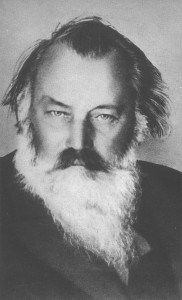

Credit: http://hhpromotionslondon.com/

The Brahms biographer Max Kalbeck, personally acquainted with the composer for almost two decades, reports that on 31 December 1890 he “found Brahms bare-chested in the middle of his study… incessantly pouring ice water over his head…His face had a purple complexion and his eyes were ablaze…When I asked what he was doing, he answered ‘I am so terribly hot.’… I reached for his hand, and felt his feverishly racing pulse. Having experienced the disease myself, I informed him that he was suffering from influenza. ‘Anything else wrong with me?‘ was his annoyed reply…. Although Brahms appeared in public the next morning, he looked pale, confused and tried to hide his weakness. Brahms attempted, with exaggerated jocularity and light-hearted demeanor to dismiss and downplay the extent of this second infection. Nevertheless, rumors about his impending demise circulated for several months throughout the Viennese press, which Brahms finally rebuked in May of 1891 with a paid notice that he had arrived at his summer residence in Bad Ischl in good health.

Nevertheless, within the very same week, Brahms also drafted and communicated his last will, generally referred to as the “Ischler Testament” to his publisher and friend Fritz Simrock. Brahms amended his testament in 1896, an alteration that caused twenty-two would-be heirs to emerge, some residing as far away as Philadelphia and Chicago. It took almost twenty years of legal uncertainty and wrangling before all the dust had finally settled. In 1891, however, Brahms insisted that the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde was to receive his books and his own and other musical autographs. Furthermore, he also settled the fate of his own unpublished compositions. He wrote, “I would like you to burn all the unpublished manuscripts I leave behind. I am now personally taking care of this task as best as possible so that you will find little on which to honor my request. I should be horrified to think that anything useless might be found.”

The most serious byproduct of Brahms’s influenza episode, however, was the composer’s insistence that he was going to permanently cease all compositional activity. The viral infections also served as the catalyst for Brahms to seriously question as to what kind of musical legacy he was leaving behind, and how history would, or better yet should, remember him. His way of exerting tighter control over this legacy manifests itself quite readily in the compositions that he allowed to reach the public after 1889. Although inspired by Richard Mühlfeld to explore the potential of the clarinet in his brand new chamber works op. 114, 115, and 120, Brahms began to selectively complete composition projects that he had been carrying in his portfolio sketchbooks, in some instances, for extended periods of time. This cleansing of his compositional palate saw the completion of his second String Quintet op. 111 and the extensive reworking of his “youthful indiscretion,” his synonym for the opus 8 Trio. The vocal quartets for mixed voices with piano accompaniment op. 112, three choral motets op.110, Eleven Choralvorspiele op. 122 and his thirteen Canons for women’s voices, op. 113 date conceptually, and some of them factually, from the 1850’s. The same might be said of the forty-nine “authentic” German folk songs and the fifty-one technical exercises for the piano, both published without opus numbers. The four serious songs op. 121 and the instrumental equivalents, the poetic piano-miniatures Opp. 116, 117, 118 and 119 form at once a carefully chosen natural extension and definitive closure of Brahms’s lifelong preoccupation with setting poetry to music. Brahms clearly had, as he communicated to Clara Schumann, come full circle as a composer.

The composer eventually did succumb to pancreatic cancer in 1897, and I’ll tell you all about this in our next episode. His first real brush with mortality, however, inspired Brahms to exercise tighter control over his musical legacy. He was determined to find a way of connecting his own personal legacy to that of German bourgeois cultural heritage. After 1889, Brahms only allowed for the publication of a compendium of genres, which were intimately connected with the nineteenth-century correlate of musical education or “Bildung.” As such, his final publications are therefore in equal measure part of the literary and musical culture of the educated classes, and approach the listener in an environment of conversational informality and devotional solemnity.