In last week’s article, ‘Music and Graphics,’ we dove into the exciting realms of possibility opened up by “graphic scores” – musical compositions that are notated in nontraditional, visually expressive ways. After a whistlestop tour through the nascence of graphic scoring, centring on the work of composers like Morton Feldman and John Cage in the 1950s, we considered a variety of scores, looking at what each unique approach brought to the table. In that article, the narrative may have set up graphic scores as a kind of utopic tool, able to facilitate expressions of concept, self, and sound in astonishing ways. In this week’s article, we shall bring the conversation ever so slightly back down to earth: by walking through some of the realities – and limitations – of graphic scores.

Firstly, although graphic scores have been around for over seventy years, the infrastructures of classical music still struggle to make adequate provisions for their existence. These works are often jointly visual and sonic works of art, and yet it is rare that scores are printed in the programme, displayed in galleries, or otherwise treated in a way that respects and showcases the work’s visual component. As such, visual detail and innovations thought up so carefully by the composer are seen only by the conductor and performers, and a great chunk of the meaning and craft of the work is not properly conveyed to those receiving it.

Perhaps because of this lack of institutional recognition, there is general distrust and lack of awareness surrounding visual scores, especially for those unfamiliar with them or not embedded in so-called new music circles. One of my own compositions, people, being, made in collaboration with a choreographer and dance group, used graphic techniques in order to allow for greater synchronisation with the dance. After the premiere, the father of one of the performers – himself a musician – said, “That’s not how you write music!” in response to his daughter showing him a copy of the score.

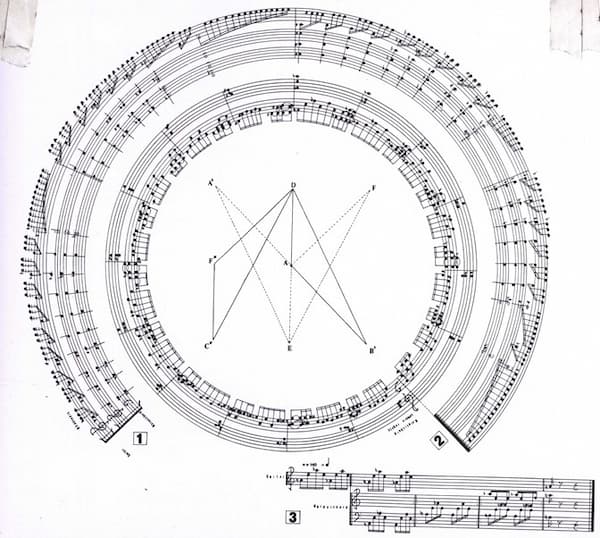

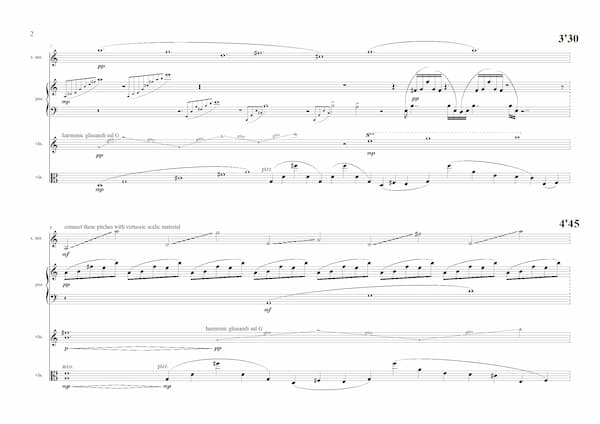

Siri Livingston: people, being

Siri Livingston: people, being

Surprisingly, I didn’t actually find this offensive. He was simply expressing a very well-engrained view of the role of the composer, one that I haven’t entirely shaken off myself: that the composer is, first and foremost, someone who writes down notes to be played in a very specific way, with every minutiae of dynamics and expression put to paper, leaving nothing ambiguous or up to chance. This pushback against open scoring and graphic notation could, I believe, be lessened in any number of ways, particularly through music education. For one only has to work from a graphic score once or twice – with fellow performers or alone – to wrap one’s head around how these methods open up new possibilities for music-making.

However ethereal and magical music can sometimes seem, the reality of musical activity is that it depends on people, who themselves are subject to economic reality. As such, the topic of graphic scoring also raises questions of expense, time, and achievability. The time of professional musicians is inherently expensive due to the years spent perfecting their technique. While many a composer might enjoy using graphic elements in their student days, the demands of professional life may necessitate using traditional notation – simply so as not to waste precious rehearsal time where opportunities and schemes for composers are always highly competitive. Christopher Fox, a composer working in the UK, describes this in his chapter on notation for the Cambridge Companion to Composition:

For a host of economic and aesthetic reasons, British musicians and promoters favour music that can be prepared for performance quickly. Consequently, the visual presentation of the music is expected to be as straightforward as possible; five minutes spent in explaining an unusual notation to a performer is five minutes of expensive rehearsal time lost. I soon decided that the notational experiments that had been a feature of many of my student scores would have to be sacrificed, at least temporarily, on the altar of affordability. This Faustian pact seemed unavoidable if I wanted professional musicians in Britain to play my music.

However, all is not lost – even Fox’s scores from this era are visually striking, and he still found ways to experiment with notation by enriching or impoverishing different levels of notational elements so as to subtly guide performers towards what he thought was the “heart” of the piece.

Nonetheless, it’s hard to deny – graphic scores often require the conductor and entire ensemble to spend time studying the score just to figure out how it works, which is costly. Furthermore, musicians spend years honing their muscle memory in response to traditional notation (as any irritated performer will tell you if confronted with an incorrect clef or notation in a workshop!), and graphic scores often don’t make use of this by abstracting notation. That being said, graphic scores can be so immediately visually striking and intuitive that they may make up for the lack of muscle-memory association.

Finally, on the level of preference and aesthetic tendencies, some performers simply prefer normal scoring and don’t respond well at all to graphic elements. Graphic scores very rarely specify exactly which notes to play and in what order, thereby necessitating some level of improvisation, which is something classical musicians are not trained to do. As such, any composer thinking of using graphic notation would do well to get to know the intended performer or ensemble, ensuring that they have the confidence and openness to give graphic notation a go. These scores also seem particularly well suited to low-pressure, group-devising settings.

Where does all of this leave us? We’ve seen how exciting, striking, beautiful, playful, and evocative graphic scores can be. We’ve also considered the economic and practical reality of using them and how audiences and performers alike may react to having one placed in their lap or on their music stand. It seems, then, that visual scoring is a valuable tool in the composer’s toolbox, one that may even form the bulk of a composer’s practice. Even so, seeing as graphic scoring is not the norm or default; it would be wise to be thoughtful about the context and way in which it is used.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter