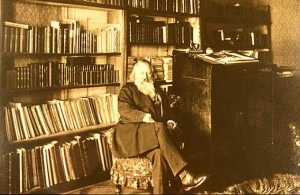

Producing a doctoral thesis in the humanities, especially when it involved archival research, used to be a lot of work. It frequently involved lengthy travel from library to library in order to research original materials related to the subject at hand. If your research subject turned out to be a famous composer, you could be assured that valuable letters, manuscripts and sketches had been scattered around the four corners of the globe. When I wrote my thesis on the compositional process of Johannes Brahms, I was supremely lucky that the “Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde” (Society of friends of music) in Vienna held all the composer’s personal books on music, music theory and a substantial number of his manuscript autographs. Actually, we are supremely fortunate that these treasures survived in the first place, as lawyers squabbled over the estate of Johannes Brahms for almost 18 years!

Producing a doctoral thesis in the humanities, especially when it involved archival research, used to be a lot of work. It frequently involved lengthy travel from library to library in order to research original materials related to the subject at hand. If your research subject turned out to be a famous composer, you could be assured that valuable letters, manuscripts and sketches had been scattered around the four corners of the globe. When I wrote my thesis on the compositional process of Johannes Brahms, I was supremely lucky that the “Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde” (Society of friends of music) in Vienna held all the composer’s personal books on music, music theory and a substantial number of his manuscript autographs. Actually, we are supremely fortunate that these treasures survived in the first place, as lawyers squabbled over the estate of Johannes Brahms for almost 18 years!

In May 1891, Brahms posted his last will in a letter to his publisher Fritz Simrock. This letter is known as the “Ischl Testament,” because Brahms sent it from his summer residence in the resort town of Bad Ischl. However, in April 1896 Brahms asked to have the letter back, and it was found in the middle drawer of his desk after his death. In the original, Brahms named two associations in Vienna and Hamburg, and bequeathed his books and musical effect to the Gesellschaft. Later he crossed out the two associations, and left everything to the Gesellschaft. During the final weeks of his life, Brahms approached Dr. Richard Fellinger to draft a testament, however, that document was never signed, and authorities had to go back to the amended letter of 1891.

In May 1891, Brahms posted his last will in a letter to his publisher Fritz Simrock. This letter is known as the “Ischl Testament,” because Brahms sent it from his summer residence in the resort town of Bad Ischl. However, in April 1896 Brahms asked to have the letter back, and it was found in the middle drawer of his desk after his death. In the original, Brahms named two associations in Vienna and Hamburg, and bequeathed his books and musical effect to the Gesellschaft. Later he crossed out the two associations, and left everything to the Gesellschaft. During the final weeks of his life, Brahms approached Dr. Richard Fellinger to draft a testament, however, that document was never signed, and authorities had to go back to the amended letter of 1891.

A couple of days after Brahms’s death, his estate was taken into the custody of the court. But there was an immediate problem as to which court should have jurisdiction. Since Brahms had never applied for Austrian citizenship, jurisdiction was still in Hamburg. To solve the problem, Hamburg gave up their claim, and Brahms was made an Austrian citizen posthumously. The Gesellschaft demanded to be considered the sole heir, while the Liszt Pension Fund in Hamburg and the Czerny Foundation in Vienna insisted that the original “Ischl Testament” should be honored. A Viennese lawyer, meanwhile, had gained power of attorney to act on behalf of 22 possible heirs. All manner of distant relations from Hamburg and as far away as Philadelphia, Chicago and Minnesota demanded a piece of Brahms’s considerable wealth. Before the courts made their decision, the Gesellschaft managed to conclude a special agreement on 23 June 1900, that “it would receive—immediately and irrevocably—Brahms’s books and musical effect, including his own and other musical autographs.”

On 5 March 1901, the Viennese courts ruled that the corrections made to the letter of 1891 were unclear and contradictory, and that the 22 people represented by the Viennese gold digger were recognized as legal heirs. In the unsigned testament drafted by Dr. Fellinger, Brahms had ordered all letters and correspondence to be destroyed. Since this testament was invalid, the letters became the official property of the 22 heirs. So Dr. Fellinger, who had been the trustee of the Brahms estate in 1897, asked for power of attorney to return the letters to their senders or to destroy them. The Viennese bloodhound objected, and the matter went in front of the courts. They decided that the heirs and the Gesellschaft should nominate a delegate to open the letters to Brahms, which had been put under seal by the court. That expert was the Viennese lawyer and music lover Dr. Erich von Hornbostel, who was also a pioneer in the study of non-European music. Since Hornbostel did not keep notes of his work on the letters, we have no idea which ones he destroyed, and which letters were handed back to sender.

On 5 March 1901, the Viennese courts ruled that the corrections made to the letter of 1891 were unclear and contradictory, and that the 22 people represented by the Viennese gold digger were recognized as legal heirs. In the unsigned testament drafted by Dr. Fellinger, Brahms had ordered all letters and correspondence to be destroyed. Since this testament was invalid, the letters became the official property of the 22 heirs. So Dr. Fellinger, who had been the trustee of the Brahms estate in 1897, asked for power of attorney to return the letters to their senders or to destroy them. The Viennese bloodhound objected, and the matter went in front of the courts. They decided that the heirs and the Gesellschaft should nominate a delegate to open the letters to Brahms, which had been put under seal by the court. That expert was the Viennese lawyer and music lover Dr. Erich von Hornbostel, who was also a pioneer in the study of non-European music. Since Hornbostel did not keep notes of his work on the letters, we have no idea which ones he destroyed, and which letters were handed back to sender.

Brahms’s fortune and personal possessions went to the 22 heirs and predictably, were never seen again. When Brahms’s old flat in the Karlsgasse was torn down in 1906, his furniture was stored for a couple of years. Some pieces were destroyed in WW2, while his piano chair, a rocking chair and a writing desk are currently housed in a room especially dedicated to Johannes Brahms in the Haydn House, part of the group of Viennese museums.

Johannes Brahms: Intermezzo Op. 118, No. 6

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life

Is it known, roughly, how much Brahms was worth when he died? I know he gave a lot of money away, but, presumably, he still was comfortably off.

Hi Dick. Apparently old Johannes did pretty well on the stockmarket as well as his compositions. He left 181,000 Gulden. For comparison he paid about 370 Gulden 2x a year to his landlady for a 3 room flat in Vienna during his last 10 years. His money was shared by 22 of the Brahms family from Hamburg to Pittsburg and Chicago after many years of legal wrangling