Credit: http://www.ancestryimages.com/

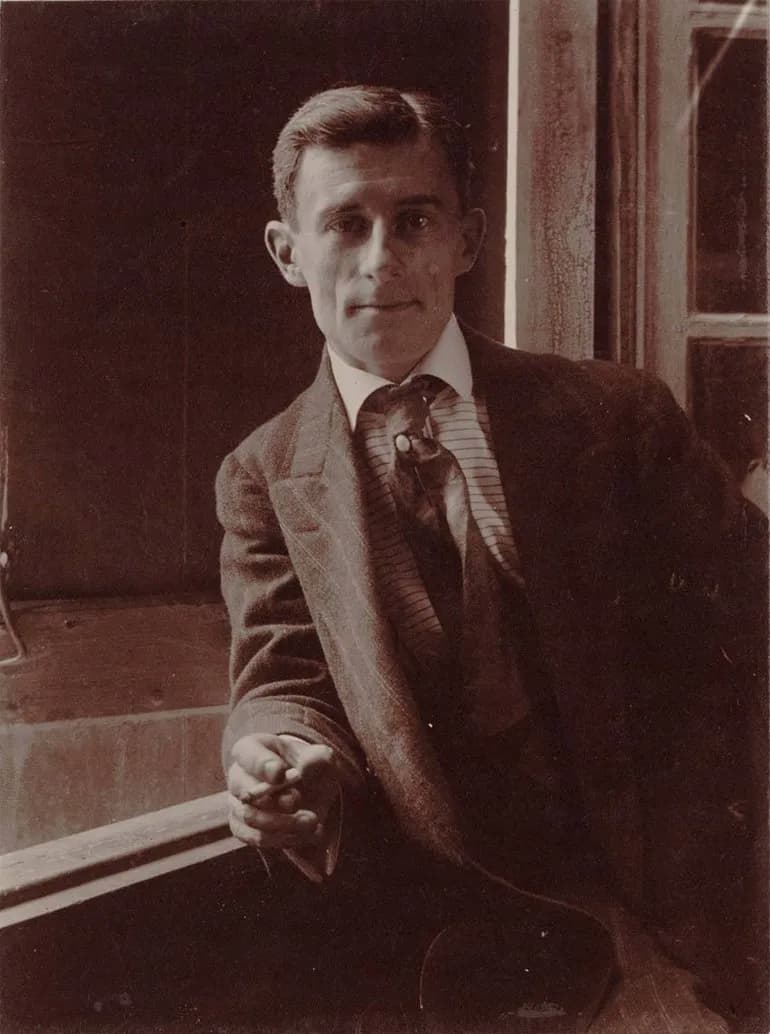

The Austrian composer and pianist Ernst Pauer (1826-1905) was a student of Mozart’s son, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart, before moving to London in 1851. He was one of the first piano professors at the Royal College of Music and also worked with the music faculty at the University of Cambridge.

One of his most interesting works is his book, The Elements of the Beautiful in Music, published in London in 1876. In the second chapter, he looks at the affective properties of keys, as did many other 19th century composers. But, unlike them, he actually listed works that he felt fulfilled his requirements.

Pauer saw the key of G minor as the key for the sentimental, but not the passionate. Its affect covers sadness, sometimes quiet and sedate joy, and a gentle grace with a slight touch of dreamy melancholy. Occasionally it rises to a romantic elevation – it can’t reach the passionate because of its innate sweetness. For his examples, he chooses works by Mozart, Mendelssohn, and Spohr.

Mozart’s Great G minor symphony (his only two symphonies in minor and both were in G minor), opens with an unforgettable theme that conveys that dreamy melancholy that Pauer described.

Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550: I. Molto Allegro (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra ; Roger Norrington, cond.)

In his Lieder ohne Worte, “Songs Without Words,” Mendelssohn created an entirely new genre of music, where the romantic song met the new pianism. These lyrical pieces took advantage of the popularity of the piano in middle-class drawing rooms around Europe. Mendelssohn wrote some 56 of these, some never published in his lifetime. The ‘Barcarole,” as Pauer has it, appears in the first collection of these piano pieces, and is called by Mendelssohn a “Venezianisches Gondellied” [Venetian Gondola Song].

Mendelssohn: Lied ohne Worte No. 6 in G Minor, Op. 19, No. 6, “Venezianisches Gondellied” (Venetian Gondola Song)(Peter Nagy, piano)

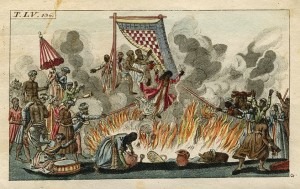

When Pauer selected an aria from Spohr’s opera Jessonda, of suttee and rescue, the opera was still in the common repertoire, but has now fallen away. The aria, which Pauer called in Italian “Onori military,” occurs at the beginning of Act II where Tristan discovers that Jessonda, who was destined to be burned in suttee on her husband’s funeral pyre, is his long-long love of his youth.

Spohr: Jessonda: Act II: Der Kriegslust ergeben (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Tristan; Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra;

Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

Although Pauer gave the affects for all of the other major and minor keys, he didn’t give us the musical references that he was thinking of. We’ll be posting his other key affects, so take a read and add your own suggestions. What’s your best all D minor (expresses a subdued feeling of melancholy, grief, anxiety, and solemnity) piece? Or perhaps you have a great idea for something in a pure E major (the brightest and most powerful key, expresses joy, magnificence, splendour and the highest brilliancy). Find your key and let us know!

Pauer’s definitions were definitely accurate in general, even past his time. A piece which has all the elements which Pauer definied for G minor was Tchaikovsky’s Arabian Dance (Coffee) from The Nutcracker. A gentle, nocturnal melancholy, flowing like a dark but calm sea