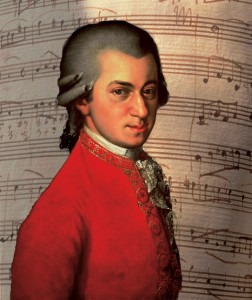

MOZART, W.A.: Serenade No. 10, “Gran Partita”

MOZART, W.A.: Serenade No. 10, “Gran Partita”

Sabine Meyer Wind Ensemble

Mozart’s Serenade K.361 has a lot of mystery surrounding it, generating many articles, thoughts and opinions (both scholarly and informal) with regards to its genesis and function. The work’s large scope gives it a fairly unique position within Mozart’s oeuvre, and within the classical repertoire in general. With the exception of a couple of other Serenades by Mozart (K. 375 and 388), and two by Richard Strauss (Opp. 4 and 7, replacing the basset horns with flutes), there are few other well-known pieces for these forces, and Mozart’s K.361 is arguably the most famous of the whole bunch. Some have proposed that the Serenade K.361 (commonly known as ‘Gran Partita’, although that title didn’t come from Mozart himself) was composed for Mozart’s own wedding, whilst others aren’t in agreement. What is true is that Serenades like Mozart’s K.361 were often composed for functions and outdoor parties, perhaps hence the lack of strings; wind instruments were (and still are, for that matter) considerably louder, something that makes sense given the supposed atmosphere in which Serenades were to be performed.

With that said, it isn’t a simple case of outdoor music = loud music. There are as many moments in K.361 which are tender, soft and beautiful as there are moments which are strong, forceful and energetic. With forces of 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 basset horns, 2 bassoons, 4 horns and double bass, there is scope for a large range of dynamic expression. The beauty of this piece is, though, that Mozart never over- or under-does it when it comes to texture. Despite the thick forces available, there is a clarity throughout which only Mozart can achieve through use of simple yet effective textural devices. (If you want a good bit of thickness, listen to the Strauss Op. 7, a perfect example of how to draw out and contrast the richest sounds of an ensemble of winds.)

‘Gran Partita’ begins with, as you might expect, a rather grand introduction, boldly stating block chords which are interspersed with a solo clarinet melody. This isn’t, however, a simple singable melody – that comes later. The clarinet’s interjections could be reminiscent of an operatic cadenza, with its expressive appoggiaturas and winding chromatic lines. The rest of the opening consists of a two-part texture, one of which is syncopated to give rhythmic momentum throughout the introduction. At one point, there are nine instruments playing, but only two lines are being played: the syncopated melody in the oboes, clarinets and basset horns, and the complementary accompaniment in the bassoons and double bass. A nice juicy dominant seventh chord gets us ready for the main Allegro movement, which is where our simple melody comes in. Stated in the clarinets, this two-bar theme forms the motivic basis for the whole of the second movement. Again, there are tutti moments where the clever use of texture helps to avoid an aural mushiness, such as before the exposition repeat. We’ve reached F major, and have a piano long dominant pedal (held on the note C) in the bassoons. The two clarinets play a short figure in thirds, then doubled by the basset horns and octave lower. Everyone comes crashing in a couple of bars later, but everyone plays either only the theme in thirds, or the dominant pedal, reducing a 13-part texture to a trio. Personally, this is one of the most exciting moments of the serenade, and it is given huge momentum by Mozart’s clever distribution of voicing.

There’s too much here to say in such a short space – there are so many moments in this Serenade at which you can marvel, whether it be for the clever harmonies, sparkling textures or beautiful melodies (the Adagio has been used many times in film and T.V. to particularly poignant effect). No one movement is better or worse than another, as they all contain an incredible economy of ideas and sounds.

So, seems like Mozart’s laid down the gauntlet. Will there be a Gran Partita of our time to come? It seems surprising that so little has been written for this combination, given that we have proof of what amazing music can be made with such a group.

More Blogs

-

Ten Shortest Composer Marriages in Classical Music Tragic love stories that shaped music history

Ten Shortest Composer Marriages in Classical Music Tragic love stories that shaped music history - How Accurate About Mozart and Salieri’s Rivalry Is the Film Amadeus? Discover what's fact vs fiction about Mozart and Salieri's rivalry

-

Five Must-See Klaus Mäkelä Performances: His Most Popular YouTube Videos Explore the controversial young conductor's best moments

Five Must-See Klaus Mäkelä Performances: His Most Popular YouTube Videos Explore the controversial young conductor's best moments -

How Clara Schumann’s Father Taught Her Piano Learn his approach to rhythm, chords, theory, and keeping students engaged

How Clara Schumann’s Father Taught Her Piano Learn his approach to rhythm, chords, theory, and keeping students engaged