© The Vital Gaitway, Center for Body Education

Musicians contribute so much to the personal and cultural well-being of the community and play music because they love it. Given that, it is a shame that for some, a career and/or long-term love of playing is associated with levels of stress and discomfort – sometimes a great deal of stress and discomfort. There are musicians who have become so injured as a consequence of their playing that they have been unable to continue with their beloved music making. Thankfully that is not everyone, but in the ranks of committed musicians, struggling with well-being while performing at their best is more common than you might realise.

That statement is supported by research into musicians’ wellbeing that is growing year by year1. As a result, physical and psychological struggles with playing, particularly high intensity playing, is being increasingly recognised as a professional problem that needs to be addressed.

This series of articles from BodyMinded in Australia aims to provide a practical guide to preventing and addressing playing related injury and stress, and in the process support development of musical potential at all levels of achievement.

If your focus is on performance, rather than dealing with injury, these articles will also provide support. Musicians move in order to make music, and as an embodied sense of how to cooperate with your own structure and your instrument takes hold, you will find your instrument becoming an integrated extension of the sense of yourself and the music will flow increasingly with ease, power and facility2.

And finally, after years of providing professional development training for music teachers, I’m aware of how deeply teachers take their responsibility for the well-being of their students. Creatively teaching safe body-use as a part of music lessons will help to prevent the kinds of difficulties that often arise when a musician becomes more serious and begins spending many more hours playing.

Treating the instrument as an extension of the self is common amongst long-term instrumentalists. I had a student in a workshop one day who, when I said “hello”, leant sideways to reply to me. Curious about that, I moved to the other side of the person and asked another question. Sure enough, he leant to the other side in order to answer! The next day he came to a musician’s class, with his instrument. A large tuba, which he sat with on his lap…

© K.C. Strings Violin Shop

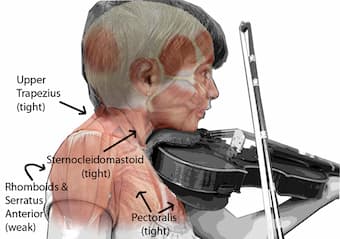

Let’s get started with a practical illustration. Many instrumentalists experience shoulder and neck stiffness or discomfort, or experience heaviness in the arms after playing for a while. Here is a simple question: where do your arms attach to your body? Take a moment to point or touch that part of your body. Did you point to the outside of your shoulders? This is most usual representation.

Now feel your collarbones, at the top front of your chest. Feel along towards the centre until you find the bump where the collarbone attaches to the breastbone. This is the only bony joint where the arm bones attach to the rest of the skeleton. You can feel this by using one hand to feel how your collarbone moves as you lift the other arm. Can you feel it? When your arm moves the whole shoulder girdle (collarbone and shoulder blade) are involved. The arms are suspended from the spine, via those shoulder and neck muscles that are sometimes so uncomfortable. The shoulder blades are embedded in muscles that mean they can move a whole lot; up, down, forward, back, always in support of and following the movements of the arm.

This means that when you raise or use your arms for any purpose, your shoulder girdle is involved. The collarbones and shoulder blades are arm bones! See what happens if you try to keep your shoulder girdle held still or back while moving your arms, and then compare that to letting the shoulders move with and in response to movements of your arms. Can you feel the difference?

Arm Shoulder Girdle Movement

Thinking about this a pianist comes to mind who complained of long-standing shoulder and arm discomfort while playing. Nothing had made a difference, and she had lived with that for a long time. After exploring how much her shoulder girdle can move the instruction became: “let your shoulders move when you bring your hands to the keyboard”. The result, so much relief she burst into tears.

This story illustrates how discomfort may be a consequence of simple misunderstanding about how things work. The BodyMinded process is to practise conscious cooperation with the way things work. This is sometimes stated as: Let everything move that needs to move in service of your activity.

Each article in this series will cover a specific example of BodyMinded thinking in practise, concluding with a general principle that applies to achieving and teaching good coordination as a musician. In this way I hope to assist you with your enjoyment and wellbeing in playing, and support those who are teaching others.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

1 For example, of respondents to an extensive survey of Australia’s 8 full-time orchestras “84% had experienced pain or injuries that had interfered either with playing their instrument or participating in normal orchestral rehearsals and performances” Musculoskeletal Pain and Injury in Professional Orchestral Musicians in Australia B. Ackermann, T. Driscoll, D.T. Kenny https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2012.4034

2 There is neurological research which suggests that the brain grows the neurological ‘map’ of the self to include the instrument, in that sense the instrument does actually become an ‘extension of the self’. Coding of modified body schema during tool use by macaque postcentral neurones A. Iriki, M. Tanaka, Y. Iwamura https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199610020-00010