Ondine Records, a member of the Naxos Group based in Helsinki, Finland, was founded in 1985 as an independent label. Since 2009, Ondine has featured renowned Finnish and international artists. Their award-winning recordings of contemporary music include works of composers Einojuhani Rautavaara, Kaija Saariaho, Magnus Lindberg, and Pēteris Vasks, as well as other present-day international artists. In 2023, Ondine won two Gramophone awards for their CDs of contemporary repertoire.

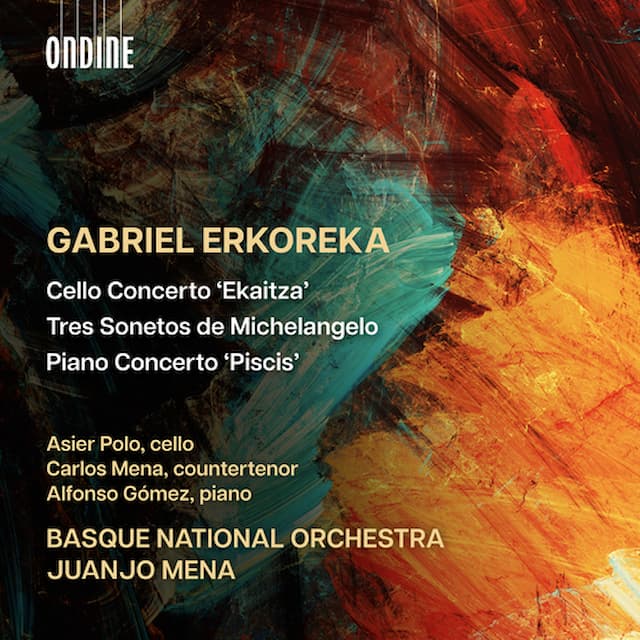

Gabriel Erkoreka

Ondine’s newest release in June 2024, features the Basque composer Gabriel Erkoreka—his Cello Concerto Ekaitza from 2012 performed by Asie Polo, cello; his Tres Sonetos de Michelangelo, from 2009 featuring Carlos Mena, countertenor; and the Piano Concerto Piscis (2021-2022) Alfonso Gómez, piano with the Basque National Orchestra, Juanjo Mena conducting.

Gabriel Erkoreka (b. 1969) is one of the leading composers of contemporary music from the Iberian Peninsula. Erkoreka studied composition with Michael Finnissy at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Since then, his works have been performed on several continents and at prestigious festivals. He received the National Music Award given by the Spanish Ministry of Culture in 2021 and he currently holds the post of professor in composition at MUSIKENE, the Higher School of Music of the Basque Country located in San Sebastián, Spain.

The music spans over a decade of the composer’s oeuvre.

The cello concerto Ekaitza which means tempest, is in three continuous movements. One could say the writing often features the soloist and the orchestra in conflict and, at other times with resolution. His orchestration, in keeping with the theme of a violent, raging, and windy sea, exhibits extreme sonorities and dramatic contrasts. In these works, the composer eschews transparency in favor of opaque, dense, and avant-garde lines.

The first movement begins angrily, with ponticello (bowing on the bridge for a rasping sound) and tremolo (very fast back and forth bow stroke “trembling” on the string), mainly in the lowest sonorities, and fortissimo. There is quite a bit of pizzicato with some snapping of the strings. The cello plays alone for a substantial portion of the introduction, occasionally punctuated by tuba, bass clarinet, some percussion, and a bit later, the harp. The movement is without a discernible rhythm and is seemingly aleatoric. The last minute of the movement becomes ghostly, echoing, the flute simply blowing air.

The second movement continues this eerie atmosphere with several repeated extremely slow glissandos in the cello (sliding on the string high to low.) But soon, he returns to a wrathful fortissimo and morphs into a cadenza that is virtuosic and melodic in places. It is impressively played. The orchestra enters with brazen, audacious writing, again without an evident pulse.

Gabriel Erkoreka: Cello Concerto “Ekaitza” – II. — (Aspier Polo, cello; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

Gabriel Erkoreka: Cello Concerto “Ekaitza” – III. — (Aspier Polo, cello; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

Asie Polo

The finale introduces a driving dance rhythm in the cello. It’s aggressive, so there is a great deal of forceful fortissimo attacks on the instrument, which takes a lot of stamina to perform. The last minute of the piece, a blaring tutti, is suddenly interrupted. The ghostly cello, playing slow, soft glissandos in microtones, returns and fades out, disappearing into the spheres.

I’d certainly like to see how the piece is annotated. The composer had to convey his intentions on paper and likely utilized unusual or new notations and explanations. Learning a piece like this, and rehearsing with the orchestra to put it together, must have been a daunting process for both the soloist, the orchestra, and the conductor.

The 3 Sonetos de Michelangelo are separated by two orchestral interludes; hence, the work is in five movements. The Sonnets, sung by countertenor Carlos Mena, are texts of Michelangelo Buonarroti that have been interpreted by other composers as well, such as Wolf, Britten, and Shostakovich. Erkoreka writes that the “first sonnet, {Sonnet XVIII} symbolizes sculpture through variations in density and volume, where the homogeneous– almost marble-like–body of the strings is carved through metallic percussions.” One can hear an anvil reflecting the text, “Only with fire can the blacksmith spread iron.” The composer calls for a type of stuttering on one note and fluctuations between pitches in the vocal line.

The percussive effects in the short orchestral interlude seem to imply sparks flying. In Sonnet XI the vocal line is accompanied by the winds and percussion featuring the tambourine and blocks. But the sonnet ends tonally. In the following slow Interlude, extremely high strings and winds enter for an eerie effect, but there are frequent and violent interruptions from the brass and percussion. Sonetto XXVII begins with the soloist alone, singing a cappella, almost beseeching, highlighting large intervals that reach for each other. The vocal line throughout is provocative, with leaps from very low to high frequencies, soft to loud dynamics, and moments of non-vibrato that create a melancholy effect, especially in this slow tempo. The piece ends abruptly, questioning and dissipating. Like the cello concerto, there is no discernable rhythm.

Gabriel Erkoreka: 3 Sonetos de Michelangelo – IV. Interludio secondo (François Cardey, cornet; Núria Sanromà, cornet; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

Gabriel Erkoreka: 3 Sonetos de Michelangelo – V. Sonetto XXVII (François Cardey, cornet; Núria Sanromà, cornet; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

The Piano Concerto is the most recent work on the recording. Erkoreka writes of the Piano Concerto, “Having been born under the sign of Pisces, and since piano is my instrument, with this title I intend to highlight in my first piano concerto a self-referential component linked to my own music, and especially to my previous piano works.” (album liner notes) Alfonso Gómez, is the dedicatee and performer.

There is no doubt the writing is bold and demanding for the soloist, as in this work too, the pianist traverses the entire range of the instrument, and every keyboard technique is utilized—trills, fast passage work, chords, leaps, ruthless staccatos, much of it in fortissimo. The first movement, dissonant, jarring, and harsh in places, ends abruptly. The second movement begins with the contrabassoon in murky, nebulous waters, with the piano entering with aggressive repeated chords. There is an extended cadenza that is brilliantly played. Strange sounds imitating wind interject, but there is no respite. The work explodes into the third movement. The ferociousness increases until it seems there is no more steam left, then once again, the composer ends in a pianissimo, fading out to nothing. One can only wonder if the Piano Concerto is a denunciation of what is happening in our time perhaps to the oceans and our climate.

In a recent article about Bartók, I discussed how some music, especially contemporary music, benefits from multiple hearings and some guidance. These three works may not be immediately accessible. The visual aspect of seeing these works in performance or in a video—how the soloists produce the unique sounds, seeing the conductor indicate where beats or emphasis might be, noting which instruments are playing to focus attention to the sonorities and different textures—would help listeners approach these complex pieces.

I admire the artists for what must have been an extraordinary commitment to learn these pieces.

Reflecting the angst of the times, Erkoreka’s music is full of vexation and indignation. At times, it’s coarse and caustic, while other stretches are brash, bold, thought-provoking, and ultimately brave.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Gabriel Erkoreka: Piano Concerto, “Piscis” – II. — (Alfonso Gómez, piano; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)

Gabriel Erkoreka: Piano Concerto, “Piscis” – III. — (Alfonso Gómez, piano; Basque National Orchestra; Juanjo Mena, cond.)