We recently saw the broadcast on MEZZO of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées’ production of Stravinsky’s Le Rossignol and Poulenc’s Les Mamelles de Tirésias. It’s not a combination one might have imagined, but director Olivier Py has turned the tables on combining the two works. Rossignol is set backstage during a production of Tirésias. On the two-level stage, downstairs central is the bed of the ailing Emperor of China. Upstairs, with dressing tables and lights on each side, is backstage for Tirésias, as we look through to the audience in their boxes.

The Double stage, 2023 (Photo by Vincent Pontet) (Théâtre des Champs-Élysées)

The Stravinsky’s Le Rossignol takes its inspiration from a story by Hans Christian Andersen. The most beautiful songbird in the world is brought to the garden of the Emperor of China and sings for him. All is well until emissaries from Japan bring the emperor a mechanical nightingale. At its ‘song,’ the Emperor is entranced, and the real bird flies away.

Igor Stravinsky: Le rossignol – Act II: Akh! Sérdtse dóbroe (Song of the Nightingale): (Mojca Erdmann, the Nightingale; Vladimir Vaneev, the Emperor; Tuomas Pursio, The Chambellan; Cologne West German Radio Chorus; West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Jukka-Pekka Saraste, cond.)

In the final act, the Emperor is dying and Death has appeared and taken his symbols of power. The Nightingale returns and bargains with Death: she will sing for Death if Death returns the Emperor’s crown, sword, and standard. Death agrees, and the Emperor returns to life. He restores the Nightingale to the position of ‘first singer’ at the court, and the Nightingale, happy to be paid only with the Emperor’s tears, promises to sing for him every night until dawn.

Act II: The Return of the Nightingale, 2023 (Photo by Vincent Pontet) (Théâtre des Champs-Élysées)

Igor Stravinsky: Le rossignol – Act III: Mne slú’ nrávitsya (Mayram Sokolova, Death; Mojca Erdmann, the Nightingale; Vladimir Vaneev, the Emperor; West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Jukka-Pekka Saraste, cond.)

In Théâtre des Champs-Élysées’ production, the Nightingale can only make flying visits because she must be back onstage all the time as the lead in Les Mamelles de Tirésias. There are some genuinely funny moments in this opera of promises and falsehoods: When the courtiers seek the nightingale in the forest, they can’t tell her song from the grunting of pigs or the croaking of frogs until they hear her voice. Japanese ambassadors bring the Emperor not a mechanical bird but a laptop with a large blue ‘Larry the Bird’ symbol of the entity formerly known as Twitter on it.

Twitter’s ‘Larry the Bird’

Le Rossignol was written by Stravinsky in Paris in 1914 and had its premiere in May of that year, just before the war started. Stravinsky was deeply homesick for Russia and sought comfort in the stories from his childhood, many of which have magical feathered creatures. In a similar way, Stravinsky’s The Firebird conjures up another magical bird.

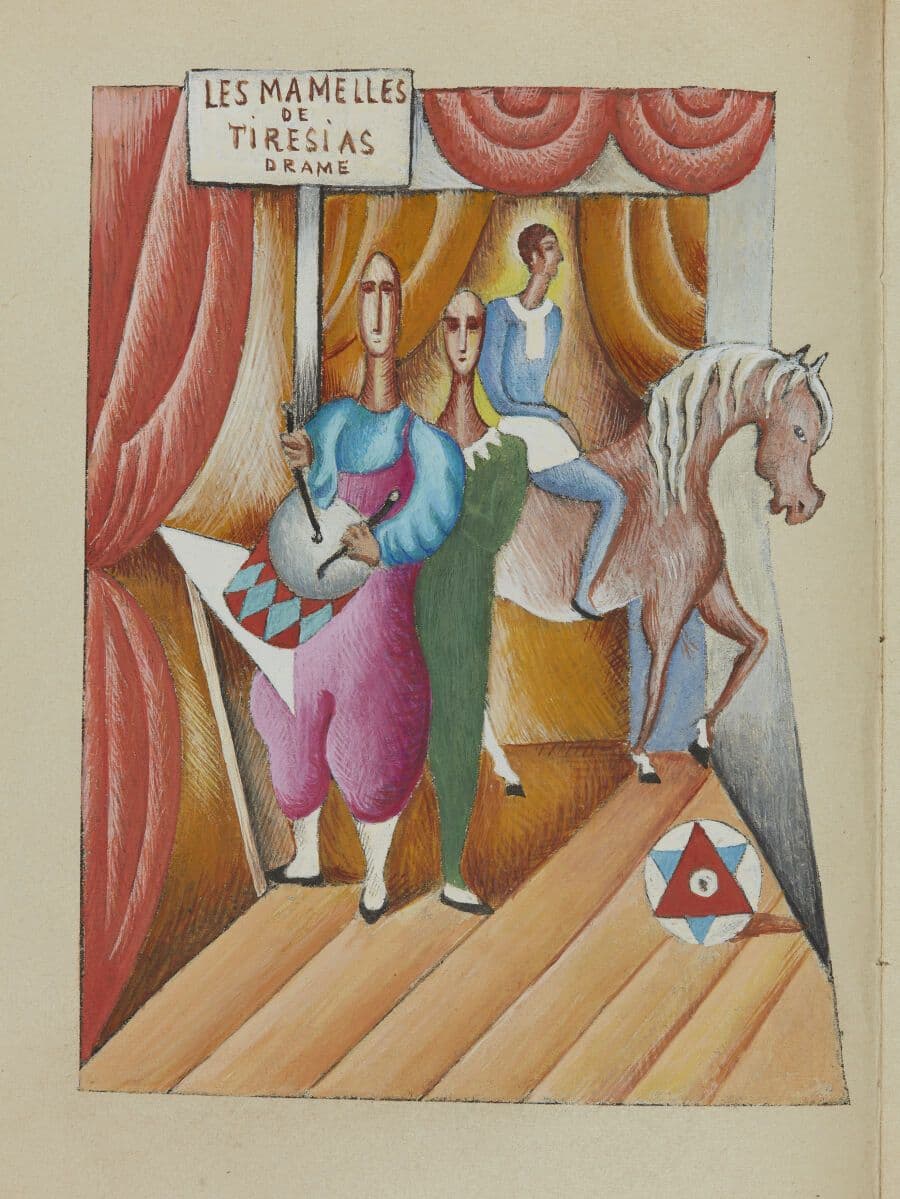

The second opera, Les Mamelles di Tirésias, is one of the few operas that was also intended to be a Public Service Announcement for the government: have more children. Poulenc took his text from Guillaume Apollinaire’s 1903 work of the same name. Apollinare’s play wasn’t given its premiere until 1917 when France was in the midst of WWI; at the time of its premiere, Apollinaire had updated it and added a sombre prologue, bringing the play up to the current time (1917).

Les Mamelles di Tirésias, 1917, design by Serge Férat

Guillaume Apollinaire, 1911

Apollinaire died in 1918 during the Spanish flu epidemic, and when Poulenc requested the use of the text for his opera in 1935, Apollinaire’s widow, Jacqueline Kolb, gave him permission to adapt the play to his needs. One of the adaptations was to change the setting to 1912.

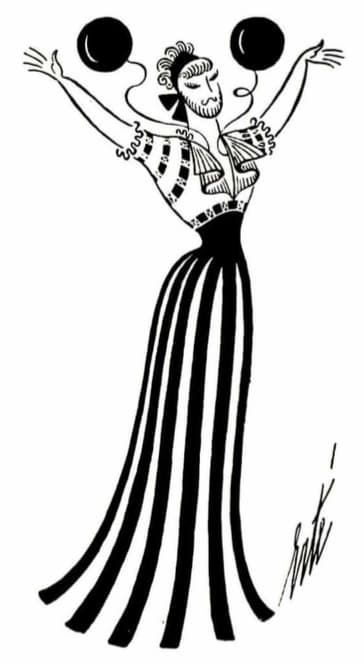

The opera opened on 3 June 1947 with costumes by Erté.

The story is surrealist in the extreme. Thérèse no longer wants to be a submissive wife and turns into the man Tirésias when her breasts float away as balloons. She puts on a beard and dresses like a man and ties up her husband, and dresses him like a woman.

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act I: Non, Monsieur mon mari (Barbara Bonney, Thérèse/Tirésias ; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, the Husband; Tokyo Opera Singers; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Erté: Thérèse turns into Tirésias, 1918

Tirésias turns into General Tirésias and sets off to campaign against childbirth. Her left-behind husband fears this means France will be left childless and sets out to figure out how to bear children without women.

End of Act I: The husband tied in a chair and Tirésias starting her campaign against children, 2023 (Photo by Vincent Pontet) (Théâtre des Champs-Élysées)

Act 2 starts with the husband’s success: He’s had children! Exactly 40, 049 children, to be exact. When a journalist asks how he feeds the horde, the husband ‘explains that the children have all been very successful in careers in the arts and have made him a rich man with their earnings’. A policeman arrives to declare that, because of the overpopulation, the citizens of Zanzibar are now dying of hunger. The husband has ration cards printed up for them by a passing fortune-teller. The gendarme attempts to arrest the fortune-teller but is killed instead. The fortune-teller is revealed as none other than Tirésias returned.

End of Act II: Tirésias’ return as a fortuneteller, babies scattered over the stage, 2023 (Photo by Vincent Pontet) (Théâtre des Champs-Élysées)

The couple reconcile and the whole cast comes to the front of the stage to urge the audience to have children:

Ecoutez, ô Français, les leçons de la guerre

Heed, o Frenchmen, the lessons of the war

Et faites des enfants, vous qui n’en faisiez guère

And make babies, you who hardly ever make them!

Cher public: faites des enfants!

Dear audience: Make babies!

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tiresias, FP 125 – Act II: Il faut s’aimer ou je succombe (Barbara Bonney, Thérèse/Tirésias; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, the Husband; Akemi Sakamoto, A Fat Woman; Wolfgang Holzmair, A Bearded Man; Tokyo Opera Singers; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

By using Erté to design the show and setting it in the style of 30 years earlier, Poulenc was seeking to move it to a more lavish style. The original 1917 setting of Apollinaire was very influenced by Cubism, and by the 1940s, that was considered just too old-fashioned. Yet, by using a style that was older than Cubism, it moves it into the realm of the familiar and yet nostalgic.

Apollinaire: Cover of the publishes play, 1918. Illustration by Serge Férat (Drout.com)

In the same way, the music is old and familiar; it’s very much in a musical hall style – mixing talk and song in a way that would have been familiar to any Parisian devotee of the late 19th century. In this scene, one of the babies, who has become a scandal-seeking journalist, tells him the news of the day, all of it wrong: a general alarm fire destroyed Niagara Falls, the princess of Bergamo is marrying a lady she met in the subway, Picasso is making a picture that moves! (to which his father replies ‘Long live the brush of Picasso!’).

Francis Poulenc: Les mamelles de Tirésias, FP 125 – Act II: Mon cher papa (Anatoly Gridenko, the Son; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, the father; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Poulenc also changed Apollinaire’s original setting of East African Zanzibar to the imaginary town of Zanzibar somewhere on the Mediterranean coast. Director Py’s setting for the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées’ production moves it again, now to the Zanzibar Theatre, presumably in Paris.

This new Paris production is exciting and hits so many current societal questions right on the head. Is social media removing us from the real world? Have we lost our own appreciation for nightingales by staring so intently at the little computers in our hands? Are we losing our intellectual edge by having smaller families while less developed nations are still actively building up their populations? Have we forsaken love for power? We all have our answers to these questions, but it’s rare to see them posed so clearly in an opera production. If you can catch it on MEZZO, it’s an amazing production to see!

The role of the Nightingale and Thérèse / Tirésias is sung by the incomparable Sabine Devieilhe, the role of the Emperor of China and the Husband by Jean-Sébastien Bou with Lucile Richardot as Death in both operas.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter