To attend a concert in mid November in Shanghai was like flying from Ben Gurion Airport. Tickets were required to be presented to enter the premises of the Shanghai Symphony Hall, which is unnecessary at normal times. Bags were requested to be checked in at the lobby instead of the cloakrooms downstairs, as one would expect at normal times. A photojournalist from Reuters, an agency that seems least interested in music but money, was interviewing members of the audience during the intermission. Something is going on here. Something is not right.

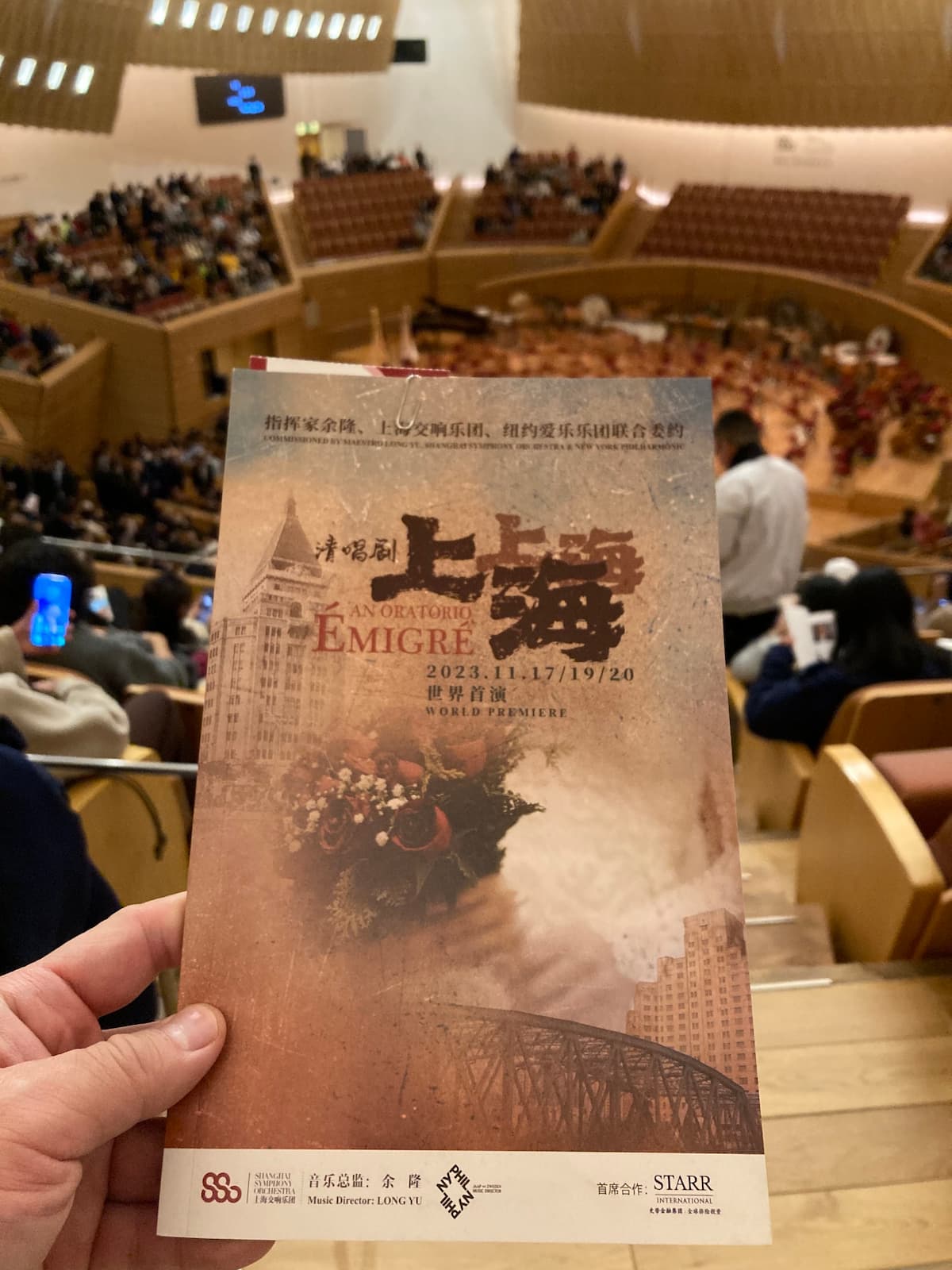

The premiere of Émigré at the Shanghai Symphony Hall

The world goes wrong in many ways. There are at least two distant battles fought at the frontiers to the west, one particularly connected to that night. On the bill was an oratorio about Jewish life in Shanghai. The seemingly dominance of the Jewish audience probably justified the presence of heightened security.

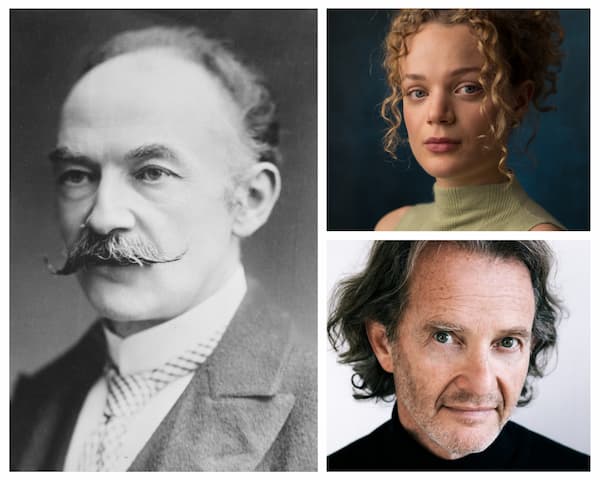

Embracing sensitive timing and navigating through tricky cultural crosswinds, Émigré, a joint commission by Maestro Long Yu, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, and New York Philharmonic, received its premiere on November 17th, with Long, who takes a personal interest by being a benefactor, conducting Shanghai Symphony, two mixed choruses and a strong cast of seven singers including household names bass-baritone Shen Yang and mezzo-soprano Zhu Huiling.

It loosely follows a storyline about the life of Jews taking refuge in Shanghai during the late 1930s fleeing Nazi Germany. The work remembers how the homeless Jewish people had to fight for survival at the dawn of WWII. The premiere came about a time when the Jewish people are again fighting for survival in an ongoing war at their ancient home now called Israel.

Dubbed an oratorio, Aaron Zigman’s lavish output sits comfortably on the fence, blurring the man-made boundaries between genres of staged music works. For me, it’s at some point too sensual to be recognized as an oratorio, and at others too trivial to be seen as an opera. It makes a fitting musical, though, with prayers sung in Hebrew (and Yiddish probably) deeply touching, and the tragic love story between two families mistrustful of each other at the beginning, one Jewish and one Shanghainese, salutes Shakespearean timelessness: Only through death come love and reconciliation.

There are lighthearted moments from the Mambo-Cabaret inspired final episodes at the end of the first act. The majority are set in a somber tone. The influence of klezmer is ubiquitous. But as a Shanghai indigenous, I could hardly see how the work is relevant in musical styles to the city that harbored some 20,000 Jews hiding from the Holocaust.

Or this is never the concern.

In any case, Émigré, a full-length music theatre in two acts divided by eight scenes and a prologue aiming for an international audience, must be the most ambitious undertaking to address the Hebraic legacy left by Shanghai following a string of musicals, operas, and theatres staged in China. And I couldn’t see why it’s not going to be the most popular one, given its forthcoming world tours to be performed by a fleet of high-profile orchestras across three continents in Hong Kong, New York, and Berlin under the baton of Long Yu, arguably the biggest single beneficiary out of this global effort.

Now we have a clear winner!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter