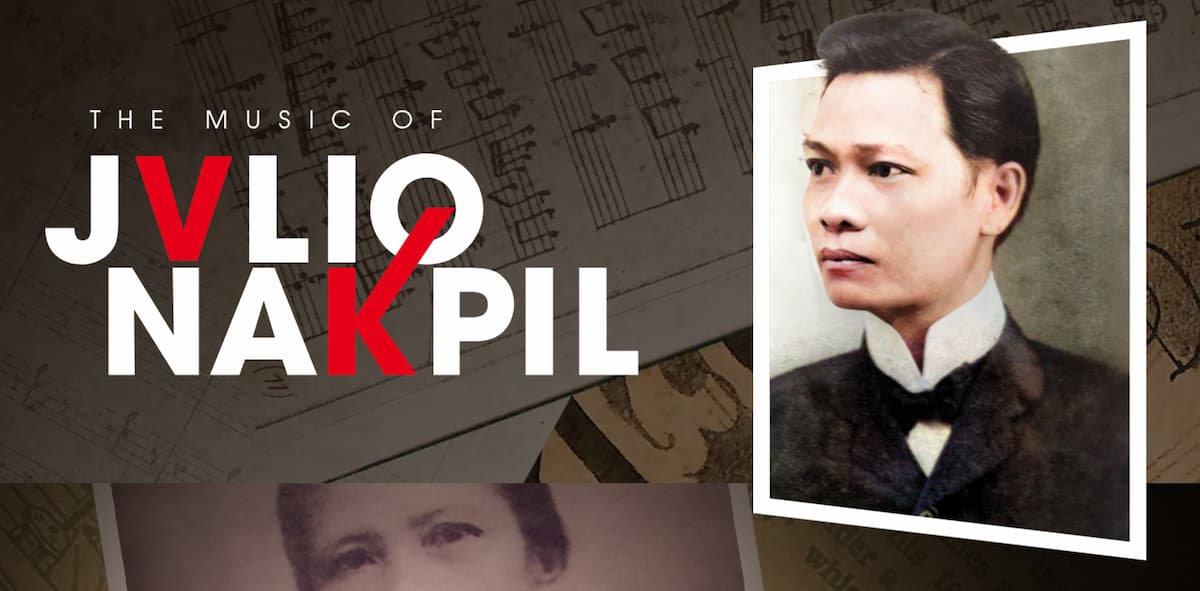

Meet Dr. Maria Alexandra Iñigo Chua, a musicologist and Professor at the University of Santo Thomas. She founded the Julio Nakpil Project, cataloging the vast manuscript of works written by pioneering 19th century Filipino composer Julio Nakpil (1867-1960). The two critical editions produced in this project are the first critical publications published in the Philippines. In this interview, Dr. Chua shares many exciting findings about Julio Nakpil.

The Making of Julio Nakpil Music Project

How did this project begin?

Dr. Maria Alexandra Iñigo Chua

I think it was around 2016 when a good friend of mine was curating a house in the center of Manila in Quiapo. He asked me to look for information about the musician who used to live in that house. I was studying at the University of the Philippines for my PhD and had access to the library. When I looked into it, I was astonished to find that many of his compositions were piano music. This was particularly striking to me as a pianist myself, as I had previously been unaware of his musical repertoire. Then, I got interested and undertook the task of cataloging his music. Toward the end of 2018, I submitted a proposal for the Julio Nakpil Project, which later received funding from the government. The project involved a number of musicologists, musicians and other scholars, and we conducted a study of his life and music. We embarked on endeavors to digitize and record his compositions. By 2022, we successfully compiled his works into two critical editions accompanied by four volumes of recordings.

Can you tell us a little bit about Julio Nakpil?

© Julio Nakpil

Julio Nakpil was a composer and revolutionary soldier and part of the Katipunan, a secret government trying to fight against Spain. Nakpil was ordered to write a national anthem, and he did. Unfortunately, Nakpil was not on the same Katipunan team as Emilio Aguinaldo. When Aguinaldo won the Revolution, he chose to have another anthem, but actually, it was Napkil who wrote the first conceived national anthem of the Philippines.

Even though Nakpil had written many musical works, he had never received any formal musical training; he took piano lessons for three months with his cousin, Manuel Mata, and then learned on his own. He also studied with his friend, Ramon Valdez, who was a violinist. Napkil might also have learned to read music from his father, who was a flutist and a jeweler. So technically, he was self-taught even though he would have some short lessons here and there. He did not perform much, but he had performed at Malacañang Palace (the current official residence and principal workplace of the President of the Republic of the Philippines; formerly was the residence of the Governor General of Spain in the Philippines). Another interesting thing about him was that he only had two years of formal education because the strict training of colonial schooling did not fit him; he would run around all the time, and his parents had no choice but to pull him out of school. But again, he was an autodidact and read a lot of books.

(performed by Christian Tan, Jr., Reynato Resurreccion)

So, when you look at his manuscript, did they make sense?

Yes, most of them followed Western structures, especially the ABA form. However, there are some unconventional harmonic progressions. For example, in his first composition, “Céfiro” (Zephyr), he employed a diminished 7th chord of the supertonic (ii) at the beginning of the piece. Additionally, in instances such as “Amor Patrio,” he utilized a diminished 7th chord without resolving it.

(performed by Heliodoro Fiel; Raul Sunico)

Did he compose differently before and after the Revolution?

His music before the revolution included bravura in the Chopinesque style, with all these arpeggios and running passages. During the revolution, he moved away from this performing style and wrote brief short pieces with Filipino titles, like the Pahimakas (Last farewell), Balintawak, and Pamitinan. Most of them are only two pages long.

(performed by Raul Sunico)

Were there any music societies in the Philippines that he was involved in during his lifetime?

He was a member of one society, but there were no findings that he had collaborated with other musicians. He never had any formal music training, so his music was rarely heard between the 1920s and 1940s. There is only one piano piece that became popular, the Recuerdos de Capiz.

Julio Nakpil lived during the Philippine Revolution, and his musical outputs displayed the transculturation of coloniality in a way. When I asked Dr. Chua if Spanish culture was a significant influence on his music, Dr. Chua responded:

(performed by Raul Sunico)

Yes, definitely. But not only Spanish, in a way, because he composed during the modern period of globalization, so there were influences of European and Latin American music and cultures. Much of his music was danza habanera, which actually originated from Latin America. After the revolution, his music became more nationalistic, utilizing Philippine musical forms in his works.

What is the next step of this project?

© themusicofjulionakpil.com/

There has been interest in performing his work, and hopefully, we can also include it in the music education curriculum here. We have also curated and organized concerts about his music. We would want a musical about his life using his music.

In addition to this project, Dr. Chua is a project leader of MusikaPilipinas, which aims to make lesser-known compositions by Filipino composers available. She is also a member of the study group in global history music of the International Musicological Society, and she will introduce Julio Nakpil and present some of his works in Mexico this August.

Learn about the Julio Nakpil Project

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter