when Charles Burney met him in Berlin in 1772, he wrote, “I had the pleasure of being introduced to the M. Marpurg, a person who had so long labored in the same vineyard as myself…I found him to be a man of the world; polite, accessible, and communicative. His musical writings may justly be said to surpass, in number and utility, those of any one author who has treated the subject.” Marpurg’s compositions are an interesting but rather routine afterthought to his significant historical and theoretical contributions.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: “Jesu meine Freude”