Stravinsky

Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 1 (1907)

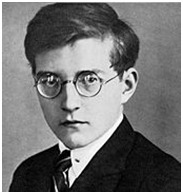

At age nine, Russian musician Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) was already a music prodigy. His parents took him to his first opera performance when he was five, only to find him singing several songs from the show the next day. His talent was soon discovered after several piano lessons with his mother, when he displayed perfect pitch and a remarkable musical memory. His unusual talent often encouraged him to pretend to play a piece from score, when in actual fact he was reproducing it from memory. Soon, the young Shostakovich was effortlessly playing the Haydn andante, Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album, Mozart and much more.

At age nine, Russian musician Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) was already a music prodigy. His parents took him to his first opera performance when he was five, only to find him singing several songs from the show the next day. His talent was soon discovered after several piano lessons with his mother, when he displayed perfect pitch and a remarkable musical memory. His unusual talent often encouraged him to pretend to play a piece from score, when in actual fact he was reproducing it from memory. Soon, the young Shostakovich was effortlessly playing the Haydn andante, Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album, Mozart and much more.

By the age of 13, Shostakovich had devoted his life to music. He studied composition and the piano during his secondary education at the Petrograd Conservatory. The Conservatory was then headed by composer Alexander Glazunov, who closely monitored his progress. His graduation piece First Symphony was so impressive that several conductors such as Bruno Walter and Leopold Stokowski had it premiered in Leningrad, Berlin, and Philadelphia. Shostakovich also made his first recording, earning him international acclaim. He soon gained favour with Russia’s new Leninist Government, who perceived him as a valuable political tool to influence new trends for the Revolution.

By the age of 13, Shostakovich had devoted his life to music. He studied composition and the piano during his secondary education at the Petrograd Conservatory. The Conservatory was then headed by composer Alexander Glazunov, who closely monitored his progress. His graduation piece First Symphony was so impressive that several conductors such as Bruno Walter and Leopold Stokowski had it premiered in Leningrad, Berlin, and Philadelphia. Shostakovich also made his first recording, earning him international acclaim. He soon gained favour with Russia’s new Leninist Government, who perceived him as a valuable political tool to influence new trends for the Revolution.

Shostakovich’s First and Second Denunciation

Unfortunately, the prodigy’s promising career was cut short as Joseph Stalin rose to power in the mid 1930s. While the 1934 premier of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District gained astounding acclaim upon its introduction, its success was halted after Stalin viewed the performance at the Bolshoi Theatre.

Apparently, Stalin thought the work contradicted with “correct Soviet form” and stormed out of the opera house just after the first act. Two days later, an article entitled ‘Muddle instead of Music’ appeared in the central Soviet newspaper Pravda condemning Lady Macbeth as “coarse, primitive and vulgar”. Even though Soviet music critics expressed their disagreement with the opinions expressed in Pravda, another article entitled ‘Ballet Falsehood’ attacking Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream was released. While the article accused Shostakovich for inaccurately displaying peasant life on the collective farm, it was really a means to punish him for exposing the realities of peasant life under Stalin’s regime, a topic considered too serious for public display.

What Stalin ordered to be published proved disastrous to Shostakovich’s reputation and creative output, as it prompted opera houses throughout the Soviet Union to cancel performances of his work, reducing his income by three quarters. Between 1936 and 1937, circumstances forced the composer to withdraw Fourth Symphony. He turned to conservative film music instead, as it was a genre free from personal expression and highly favoured by Stalin. The composer was quickly hailed by authorities as a true Soviet artist who had turned away from his previous ‘erroneous’ ways. Fourth Symphony was not performed until 1961, well after Stalin’s death.

What Stalin ordered to be published proved disastrous to Shostakovich’s reputation and creative output, as it prompted opera houses throughout the Soviet Union to cancel performances of his work, reducing his income by three quarters. Between 1936 and 1937, circumstances forced the composer to withdraw Fourth Symphony. He turned to conservative film music instead, as it was a genre free from personal expression and highly favoured by Stalin. The composer was quickly hailed by authorities as a true Soviet artist who had turned away from his previous ‘erroneous’ ways. Fourth Symphony was not performed until 1961, well after Stalin’s death.

Shostakovich with close friend Ivan Sollertinsky

Despite the efforts to conceal the true meanings of his works, several of Shostakovich’s subsequent compositions including Jewish Poetry still fell under Soviet censorship. He was condemned again in 1948 for formalism and was forced to repent in public. From then on, his works were officially banned.

The Adversity Continues

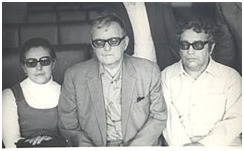

Dmitry Shostakovich (center) with his wife Irina and Azerbaijani composer Gara Garayev

A Russian stamp issued in memory of Shostakovich

“Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order.”

~ Dmitry Shostakovich, in a letter dated 1967

References:

Angotti, N. (n.d.). The Life and Music of Dmitri Shostakovich. Retrieved August 15, 2011, from University of Texas: http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/creees/_files/pdf/curriculum/CREEES-developed-units/shostakovich.pdf

Dmitri Shostakovich. (2011, August 10). Retrieved August 15, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Shostakovich#Personality

Dmitri Shostakovich. (2011). Retrieved August 15, 2011, from ClassicalNet: http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/shostakovich.php

Fay, L. E. (2000). Shostakovich A Life. Retrieved August 15, 2011, from The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/f/fay-shostakovich.html

Relationship between Dmitri Shostakovich and Joseph Stalin. (2011, August 14). Retrieved August 15, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relationship_between_Dmitri_Shostakovich_and_Joseph_Stalin#Lady_Macbeth_and_the_Pravda_articles