Deeply grounded in the entire spectrum of Chinese heritage—including folk, philosophical, and spiritual ideals—contemporary Chinese composers eagerly encode their experiences and convictions in music. Embracing musical diversity alongside a deep reverence for cultural traditions and a youthful exuberance for progress has established a thriving and living tradition of contemporary Chinese music.

Ye Xiaogang

Among China’s most active and most famous composers is Ye Xiaogang (b.1955). Born in Shanghai, he first studied at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing before furthering his studies at the Eastman School of Music in the United States. Ye Xiaogang is particularly known for his seamless integration of Chinese and Western styles, and his piano concerto Starry Sky premiered at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. He is the recipient of numerous prizes and awards, and his recording catalogue includes symphonic works, chamber music for various instruments, stage works, and a substantial variety of imaginative film scores. Intimately connected with the flourishing cultural scene of China, Ye’s music features exquisite textures, beautiful melodies, and refined orchestration throughout.

Ye Xiaogang: The Macau Bride Suite, Op. 34 (Mingyan Liu, mezzo-soprano; Macau Youth Choir; Macau Orchestra; Jia Lü, cond.)

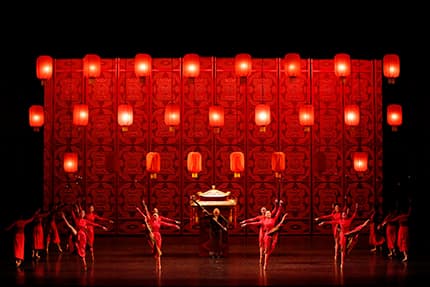

For the opening ceremony of the 12th Macao Arts Festival in 2001, writers, producers, and performing artists collaborated to produce a spectacular dance drama entitled “Macao Bride.” Utilizing colorful sets, lavish costume designs, and virtuoso dance choreography, the production told the story of a Portuguese girl and her Macanese suitor, all set in 17th century Macao. Ye Xiaogang was commissioned to provide the musical score, and the production premiered to great acclaim in 2001. A year later, the composer extracted two suites from the 4 acts of the ballet for concert use. The overture suggests the dangers of the sea, and we are introduced to the prosperous city of Macao. A Portuguese ship loaded with treasures sails for Europe, and in Belém, the Chinese sailor meets Maria do Mar. They fall in love and sail for Macau. The couple survives a storm and an attack and abduction by pirates, but are finally reunited and married in Macau.

Zhao Jiping: Moments Musicaux of the Silk Road (Shanghai Symphony Orchestra; Long Yu, cond.)

Zhao Jiping

Zhao Jiping is one of the most active Chinese composers on the international stage. One of the foremost composers in China, he uniquely established a style and a national and cultural spirit that are unquestionably Chinese. It is hardly surprising that he was honored as “a Professional with Outstanding Contributions to the Country.” A prolific composer, Zhao is particularly active in the film and television industry, having composed music for numerous films and television dramas. In fact, he has won countless awards at home and abroad, and the US, UK, and France biographical documentary “Music for the Movies: Zhao Jiping” was released globally in 2017. As a composer, Zhao is most comfortable in the symphonic realm. He has created countless symphonic poems, symphonies, and solo concertos for Western and Chinese instruments. His works reflect a wide range of interests and musical tastes inspired by growing up in Xi’an on the Silk Road. “It is the link between Chinese civilization and the way to Europe,” and Zhao’s music frequently references the Silk Road. His musical impressions of the Silk Road are primarily rooted in folk music, but they do incorporate modern techniques and perspectives as well.

Zhang Qianyi: “Yunnan Capriccio” (Beijing Symphony Orchestra; Lihua Tan, cond.)

Zhang Qianyi

Born in Shenyang, in China’s Liaoning province, Zhang Qianyi undertook advanced studies in composition at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music under the direction of Chen Gang, Sang Tong, and Shi Yongkang, and graduated in 1984. His neo-romanticist style of compositions produced a number of important works, and his substantial portfolio of compositions in a variety of different genres includes symphonies, ballet music, chamber music, dance music, and music for television and film. Over a period of 6 months, Zhang extensively toured Yunnan province, located in southwest China. He recorded and transcribed local folk music traditions from this thriving melting pot of rich local cultures and traditions. In the end, he musically encoded his experiences by composing the orchestral suite “Yunnan Capriccio.” The rich folk music traditions of Yunnan province also furnished the inspiration for Shen Chuanxin’s delightful “Yunnan Suite” for solo piano.

Shen Chuanxin: Yunnan Suite (Kwok Kuen Koo, piano)

Xian Xinghai, 1922

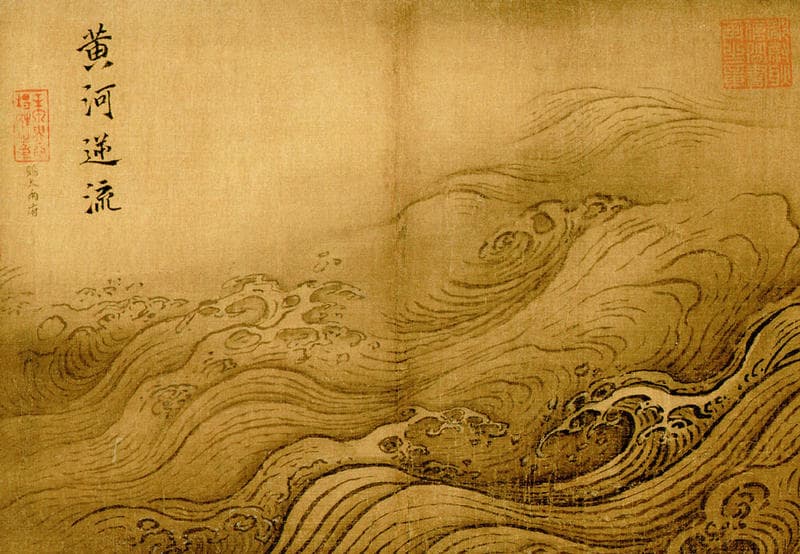

The great rivers of this world have spiritually highlighted the paradoxical relationship between eternity and change. As metaphors for life itself, they simultaneously underscore all that is timeless and ephemeral in human experience and existence. Because rivers sustain life by renewing the fertility of the land, poetry, folklore, and music have long emphasized their purification and cleansing properties. Vested with enormous spiritual significance, rivers have given rise to temples, cities, and civilizations, but they have also been used as material pathways for trade, the migration of people and ideas, and as natural or conceptual borders between countries. The Yellow River, considered since ancient times “the cradle of Chinese civilization,” has numerously given rise to poetic and musical depictions and interpretations. The Yellow River Cantata by Xian Xinghai (1905-1945), composed during the tumultuous years of the Japanese Invasion, quickly became a national musical epic. By using traditional folk melodies as symbols of Chinese defiance against the invaders, Xian fashioned a composition that quickly shaped a Chinese national identity. In 1969, this Cantata reemerged as a four-movement piano concerto entitled the “Yellow River Piano Concerto.”

Yellow River

The Yellow River Piano Concerto (Jie Chen, piano; New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; Carolyn Kuan, cond.)

The atmospheric “Prelude: The Song of the Yellow River Boatman” provides a vivid musical depiction of the untamed strength and power of the Yellow River. After a brief orchestral introduction, which borrows chromatic gestures from the “Eight Model Plays” of the Cultural Revolution, the soloist performs rapid arpeggiation spanning the entire range of the keyboard. This wave-like momentum in turn, gives rise to the quotation and subsequent virtuosic development of the “Song of the Yellow River Boatmen.” Originally sung by a heroic tenor, the melody of the “Ode to the Yellow River” is presented as a lush cello tune. Depicting the calm and picturesque landscape surrounding the Yellow River, this second movement provides a soothing musical hybrid that intermingles a late Romantic orchestration with pentatonic passages of nationalist flavour. A dizi and harp duet initiates the movement entitled “The Yellow River in Anger.” Initially, this tune provides a musical allusion to the Butterfly Lovers’ Concerto, before the “Ballade of the Yellow River” and the “Lament of the Yellow River” musically fend off all foreign invaders. The concluding movement, “Defend the Yellow River,” sparkles with patriotic tunes and the anthem of international socialism, combining musical methodologies borrowed from the West with source materials originating in China.

Zhao Song Ting: “Scenes of the Wu River” (Song-Ting Zhao, dizi; Shanghai Orchestra; Peng Cao, cond.)

Zhao Song Ting

The Chinese dizi bamboo flute player Zhao Song Ting was born in Dongyang county, Zhejiang province in 1924. Initially he trained as a teacher, but furthered his education in both Western and Chinese music in Shanghai. He frequently featured as a dizi soloist and was active as a composer and arranger of music for this instrument. He concentrated on the development and refinement of dizi design, and he passed on his knowledge to several generations of students. In addition, he also published two sets of essays and teaching materials for his instruments. His musical craft and imagination are beautifully encoded in the emotional and melancholy “Scenes of the Wu River.”

Lu Hua Bai: “Tibet Suite” (Gunma Symphony Orchestra; Kektjiang Lim, cond.)

Spring in Xinjiang

The remote and rugged region of Tibet has long inspired countless artistic and musical representations. The “Tibet Suite,” by Lu Hua Bai utilizes a full orchestra and prominently features the English horn as a symbol of esoteric Buddhism. Reflecting the cultural heritage of this trans-Himalayan region, a succession of folksongs provides a rustic musical and cultural flavor. Chinese music, not unlike Chinese painting, is typically representational. And such is certainly the case in the energetic “Spring in Xinjiang,” which illustrates the coming of the warm weather in the Northern areas of Chinese Turkestan.

Li Zhong Han/Ma Yao Xian: “Spring in Xinjiang” (Takako Nishizaki, violin; Yit Kin Seow, piano)

The Butterfly Lovers

The legendary story of Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, better known as the “Butterfly Lovers,” has long reverberated in traditional Chinese opera. Localized differences aside—the fundamental narrative appears in Yue, Shaoxing and Sichuan opera—this grievous love story doomed by rigid social conventions is rightfully considered an elemental part of China’s historical heritage. More recently, it has made its way onto the cinematographic screen, and even into the world of serial television and animation. For two students from the Shanghai Conservatory, this folk legend provided the basis for a work for violin and orchestra, aptly named The Butterfly Lovers Concerto. The skillful blending of models and techniques from the Western symphonic tradition with Chinese folk music and local instrumental/vocal techniques created a redolent musical symbolism that has easily become a modern Chinese classic.

Chen Gang/He Zhanhao: The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto (Jie Chen, piano; New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; Carolyn Kuan, cond.)

The musical narrative is divided into three sections, with the solo violin symbolizing Zhu Yingtai and the cello providing the musical portrayal of Liang Shanbo. A single flute enters over an atmospheric accompaniment and presents the introduction for a simple melody sung by the solo violin. This tune originates in the vast repertory devoted to the Yellow River and symbolizes Zhu’s childhood experiences. Tenderly accompanied by harp, flute and strings the mood gradually changes, as Zhu begins her journey to attend school in Hangzhou. An extended solo passage provides the musical connection, as a rhythmically complex and highly animated violin melody anticipates her meeting with Liang. A lush folk tune in the cello, quickly intertwined with ethereal fragments presented in the violin, musically describes their first encounter and the gradual blossoming of friendship and love. That love is violently opposed by her domineering father, and the iconic love duet between the cello and the violin is replaced by Liang’s rage. Zhu’s grief and suicide provoke an emotional outcry, and the flute and harp initiate the process of metamorphosis. The return of the love theme signals the transformation of their souls into butterflies.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter