“The Musical Quack”

Johann Kuhnau

300 years ago, on 5 June 1722, Johann Kuhnau (1660-1722) the immediate predecessor of Johann Sebastian Bach as Kantor at the Thomasschule in Leipzig, passed away after suffering from extended periods of illness. Kuhnau was not only a major figure in German music of the late Baroque, but he was also a polymath genius active as a novelist, translator, lawyer, and music theorist. His family originated from Bohemia, but they fled to Saxony during the Counter-Reformation because of their Protestant faith. Both his brothers were musicians, and Johann showed early evidence of his scholarly and musical potential. As such, he was sent to Dresden to study composition with a number of court musicians, and also took French and Latin lessons. He was musically active at the Kreuzkirche, and quickly noticed by the court Kapellmeister Vincenzo Albrici. A plague epidemic forced him to return home, but he swiftly left for the city of Zittau to further his education. Upon graduation, Kuhnau became a law student at the University of Leipzig and at the same time applied for the post of organist at the Thomaskirche.

Johann Kuhnau: Frische Clavier Früchte – “Sonata No. 2 in D Major” (Jan Katzschke, harpsichord)

Kuhnau: The Musical Quack title page

Kuhnau’s application was unsuccessful, “but he became increasingly active as a composer and performer in Leipzig, and when the post of organist at the Thomaskirche again became vacant in 1684 he was appointed to it.” While carrying out his duties as organist he completed and published his dissertation, began to practice law and got married. His fame as an organist grew and Kuhnau published all his keyboard collections, while simultaneously running a highly successful law practice. He continued his education by studying mathematics, Hebrew and Greek, and translated into German a number of French and Italian books. He also published a highly amusing satirical novel in 1700. “The Musical Quack” tells about the fictional exploits of Caraffa, a German charlatan who strives to make a name for himself as a musician by posing as an Italian virtuoso. Kuhnau offers fascinating observations about the social status of musicians, and criticizes “various musical practices including faulty text underlay, overelaborate thoroughbass realizations, the questionable art of the castrato, and the general ignorance of singers and musical institutions.”

Johann Kuhnau: Neue Clavier-Übung, Vol. 1, “Partita No. 5 in G Major” (Aniko Horvath, harpsichord)

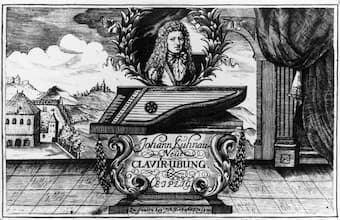

Engraving of Frontispiece for Kuhnau’s Six Biblical Sonatas

During this highly productive period Kuhnau also wrote sacred vocal music for performance in the several churches of Leipzig, including the Thomaskirche. When the Thomaskantor Johann Schelle died in March 1701, Kuhnau was almost immediately elected his successor. “As Thomaskantor Kuhnau reached the pinnacle of his career. He was exceptionally well qualified for the post, not only as a musician and composer but also as scholar, linguist and philosopher, and he carried out its heavy musical and teaching demands with distinction.” However, as a scholar explained, “the job was vexatious and difficult for him as for his successor J. S. Bach. During the final years of his life Kuhnau suffered from constant ill health, and he “grew deeply dissatisfied with the deteriorating conditions at the Thomasschule.” The young Telemann, who arrived as a law student in 1701 and immediately established a rival musical organization in the form of a collegium musicum, also undermined Kuhnau’s activities as a Kantor. Adding insult to injury, after Kuhnau had gone through several periods of illness, the town council officially asked Telemann to succeed him should he die.

Johann Kuhnau: Lobet, ihr Himmel, den Herrn (Opella Musica; Camerata Lipsiensis; Gregor Meyer, cond.)

Johann Kuhnau: New Piano Practise, 1689

Kuhnau was greatly esteemed, “displaying an element of medieval universality and mastered music, law, theology, rhetoric, poetry, mathematics and foreign languages.” His surviving music falls into two categories, as we find keyboard music primarily published before 1700, and sacred music that has essentially remained unpublished. Sadly, his entire oeuvre of secular vocal music, numbering close to 50 compositions, has been lost. Much of his reputation is based on four printed sets of keyboard pieces, including the “Biblical Histories.” These six multi-movement sonatas are prefaced by a prose description of a particular incident from the Old Testament illustrated in the music: The Fight between David and Goliath; Saul cured by David through Music; Jacob’s Wedding; Hezekiah, Sick unto Death and Restored to Health; Gideon, Saviour of Israel, and Jacob’s Death and Burial. A scholar writes, “Kuhnau’s purpose was to demonstrate, among other things, how keyboard music, without the benefit of a poetic text, could capture the emotional states emanating from an action or the description of a character. The various sections of each sonata bear Italian subtitles as clues to the particular emotional state or action being described by the music.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johann Kuhnau: Biblical Sonata No. 1, “Fight between David and Goliath” (Johannes Geffert, organ)