When we imagine the stories from A Thousand and One Nights, we think of Aladdin, Ali Baba, and the 40 Thieves, which were added by the French translator Antoine Galland in the 18th century, or even Sheherazade herself, the story of the bride Scheherazade and her quest for life through storytelling has captured readers’ imaginations as much as it did her husband, Shahryar.

In its earliest versions, its tales came from India and Persia. Somewhere around the 8th century, these tales were translated into Arabic as The Thousand Nights, and from there, their international phenomenon began. Each new century added tales: Iraq’s tales were added in the 9th or 10th century, and Syria’s and Egypt’s tales came in the 13th century. To make the title true, eventually, enough tales were added to make 1,001.

These tales inspired artists, authors, rock bands, films, television series, and comic books. And, of course, composers. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov created his symphonic suite Sheherazade in 1888 and used less well-known stories for his source: Sindbad, The Kalendar Prince, The Prince and The Princess, and the Festival at Baghdad.

The tales of Sindbad the Sailor are familiar from popular culture, whereas the other three tales are less well-known. The Kalendars were wandering beggars, and in the 1001 Nights, there are stories of 3 Kalendar Princes, each of whom lost his exalted position and was cast down to beggary. The Prince and The Princess could be any love story and Rimsky-Korsakov waxes lyrical on their love. The final movement brings together elements of the earlier movements. The Festival is, essentially, a variation set on the theme from the Kalendar Prince movement. The Sea is the return of the Sindbad ideas, and the whole work ends happily, with Shahryar recognizing Scheherazade as his true companion.

In the first movement, we could read the two contrasting themes as Shahryar (Heavy brass) and Scheherazade (solo violin over brass). As befits any skilled storyteller, Scheherazade puts her listener (Sharhyar or you) in the centre of the action in the three climatic passages of the work. Rimsky-Korsakov’s skill in orchestration comes to the fore here – between the three episodes are two separating passages, which are otherwise identical except for the shifting of voices: the cello and the horn switch places, as do the clarinet and flute.

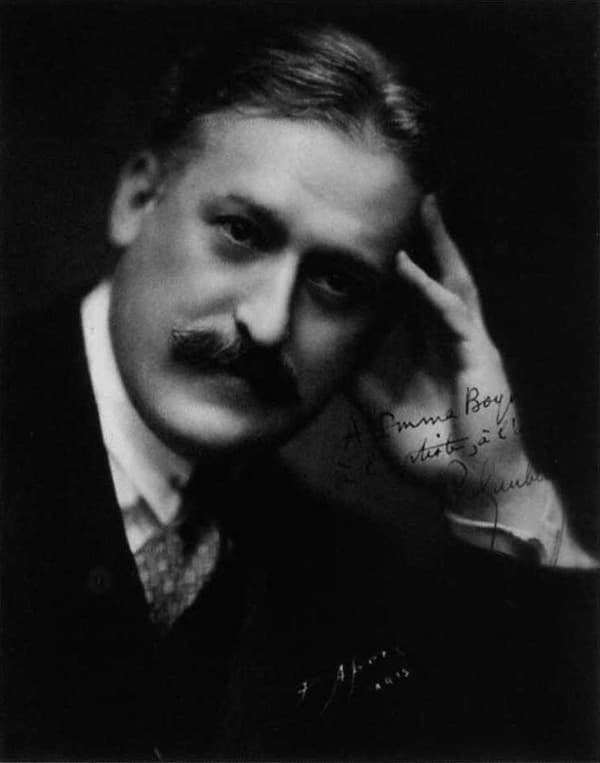

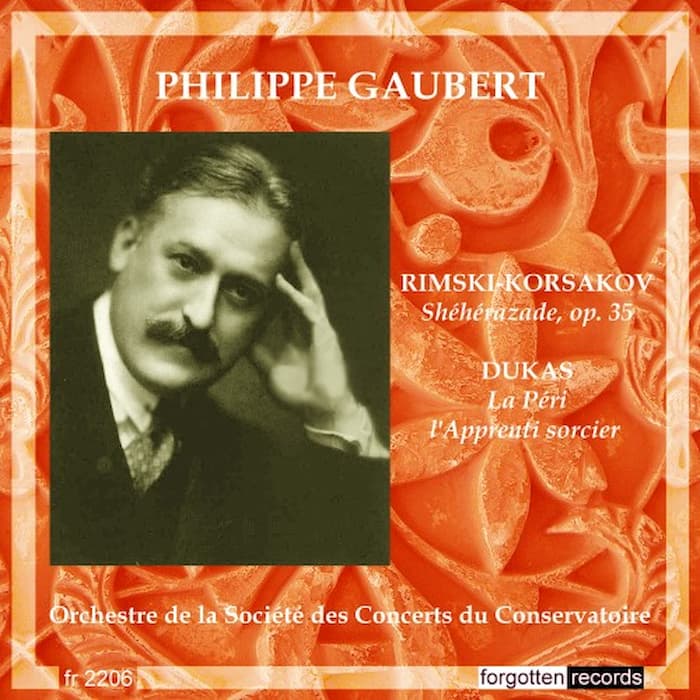

Philippe Gaubert, ca 1920

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Shéhérazade, op. 35 – I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship

This 1927 recording has Philippe Gaubert leading the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire. Philippe Gaubert (1879—1941) began studying flute at the Paris Conservatoire at age 13 and rose to be one of the most important French musicians in the inter-war years. He was not only a flute professor at the Conservatoire (Marcel Moyse was one of his students) but also the principal conductor of both the Paris Opera and the orchestra on this recording.

The Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire was founded in 1828 and was made up of the faculty and students at the Conservatoire. Gaubert was their chief conductor from 1919–1938, succeeded by Charles Munch. The orchestra folded in 1967, and a new orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, was formed, with Charles Munch returning as their music director for their first two years (1967–1968).

Performed by

Philippe Gaubert

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

Recorded in 1929

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter