This week, Greek National Opera (GNO) in Athens is putting on the third performance of Nadia Boulanger’s only opera, La ville morte. Written in collaboration with her mentor, Raoul Pugno, the opera is only now in the 21st century, seeing its life on stage. Our current interest is because of the importance of Nadia Boulanger’s decades as the most influential music teacher of the 20th century. Pugno has largely been forgotten. This article and the next will trace the history of the opera and modern productions.

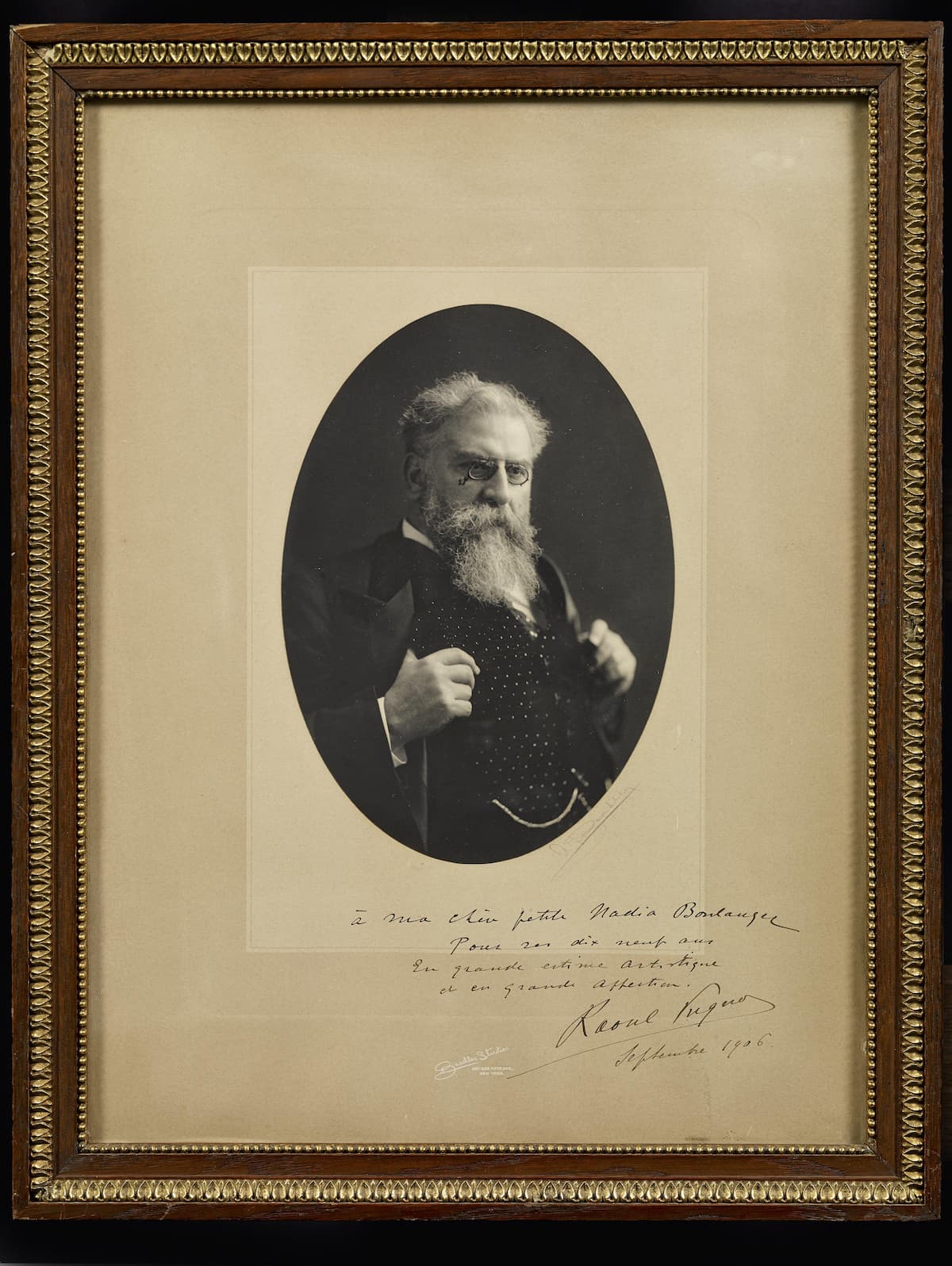

The opera was completed in 1913 and was written after Boulanger (1887–1979) had completed her studies at the Paris Conservatoire, while she continued to take classes there. She was working at the time with her mentor, the French composer Stéphane Raoul Pugno (1852–1914). As a pianist, he often played duets with both Saint-Saëns and the young Nadia Boulanger, and he encouraged her work, although there is some question as to the degree of their relationship. This photograph from Boulanger’s estate is of Raoul Pugno, given to her on her 19th birthday, inscribed ‘en grande estime artistique et en grande affection’. Another Pugno photo in her collection was dedicated to her as ‘une rare musicienne, un exquise camarade…’.

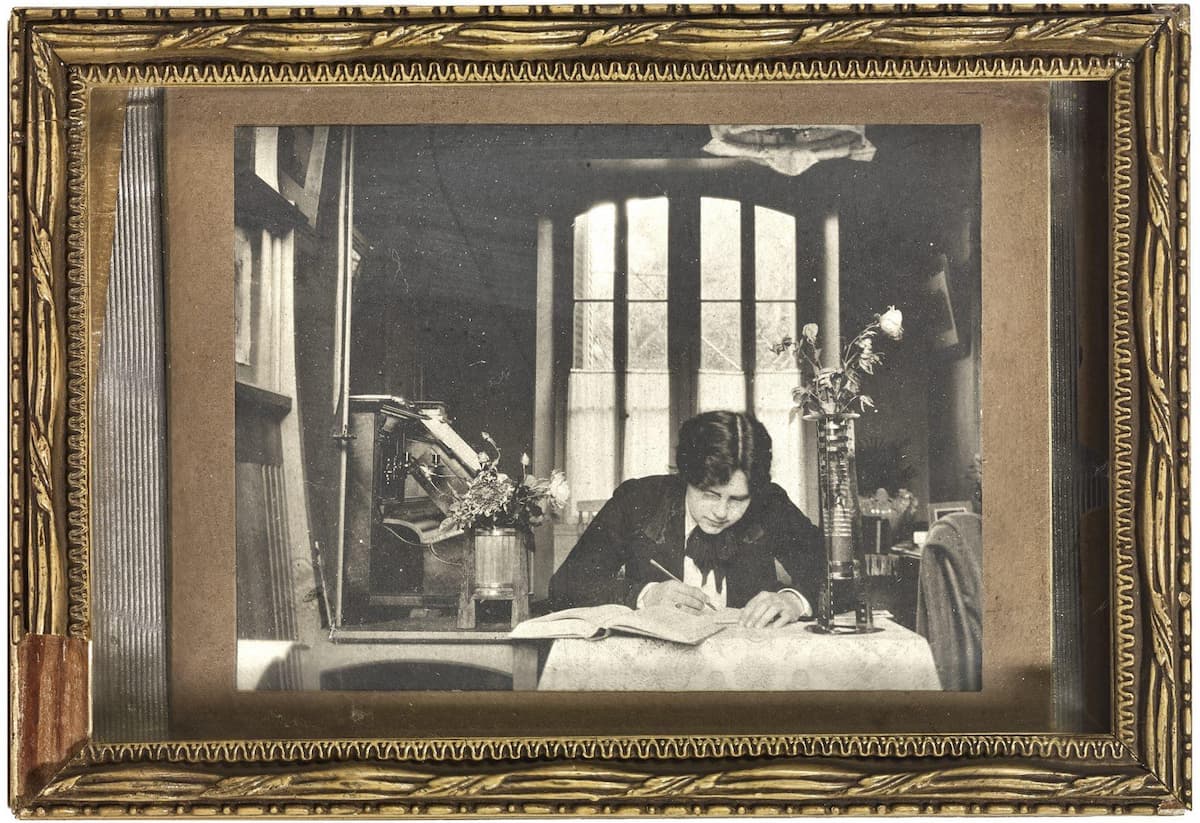

Nadia Boulanger, 1905–1906 (Paris: Collections du Cité de la Musée de la Musique)

Raoul Pugno, 1906 (Paris: Collections du Cité de la Musée de la Musique)

La ville morte is based on the 1896 play by Gabriele D’Annunzio, La cittá morta. D’Annunzio’s play had its Paris debut in French in January 1898, with Sarah Bernhardt in the role of Anna. D’Annunzio had written the play for his lover, the equally (in)famous Eleonora Duse, but the premiere went to her rival in France before she could give its Italian premiere in Milan in 1901. Pugno had prevailed upon his friend D’Annunzio to adapt his play for the opera libretto, with one result that the 5-act play is now a 4-act opera.

The collaboration between Boulanger and Pugno means that the only part of the opera that we know was truly written by Boulanger is the prelude, as it was written after Pugno’s death.

Although some scholars approach the work believing that Boulanger wrote the women’s parts and Pugno the men’s, the evidence doesn’t bear this out. Scholars cannot determine responsibility, except for noting that Boulanger’s contributions seem to be fully annotated with expression markings, and Pugno’s seem to have more adventurous harmonies. But, as a collaboration where the composers’ ages were so different, this isn’t unexpected. While they were working on it, Boulanger and Pugno would perform it together, Boulanger singing the women’s parts and Pugno the men’s.

The story is set in the excavations of the Greek city of Mycenae, an archaeological site. Léonard, an archaeologist, is leading the digging, aided by his younger sister Hébé (Bianca Maria in D’Annunzio’s original). Joining the siblings are Alexandre, a writer and poet, and his blind wife Anna.

The initial relationship is between Hébé and Anna. Hébé reads Sophocles’ play Antigone to Anna, and when she stops reading, blind Anna admires the tactile elements of Hébé, particularly the texture of her long hair. Hébé is too young to understand Anna’s feelings but it makes her happy. Alexandre arrives, having ridden across the dry country. Léonard enters with some of his discoveries from the site, lamenting that in finding the burial places of Agamemnon, Eurymedon, Cassandra, and others, buried with their golden masks, and their clothes and riches, their bodies instantly melted away, leaving only the physical objects.

End of Act I: Léonard (Joshua Dennis) shows Alexandre (Jorelle Williams), Anne (Laurie Rubin), and Hébé (Melissa Harvey) the gold objects he’s just discovered

In the second act, Alexandre reveals his love to Hébé and she recoils from him, thinking she hears the voice of Anna. Returning to the house, Anna senses Hébé’s emotional turmoil and decides, wrongly, that Alexandre and Hébé have become lovers.

In the third act, Alexandre presses Léonard to tell him why he has been so upset and driven. It’s driving a wedge between the two friends, and Léonard finally confesses that he’s in love with Hébé. When he returns to the house, Anna tells Léonard about her beliefs about Alexandre’s and Hébé’s relationship, and this drives Léonard even crazier. When he confronts Hébé with the story, she denies it, insisting that she is pure. This seems to calm Léonard, who then asks her to come out in the evening to meet him at the local fountain.

In the last act, to maintain his sister’s purity, Léonard drowns Hébé in the fountain and is discovered by Alexandre. They attempt to hide the body, and, in the D’Annunzio original, are discovered by Anna, who then regains her sight. In this version of the opera, Anna in the house regains her sight, apparently having sensed Hébé’s death.

Following Pugno’s death in Moscow in January 1914, there was a great desire expressed by Paris musicians to see La ville morte staged at the Opéra-Comique because so many wanted to hear Pugno’s last work. Plans moved forward for an Opéra-Comique production: the score was sent out by July 1914, the sets and posters completed (although they were approved by D’Annunzio in place of the deceased Pugno, rather than Boulanger), and the chorus was set to start rehearsal on 17 August 1914.

Unfortunately, August 1914 was also the date of France’s entry into WWI, and this meant all plans were suspended. After the war, nothing happened to get the work on stage. By the 1920s, Nadia Boulanger had made her career as a teacher, and, in fact, following the death of Pugno, Boulanger wrote no other large-scale works.

However, interest in the work rose periodically, and there were at least two attempts to get it staged. The history of the manuscript is one of bits and pieces. The prelude was completed after Pugno’s death. A manuscript copy of Act I, dated 6 September 1923, was found at the publisher Heugel’s and was the start of an attempt to stage the work at the Opéra-Comique, driven by inquiries started by D’Annunzio. Boulanger made revisions in the 1923 score but the staging at the Opéra-Comique for the 1923–24 season never happened. In 1946, Boulanger sent the piano score to her student Leonard Bernstein after he expressed an interest in staging the work, but that fell through as well.

No copies of the orchestrated versions are complete: acts one and three are still missing. To do a modern staging would require a great deal of work and it had to wait nearly a century for that to occur.

Find out more about the Greek National Opera production from “A Major Minor Opera: Nadia Boulanger’s La ville morte, The Performance“.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter