The song Yankee Doodle started out as a way of making fun of one’s unsophisticated enemy. British military officers in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) had started to make fun of their colonial opponents as being ‘Yankee Doodle Dandies’, meaning someone who was trying to appear upper-class but getting all the signals wrong.

We can look at the modern version of the song and pick it apart

Yankee Doodle went to town

A-riding on a pony,

Stuck a feather in his cap

And called it macaroni.

[Chorus]

Yankee Doodle keep it up,

Yankee Doodle dandy,

Mind the music and the step,

And with the girls be handy.

Yankee, is, of course, someone from the US. The term probably comes from the Dutch name ‘Jan’ (pronounced ‘Yan’) and then made into a diminutive: Janneke = Yankee. English colonists used to call the Dutch colonists this name as an insult and then it was further applied by the British to the American colonists by the mid-18th century.

Doodle comes from another insult word: Dödel in Low German, meaning fool or idiot

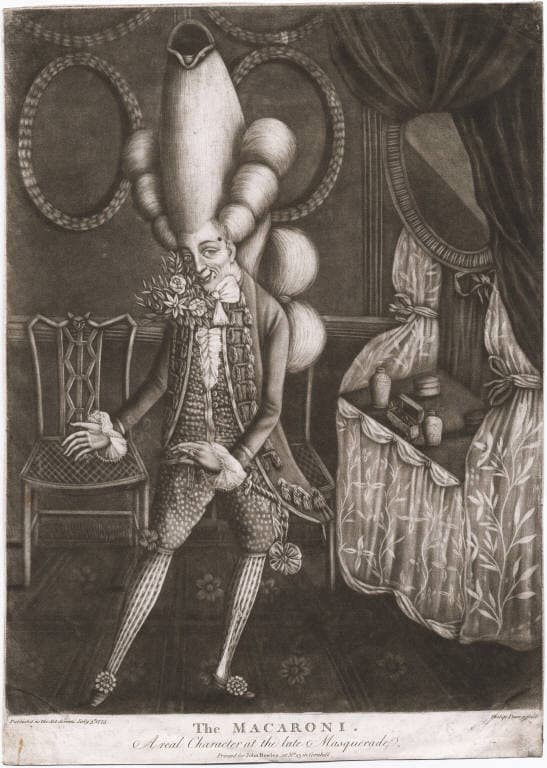

Macaroni was a kind of wig which then gave its name to a man of over-fastidious fashion in 18th century Britain. The pejorative term eventually was used to refer to someone who was considered a ‘fop’ and, in the song, our dandy thought that by merely sticking a feather in his cap, he would become a macaroni, whereas he was sadly mistaken.

Philip Daw: The Macaroni, 1773

A mocking song used first against the Dutch by the British, and then by the British against the colonists, the song, in the end, was taken by the new Americans as their own. Some of the original verses from 1775 refer to the cowardice of the American troops, how they would buy, rather than earn, their army ranks, and so on. One song sheet gave performance indications: ‘The Words to be Sung through the Nose, & in the West Country drawl & dialect’.

The first American verses for Yankee Doodle are credited to a British army surgeon, Dr Richard Schackburg, who wrote while he was attended to the wounded during the French and Indian War around Albany, NY, in 1755. Indeed, the British are said to have made fun of rag-tag American militiamen by playing the song as they headed toward the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775), which marked the first defeat of the British and the start of America’s move to independence.

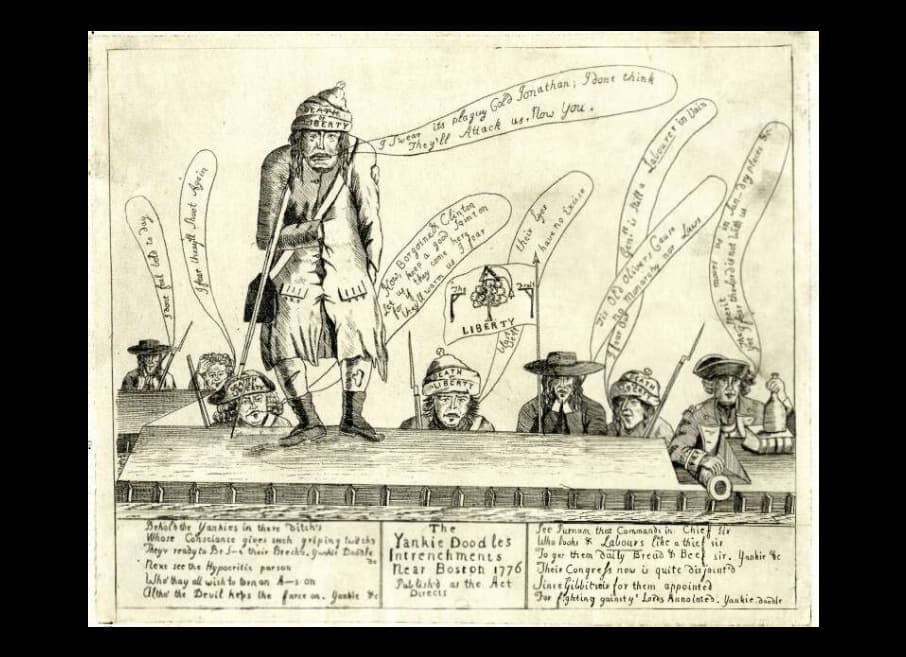

In a cartoon from a British loyalist newspaper in Boston, the rag-tag nature of the American army, with their hats saying ‘Death of Liberty’, with the man standing on the trench wondering if the cold will keep the British army away. A man dressed as a minister is saying, ‘I don’t feel bold today’. On the flag with the Liberty Tree, there are two gibbets, and the tree has a fool’s cap on its top. The local paper was very clear on their thoughts about this ridiculous uprising! Unfortunately, the verses below the image won’t fit the Yankee Doodle tune but were intended for another song, Doodle Doo.

British Loyalist newspaper cartoon: ‘The Yankie Doodles intrenchments near Boston’ ridicules the ‘Yankie Doodle’ militia, 1776

After those successful battles, the Americans turned the song to their own advantage. Following verses list the leaders of the American side, the growing size of the army, the quality of the armaments, the wealth of the provisions, etc.

Father and I went down to camp,

Along with Captain Gooding,

And there we saw the men and boys

As thick as hasty pudding.

[Chorus]

And there we saw a thousand men

As rich as Squire David,

And what they wasted every day,

I wish it could be savèd.

[Chorus]

The ‘lasses they eat every day,

Would keep a house a winter;

They have so much, that I’ll be bound,

They eat it when they’ve a mind to.

[Chorus]

And there I see a swamping gun

Large as a log of maple,

Upon a deuced little cart,

A load for father’s cattle.

[Chorus]

And every time they shoot it off,

It takes a horn of powder,

And makes a noise like father’s gun,

Only a nation louder.

And so on.

William Barnes Wollen: Battle of Lexington, 1910 (National Army Museum)

The song was always recognized as a parody and humorous, hence, even in the boasting version of the song, the singer decries the wastage of food, and later, the singer’s fear at seeing graves prepared for the coming dead causes him to run home to hide with mother.

Violin virtuoso and composer Henry Vieuxtemps (1820–1881) did three tours of America in 1843–4, 1857–8, and 1870–71. Upon his return from his first tour, he published a little work he had created for his local audience, his Souvenir d’Amérique’, a set of variations in the highest European style on their little funny song. The work is challenging and just as demanding as any other work for a violin soloist.

Henry Vieuxtemps: Souvenir d’Amerique, on Yankee Doodle, Op. 17 (Ruggiero Ricci, violin; Marco Vincenzi, piano)

That the song was first used against the Americans and then adopted by them as one of their national songs speaks more about the American humour than the British finger-pointing. Most Americans who sing the song now have to think that the ‘macaroni’ joke has to do with pasta and not fashion and that ‘sticking a feather in his cap’ was really a way of dressing up for town! You could also read it as indicative of success: We have a town! Our boy has a pony! He can dance to music! There are girls! The cynicism of the original British lyrics gets lost in a literal interpretation, which is another kind of humour and much more subtle.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter