Michael Tippett

Tippett : A Child of our Time

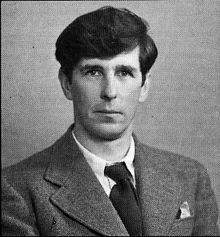

This man is not Tippett, but Sir Benjamin Britten. Britten was undeniably a remarkable musician – not just a composer, but a wonderful conductor and pianist too. His compositional technique was superlative, his musical voice powerful and individual. He wrote for the greatest musicians of his time, and for singers in every parish church. He produced great works in all genres – opera, oratorio, song, symphony, concerto, chamber music (though oddly no solo piano music of note). He was a patron of the arts in this country, founding the Aldeburgh Festival and the English Opera Group. It seems inconceivable that one could disagree with the verdict of Britten as by a distance the greatest British composer of the 20th century.

This is tough on Tippett. The two composers were good friends, with a high level of mutual respect and much in common – both were homosexual, for example, and both were convinced pacifists. Yet while Britten’s music since his death is performed around the world almost on a daily basis, performances of Tippett are much rarer. Even A Child of our Time, his most frequently performed work, is one of his earliest major pieces, and is perhaps unrepresentative of his mature style. His five operas, four symphonies, five string quartets and many other works are all but ignored in the country of his birth. There are some obvious reasons for this. A lot of his music is very difficult to play, with much of it gaining its energy and character from Tippett’s fantastic sense of rhythmic invention (demonstrated clearly in the early Concerto for Double String Orchestra). Whereas Britten frequently found inspiration in extra-musical sources, especially poetry, Tippett ‘s music is often abstract, and this combination of rhythmic complexity and formal integrity do make his works a harder listen that Britten’s.

Benjamin Britten

But Tippet’s relative unpopularity is certainly not universal. Towards the end of his life, while achieving relative success on British soil, he became a hugely popular figure abroad. His music was performed and received with enthusiasm in Zambia, and Australia, and he developed an important position in the musical life of America – he was twice invited to be composer-in-residence at the Aspen Festival, and Tippett fan clubs proliferated in America during the 1970s. Tippett was always keen to assimilate new ideas, and his relationship with other cultures bore considerable fruit in his own music, with late works such as the Third Symphony featuring American idioms like boogie-woogie and blues.

To me, this might well be part of the problem for British audiences trying to engage with Tippett. Britten’s musical and dramatic language is, in its own way, very British. His operas in particular are rife with characters closely linked with British life – Miles in The Turn of the Screw is the archetypal prep school boy, and the whole cast of Albert Herring is straight from the village lawns of middle-class England. Those two operas are significant in themselves, in that they both appropriate foreign texts (Henry James’ story was the basis for Screw, and Albert Herring is based on a novel by Maupassant) and turn them into resolutely ‘English’ works. The most popular of them all, Peter Grimes, is profoundly associated with England, most clearly in terms of its depiction of the Suffolk coast, but also with its depiction of British society – repressed and regressive, outwardly self-effacing but inwardly full of turmoil. Any outsider who threatens to break the cover of conformity (as Peter tries to do in the Church scene in Act II) be removed: in the words of the chorus themselves, ‘Him who despises us we’ll destroy’. Britten was in some ways such a character – much of his language and living habits stayed with him from his prep school days, and as a homosexual, he was in some ways as repressed as the characters of Grimes.

Tippett was the quite the opposite. A continental upbringing made him open to different cultures and ideas, and much of that made its way into his music. He was widely read, and was fascinated by Jung. His music and its influences are colorful, exultant and messy. A comparison of the two men’s first operas shows this clearly – as opposed to Grimes’ story of buttoned-up repression, Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage has a libretto which draws on mythology, oriental culture, Frazer’s The Golden Bough and many more. The closest companion work to it is probably Messaien’s Turangalila-Symphonie – both works, as well as sharing similar influences from oriental culture, are concerned simply with exultation, with celebrating life in all of its glorious complexity and diversity.

This might help to explain why Tippett struck such a chord with listeners outside his own country. It’s dangerous of course to stereotype about national characters, but I do think it’s true that his relaxation, his energy and his open glorification of love are perhaps much more in tune with European and American cultures than with British sensibilities. Being, as I am, a British musician sceptical about some of Britten’s achievements can lead to plenty of arguments. It is of course impossible to deny that he produced some wonderful music. But I have to confess that I find Tippett’s music, his sense of the joy of life, which flows through every bar of his music, utterly beguiling. It teaches us to celebrate love, to be interested in other cultures, in philosophy and ideas – essentially, to engage with and draw what we can from the world around us. Britten’s centenary year has begun – let’s hope that after that, we can begin to celebrate Tippett as the wonderful, life-enhancing artist he truly was.