The story of Orpheus and Euridice is one of the early stories told in opera. From the first operas in 1600 by Caccini and Peri to the 21st century, the story of the musician and his lost love was central to musical writing.

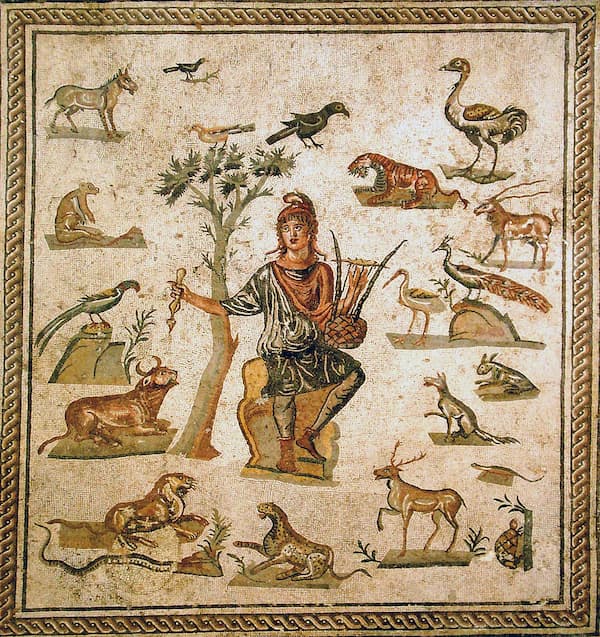

In Greek mythology, Orpheus was a legendary musician who played the lyre. He was also a poet, and the stories about him say that he could charm all living things, as in this Roman floor mosaic.

Orpheus surrounded by animals. Ancient Roman floor mosaic from Palermo (Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo) (Picture by Giovanni Dall’Orto)

He marries Euridice, but shortly afterwards, she is bitten by a serpent and dies. Orpheus vows to go to the Underworld to retrieve her and it is his wonderful musical abilities that permit him to cross the river Styx in Charon’s boat and persuade Hades to return his wife. Hades agrees, as long as Orpheus does not turn his head to ensure she’s actually following him. Orpheus succumbs to his curiosity and loses Euridice again, this time forever.

For opera composers, there are two storylines: one that ends with Orpheus’ death upon returning from the Underworld and a later one where his transgression is forgiven, and Euridice is returned to him. In the opera, the first storyline generally has a notable aria when Orpheus hears of Euridice’s death, and the second storyline has its notable aria at the end, just before Euridice is returned to Orpheus; it is the beauty of his song that persuades the gods to be kind.

The first operas, by Giulio Caccini and Jacopo Peri, were both written in 1600, although Caccini’s didn’t get a performance until 1602. Both operas have a big aria when Orpheus learns of Euridice death. Both operas are set to the same libretto by the poet Ottavio Rinuccini. Orpheus’ lament, Non piango, e non sospiro (I do not cry and I do not sigh), is set by both composers as a cry to the gods. Peri’s aria continues with his friends commiserating at his loss and then accompanying him so he doesn’t kill himself. This is an important addition to the Orpheus story because critics of the early mythological tale saw Orpheus as a coward for not killing himself immediately to join Euridice in death but rather traveling to the Underworld to get her back alive.

Giulio Caccini: L’Euridice (ed. M. Pollio and R. Alessandrini): Scene 2: Non piango, e non sospiro (Furio Zanasi, Orfeo; Concerto Italiano; Rinaldo Alessandrini, cond.)

Jacopo Peri: Euridice – Scene 2: Non piango e non sospiro (Olivier Lallouette, Orfeo; Joseph Cornwall, Arcetro; Françoise Masset, Dafne; Bruno Karl Boes, Tirsi; Arts Baroques, Les; Mireille Podeur, cond.)

Caccini and Peri aside, the most famous of the early Baroque settings is that by Claudio Monteverdi. Written in 1607 to a libretto of Alessandro Striggio, Monteverdi’s opera has a show-stopper in Orpheus’ lament: Tu sei morta, mia vita, ed io respiro? (You are dead, my life, and do I still breathe?). The aria starts with Orpheus in shock, slowly speaking about his situation. He questions why she has gone and why he’s still breathing. Soon, however, he resolves to bring Euridice back from the deepest abyss (and the music descends to match his lines). It ends with him saying farewell to the earth, the heavens, and the sun, with the musical line rising at each ‘addio’ before sinking in the final farewell.

Monteverdi: L’Orfeo with Marc Mauillon as Orfeo and Luciani Mancini as Euridice (in white clothes), 2021 (Paris, Opéra Comique)

Claudio Monteverdi: L’Orfeo – Act II: Tu sei morta, mia vita, ed io respiro? (Julian Prégardien, Orfeo; Les Epopées; Stephane Fuget, cond.)

This is a setting that’s indicative of both Monteverdi’s skill in word painting, where the music matches the motion of the text, and of how arias would continue to progress, being static sections where resolutions are made but no action taken. In Monteverdi’s time, the chorus moves the action on, eventually, that will be left to the recitatives.

The next great setting of the story happens in the 18th century when Christoph Willibald Gluck, using a libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi, writes his Orfeo ed Euridice. This 1762 opera is the first of Gluck’s ‘reform’ operas, where stupidly complex plots and even more complicated music were replaced by a simpler story and music. Gluck’s opera is one of the happy endings, and so it is Orpheus’ aria in Act III that holds the place of importance. Che farò senza Euridice? (What will I do without Euridice?) is Orpheus’ suicide aria until Amore intercedes to restore Euridice to him, giving us a happy ending.

Gluck’s setting is simple and effective, rising at the penultimate line to appeal to the heavens.

Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice with Stephanie Blythe as Orfeo and Danielle de Niese as Euridice (bottom left), 2009 (Met Opera) (photo by Ken Howard)

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice – Act III Scene 1: Aria: Che faro senza Euridice? (Jakub Józef Orliński, Orfeo; Il Giardino d’Amore; Stefan Plewniak, cond.)

Fernando Bertoni’s 1776 opera Orfeo ed Euridice, also uses Calzabigi’s libretto. This setting is more dramatic than Gluck’s and shows by contrast how Gluck’s simpler style was more effective in its setting. However, this is really about different markets. Gluck’s opera was for Vienna, whereas Bertoni’s was for Venice. Bertoni’s setting merges galant style with Italian opera seria, and serves its audiences’ need for decorated arias. What’s interesting is that both operas had the same Orfeo, the alto castrato Gaetano Guadagni.

Jean Baptiste Corot: Orfeo ed Euridice in the Underworld, 1861

Fernando Bertoni: Orfeo ed Euridice – Act III Scene 1: Arioso: Che faro senza Euridice (Vivica Genaux, Orfeo; Lorenzo Da Ponte Ensemble; Roberto Zarpellon, cond.)

Other settings of the Orpheus myth include Johann Joseph Fux’ setting of Orfeo ed Euridice for the birthday of his patron, Emperor Karl VI, in 1725 and revived it in 1728. This chamber opera includes as an aria, Rondinella che tal volta, where Euridice compares herself to a swallow (rondinella) that has been set free and to a wandering stream on her trip up from the Underworld.

Johann Joseph Fux: Orfeo ed Euridice: Rondinella (Elizabeth Dobbin, Euridice; Le Jardin Secret)

Around 1735, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi set Orfeo as a chamber cantata for soprano, strings and basso continuo with two accompanied recitatives and two arias.

Frederic Leighton: Orfeo ed Euridice, 1864

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi: Orfeo (Cantata) – Aria: Euridice, e dove, e dove sei? (Julia Faulkner, soprano; Camerata Budapest; Michael Halász, cond.)

The story of Orpheus also shows up in Francesco Cavalli’s 1643 opera Egisto, where the two lovers, Egisto and Clori, have been captured and separated by pirates. By Act III, the lovers are reunited, but now Egisto is raving madly, declaring that he is Orpheus and demanding the return of his Euridice. By the end of the scene, he recovers his senses and recognizes Clori, and there is a happy ending. By using Euridice as his reference point, Egisto is comparing himself to one of the great lovers of the mythological world – ready to face everything to have his love returned.

Attributed to Paul Duqueylar: Orfeo (Private collection)

Francesco Cavalli: Egisto – Act III, Scene 9: Rendetemi Euridice! (Gloria Banditelli; Roberto Abbondanza; Gianluca Belfiori Doro; Mario Cecchetti; Rosita Frisani; Mediterraneo Concento; Sergio Vartolo, cond.)

Another 18th century setting is by the English composer William Hayes. He set the story not as an opera but as an ode. It was written in June 1735 as an examination piece for his bachelor’s degree in music at Oxford. William Hayes’ setting of the Orpheus story doesn’t have a lament for Orfeo, but rather Euridice’s farewell to Orfeo. Following Orfeo’s fatal look back, Euridice tells him to go back to the surface, and they will meet in the future.

Ary Scheffer: Orpheus Mourning the Death of Eurydice, 1814

William Hayes: Orpheus and Euridice – Aria: Thy vain pursuit fond youth (Ulrike J.Hofbauer, Euridice; Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Hayes Players; Anthony Rooley, cond.)

The work ends with a duet for Euridice and Orfeo, With streaming eyes and throbbing heart, as they part until they meet again below’.

Enrico Scuri: Euridice recedes into the Underworld

William Hayes: Orpheus and Euridice – Duet: With streaming eyes (Daniel Cabina, Orfeo; Ulrike J. Hofbauer, Euridice; Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Hayes Players; Anthony Rooley, cond.)

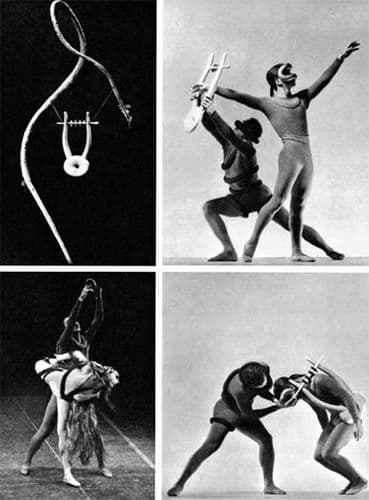

As a point of inspiration, the mythological story of Orpheus and Euridice gave composers over the centuries a way to depict love and loss, determination and regret in one tidy package. It wasn’t only 17th- and 18th-century composers who set the tale, but also composers such as Stravinsky, in his 1948 ballet Orfeo, with costumes by Isamu Noguchi and choreography by George Balanchine.

Isamu Noguchi’s Orfeo

Harrison Birthwhistle wrote The Mask of Orpheus in 1986, and Missy Mazzoli created her ballet Orpheus Alive in 2019. Turning to focus on the woman’s side, Matthew Aucoin wrote his opera Euridice in 2020; it received its Metropolitan Opera premiere in 2021.

The Metropolitan Opera Presents: Eurydice (Trailer)

For one story to have inspired composers for over 400 years is an achievement…or an indication of how important the story is to Western civilisation.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter