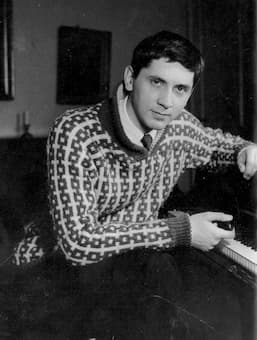

Rautavaara in the 1950s

Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928-2016) was one of the new Finnish composers who followed after Sibelius. He wrote using both 12-tone serial techniques and in a neo-romantic style. He started his music education with his father, an opera singer and cantor, but his father’s early death (when Rautavaara was 10 years old) and his mother’s death 6 years later left the teenager in the hands of his aunt in Turku. He started piano lessons at age 17 before he went to study piano at the University of Helsinki and composition at the Sibelius Academy. His success at composition led Jean Sibelius to recommend for a scholarship to The Juilliard School. There, he studies with Vincent Persichetti, with summer study at Tanglewood with Roger Sessions and Aaron Copland.

This time in America in the 1950s was an important period for him as a composer – living in Manhattan was as much an education as his time in the classroom.

In his work Lost Landscapes, completed shortly before his death, Rautavaara made Tanglewood the first movement. The landscapes functioned as ‘musical life themes’ for Rautavaara, causing him to think over his life and bring it back to life in his vivid recollections. The first movement covers his summer courses at Tanglewood in 1955 and 1956, culminating in an intensive Romantic build up to a softer ending. The work’s lush landscape shows us the setting for our young composer.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Lost Landscapes (version for violin and orchestra) – I. Tanglewood (Simone Lamsma, violin; Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Robert Trevino, cond.)

Rautavaara returned to Finland and completed his work at the Sibelius Academy in 1957. Later that same year, he went to Ascona, Switzerland to study with Swiss composer Wladimir Vogel. This is where he first learned 12-tone technique and the style of the music changes to searching and restless. The tempos shift and the lush Romanticism of the first movement is gone.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Lost Landscapes (version for violin and orchestra) – II. Ascona (Simone Lamsma, violin; Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Robert Trevino, cond.)

Palais Schönberg

The third movement, Rainergasse 11, Vienna, is the address of an early 18th-century Baroque building where Rautavaara lived in spring 1955. The Palais Schönberg was renovated in 2008 and can now be rented for events such as weddings and parties. After the war, however, it was still the home of the impoverished princely family who rented out rooms to foreign music students. The house had suffered bomb damaged during the war, but had been restored in the mid-1950s.

The music is melancholic, reflecting this building as a monument to a lost era and a lost culture. The music, like the building, is caught out of time.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Lost Landscapes (version for violin and orchestra) – III. Rainergasse 11, Vienna (Simone Lamsma, violin; Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Robert Trevino, cond.)

Rautavaara in 2014 (Photo by Teemu Rajala)

Rautavaara’s last landscape returns him to New York, during the winter of 1955-56. He would have been at Tanglewood for the summers before and after this time, but now he’s back in the bustle and busyness of the city. West 23rd Street is the heart of Chelsea, one of New York’s art neighborhoods. In the late 19th century, this was ‘midtown,’ where the well-to-do did their shopping, with most of the major department stores here. In the early 20th century, midtown moved further up sixth Avenue, and the area was left with big buildings that became warehouses and lofts. As a core of Manhattan, 23rd Street remains a vibrant heart of the city and Rautavaara captured this in the movement.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: Lost Landscapes (version for violin and orchestra) – IV. West 23rd Street, NY (Simone Lamsma, violin; Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Robert Trevino, cond.)

A young composer develops his style under the guidance of his mentors. It’s rare for a composer to look back at that time of learning in such a comprehensive way – we can hear each new experience of Rautavaara, from the excitement of New York to the ruined history of Vienna and from the Romantic holdovers of the last century to the new explorations he was making under his teachers, from Persichetti to Vogel. It’s a lovely view from the top of the hill at the places that lead him to where he was 60 years later in his life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter