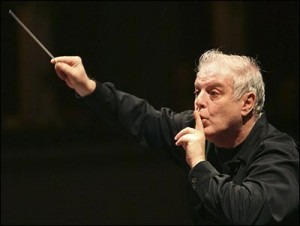

The extraordinarily rousing power of music is a force that, as any other, can be used for good or evil. Daniel Barenboim’s recent concert in Gaza City has re-affirmed the positive impact that music can have in politics. Barenboim led an orchestra of two dozen musicians from Europe’s best orchestras playing in a cultural centre. The programme was Mozart: “A little night music” and the G Minor Symphony. The macro-political ramifications of this event are remarkable: it required a special opening of the border at Rafah by Egypt, authorisation by Hamas and a logistical work of art by the United Nations, under whose auspices the concert was given. As Michael Kimmelman reported in the International Herald Tribune (‘A musical gift to Gaza’ 6/5/2011), the concert was an extraordinary sign of hope in the region: “our job is to bring things in and out of Gaza, but we have never brought music” said UN official Filippo Grandi.

The extraordinarily rousing power of music is a force that, as any other, can be used for good or evil. Daniel Barenboim’s recent concert in Gaza City has re-affirmed the positive impact that music can have in politics. Barenboim led an orchestra of two dozen musicians from Europe’s best orchestras playing in a cultural centre. The programme was Mozart: “A little night music” and the G Minor Symphony. The macro-political ramifications of this event are remarkable: it required a special opening of the border at Rafah by Egypt, authorisation by Hamas and a logistical work of art by the United Nations, under whose auspices the concert was given. As Michael Kimmelman reported in the International Herald Tribune (‘A musical gift to Gaza’ 6/5/2011), the concert was an extraordinary sign of hope in the region: “our job is to bring things in and out of Gaza, but we have never brought music” said UN official Filippo Grandi.

Political hope, nevertheless, comes and goes. As I write this piece, the first pages of international news websites tell me that fresh violence has erupted in Israel’s borders with the Palestinian territories, Syria and Lebanon. Barenboim’s concert itself had an abrupt ending after the UN received a threat from an Islamic extremist group in Gaza.

But these depressing developments do not, in my view, diminish the concert’s impact or the importance of cultural diplomacy. Because despite the undeniable macro-political implications of the concert which I have mentioned above, what touched me the most about the reports I read of the concert was the micro-scale impact of the music on the individual audience members. This was best summed up by Jawdat Khoudary, the founder of the cultural centre that hosted the concert; “for one hour or so we listen to music like the rest of the world. It’s an acknowledgement that we are normal people, that our interests are the same as anyone else’s in the world, that our dreams are the same, and that we want to create beauty again in Gaza” (in the IHT piece).

This comment on the unifying power of music, not in the large international sense, but in the individual human dimension, reminded me of Dag Hammarskjold’s thoughts on the importance of music. When he was Secretary-General of the UN (1953-1961), he promoted regular musical concerts at the UN with famous orchestras and musicians (including Pablo Casals, at a time when he was a persona non grata in the United States). Hammarskjold also instituted a tradition of a UN Day Concert (24 October), at which the last movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is always played. He liked the link the development of the musical themes in the 9th with the development of the international framework of law and diplomacy that culminated in the UN. Introducing the 1960 UN Day Concert, he noted;

This comment on the unifying power of music, not in the large international sense, but in the individual human dimension, reminded me of Dag Hammarskjold’s thoughts on the importance of music. When he was Secretary-General of the UN (1953-1961), he promoted regular musical concerts at the UN with famous orchestras and musicians (including Pablo Casals, at a time when he was a persona non grata in the United States). Hammarskjold also instituted a tradition of a UN Day Concert (24 October), at which the last movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is always played. He liked the link the development of the musical themes in the 9th with the development of the international framework of law and diplomacy that culminated in the UN. Introducing the 1960 UN Day Concert, he noted;

When the Ninth Symphony opens we enter a drama full of harsh conflict and dark threats. But the composer leads us on, and in the beginning of the last movement we hear again the various themes repeated, now as a bridge towards a final synthesis. (…) On his road from conflict and emotion to reconciliation in this final hymn of praise, Beethoven has given us a confession and a credo which we, who work within and for this Organisation, may well make our own. (in To speak for the world: speeches and statements by Dag Hammarskjold).

Although Hammarskjold recognised that the UN was still far from the international synthesis that its Charter envisages, he stressed that the world had come a long way from the dark themes of the first and second movement. How true his words ring today! I have commented on the dialectical structure of Beethoven’s symphonies before. This narrative, although it finds resonance in the large-scale international scenario, has the biggest impact when it hits individuals, transforming our perspective of ourselves and our relationship with the world around us, as Mr Khoudary noted.

Vaclav Havel called this “living in truth” – the affirmation of our own self, free will and independence not through large-scale political action, but by individual day-to-day actions. The audience members in Barenboim’s concert lived in truth performing those small acts that most of us take for granted (getting dressed up, going to a concert hall, finding one’s seat, waiting for the orchestra to tune their instruments…). Without such small-scale developments, large-scale politics would be as meaningless as an orchestra without its players.

Related video:

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, 4th Movement

Photo credit: operachic.typepad.com, britannica.com