Nations frequently define themselves on the basis of shared ethnicity. This includes ideas of a culture shared between members of the group—derived from previous generations—and usually a common language. Membership in the nation is hereditary, with the state deriving political legitimacy from its status as the homeland of an ethnic group. To reinforce the status of a nation, it generally recognizes a number of special days throughout the year. China, for example, celebrates Women’s Day on 8 March, and honors its workers on 1 May. However, most significantly, the Chinese Nation celebrates the anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1. This yearly remembrance of the 1 October 1949 ceremony at Tiananmen Square is celebrated throughout Mainland China, Hong Kong and Macao with a variety of government-organized festivities. Military parades, flag-raising ceremonies, dance shows and extravagant fireworks displays come together in an elaborate display of power and ideology to provide emotional cohesion to the members of Chinese ethnicity. It is hardly surprising that music—above and beyond the National anthem—plays a significant role in such overt displays of national pride.

Nations frequently define themselves on the basis of shared ethnicity. This includes ideas of a culture shared between members of the group—derived from previous generations—and usually a common language. Membership in the nation is hereditary, with the state deriving political legitimacy from its status as the homeland of an ethnic group. To reinforce the status of a nation, it generally recognizes a number of special days throughout the year. China, for example, celebrates Women’s Day on 8 March, and honors its workers on 1 May. However, most significantly, the Chinese Nation celebrates the anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1. This yearly remembrance of the 1 October 1949 ceremony at Tiananmen Square is celebrated throughout Mainland China, Hong Kong and Macao with a variety of government-organized festivities. Military parades, flag-raising ceremonies, dance shows and extravagant fireworks displays come together in an elaborate display of power and ideology to provide emotional cohesion to the members of Chinese ethnicity. It is hardly surprising that music—above and beyond the National anthem—plays a significant role in such overt displays of national pride.

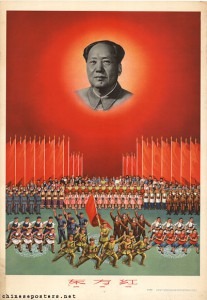

Li, Huan Zhi: The East is Red

One of the most popular songs heard on 1 October is the personal political anthem of Chairman Mao Zedong, “The East is Red.” Originally, this song was a romantic ballad originating in North Shaanxi Province under the title “Riding White Horses.” This love song became highly popular during the Second Sino-Japanese war, with patriotic words rousing the troops:

Riding white horses, armed with Western guns,

Three brothers with the Eighth Route Army. Living on its grain.

They’re thinking of girls back home again. But fight on against Japan.

In 1944, the Shaanxi farmer Li Youyuan and a rural schoolteacher wrote several new verses to the tune of the original song, praising life of the North Shaanxi Revolutionary District, the Communist Party and the leader Mao Zedong. This new version called “Migration Song” rapidly grew in popularity and contained the following verse:

The East is red, The sun, it rises. And in China, a Mao Zedong is born.

Further alterations by Communist Party lyricists produced three new stanzas, and the song was published under the title “The East is Red” in the Liberation Daily in Yanan. By 1949, the song was indispensably associated with the personality cult surrounding Mao Zedong, with “The East is Red” replacing the China national anthem. Furthermore, a highly popular 1964 play—suggesting that Mao was the only person capable of leading the Chinese Communist Party to victory—featured a central chorus performed by 2000 artists and a 1000 people chorus. During the Cultural Revolution, the song was played through PA systems in towns and villages across China at dawn and at dusk, and the Central People’s Broadcasting station opened its morning programming with the song played on a set of 2000 year-old bronze bells. Although the “March of the Volunteers” has since been adopted as the National Anthem, “The East is Red” remains highly popular. China’s first satellite launched in the 1970 happily beamed “The East is Red” back to Earth, and in 2009 it was voted the most popular patriotic song in China. And once again, on 1 October 2015, the old patriotic standby will sound far and wide. For some very old and tired people in the National People’s Congress in Beijing and the Executive Council of Hong Kong, this song remains relevant even as a modern China is rapidly emerging into the 21st century. Such is the power of ethnic nationalism!