Antonin Dvořák

In 1884/85, a wealthy patron of classical music named Jeanette Thurber set out to establish a uniquely American school of classical music composition. To accomplish this ambitious undertaking, she founded in quick succession the National Conservatory of Music of America and the American Opera Company. She initially contemplated to hire Jean Sibelius to head her newly founded conservatory, but eventually decided to engage Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904).

Dvořák, who had established a worldwide reputation as a composer utilizing nationalist musical elements and styles, was immediately fascinated by Native American and African-American music. The summer of 1893, when Dvořák spend his holiday with a Czech immigrant community in Iowa, saw the composition of three works — the Symphony “from the New World” and the “American” String Quartet and Quintet, respectively — compositions that are closely associated with his brief tenure in the United States. While the respective influences of spirituals, Creole tunes, Native American dances and literary/musical devices — including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha — are still open to interpretation, Dvořák unmistakably issued a clear challenge to American composers to find a distinctive American musical voice. He published his thoughts in an essay entitled “Music in America,” which appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in February 1895. “My own duty as a teacher is not so much to interpret Beethoven, Wagner or other masters of the past, but to give what encouragement I can to the young musicians of America…This nation must assert itself, especially in the art of music. When no large city is without its public opera house and concert hall and without its school of music and endowed orchestra, where native musicians can be heard and judged, then those who hitherto have had no opportunity to reveal their talent will come forth and compete with on another till a real genius emerges from their number, who will thoroughly represent this country.”

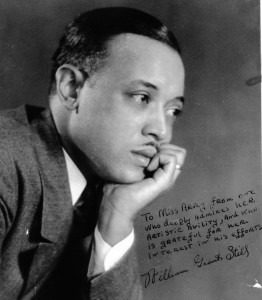

William Grant Still

Symphony No. 1, “Afro-American” (1969 revision)

William Grant Still

A number of students took up Dvořák’s challenge, among them Herny T. Burleigh, who published a collection of spirituals arranged in an art music style in 1916. William Marion Cook drafted an opera on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Florence Price published a symphony remarkably similar to Dvořák’s New World. However, it was William Grant Still who most prominently rose to answer Dvořák’s call. In his pioneering musical career, Still composed almost 200 works in a wide variety of genres, and all inspired by spirituals, African-American work songs, ragtime, blues and jazz. In all, he composed eight operas, with Troubled Island performed by the New York City Opera in 1949, and Bayou Legend premiered on national television. He also wrote symphonic poems, suites, ballets, chamber music and various songs. His best-known work, the Afro-American Symphony composed in 1930, received performances by the Berlin Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra and the BBC Orchestra, respectively. Remembering Dvořák’s words, Still writes, “I knew I wanted to compose a symphony, I knew that it had to be an American work; and I wanted to demonstrate how the blues, so often considered a lowly expression, could be elevated to the highest musical level.” Scored in four movements, each movement not only features a subtitle, they also correspond to verses taken from poetry by Paul Laurence Dunbar, written in African-American dialect. The third movement, for example, features the lines “An’ we’ll shout ouah halleluyahs, On dat mighty reck’ning day!” Frequently referred to as the “Dean” of African-American composers, Still received honorary degrees from Wilberforce University in 1936, Howard University in 1941, Oberlin College in 1947, Bates College in 1954, University of Arkansas in 1971, Pepperdine University in 1973, Peabody Conservatory of Music in 1974, and the University of Southern California in 1975. Although George Gershwin premiered his Rhapsody in Blue — the first-ever symphonic work to bridge the gap between Classical and Popular music in 1924 — Still’s symphony “is firmly rooted in his personal African-American heritage.”