How does it feel to play that passage of Liszt or that section of Schubert beautifully? Or the grandest measures of Bach? The tenderest Chopin? The most sensitive, haunting Debussy? To plumb the profoundest, most spiritual depths of Messiaen?

How does it feel to play that passage of Liszt or that section of Schubert beautifully? Or the grandest measures of Bach? The tenderest Chopin? The most sensitive, haunting Debussy? To plumb the profoundest, most spiritual depths of Messiaen?

Fantasie in F minor, Op 49

Talking with my piano tuner recently, before he set to work voicing and regulating my piano, we discussed the philosophy of playing, a conversation which began with a reference to the Chinese Tao (or Dao), and the premise that “the right way is not always the right way“, a tenet which, as he pointed out to me, I should know all about, as both a teacher and a practitioner.

Those occasions when you’re playing and you feel yourself standing back from the music, allowing it to speak for itself, as if you are playing remotely, or floating above the piano, watching yourself play, are the most precious, and often signal the moment when a complete synergy of mind and body has taken place. Sportspeople often call it being “in the zone”, and musicians feel it too – a concept named “flow state” by the Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi to describe a mental state during which one experiences an energised focus, full involvement and enjoyment in the process of the activity, and a complete absorption so that one loses a sense of time and place.

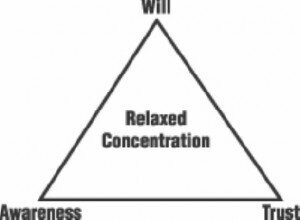

It is at times like this when the most profound insights about the music might be revealed, or when we feel truly in touch with the composer’s intentions and are truly able to communicate these to the audience. When you feel like that, your concentration levels are at their most intense, you are “in the zone”. And yet, you feel detached, floating, at one remove….. In his excellent book, The Inner Game of Music, author Barry Green describes this as a state of “relaxed concentration”, a state achieved through “trust, will and awareness”. In a study, it was found that classical pianists who entered a flow state experienced reduced heart rate and blood pressure, and noticeable relaxation in the major muscles of the face, particularly those used to produce a smile. In this state of “relaxed concentration” or what Csíkszentmihályi calls “effortless attention”, the pianists actually demonstrated improved performance as they played.

Try to recall what it felt like at that moment. How did your body feel? Your hands? The notes under your fingers? Try to store that feeling away for next time. Put it in your memory box and bring it out the next time you practice that piece. Gradually, the more times you repeat this exercise, the whole piece will evolve into something new, better, finer, and you reach a depth of understanding hitherto not experienced.

Try it.

Note:

1. de Manzano, Ö., Theorell, T., Harmat, L., & Ullén, F. (2010). The psychophysiology of flow during piano playing

Further reading

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row

More Opinion

-

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear' - The 12th Hamamatsu International Piano Competition

Judgement Explore how they're setting new standards in competition judging -

Has The Leeds Piano Competition Gone Woke? The Leeds Piano Competition's new guidelines spark debate. Share your thoughts!

Has The Leeds Piano Competition Gone Woke? The Leeds Piano Competition's new guidelines spark debate. Share your thoughts! -

Nurturing the Musical Brain It is essential to make music part of someone’s development as early as possible

Nurturing the Musical Brain It is essential to make music part of someone’s development as early as possible