Hedy Lamarr

Do you know the joke about the Hollywood screen goddess and the bad boy of music collaborating to invent a remote-controlled torpedo? Funny enough, it actually isn’t a joke but a delightful anecdote from the pages of music and science history. The actress in question was Hedy Lamarr, called by the MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer, “the most beautiful girl in the world.” Hedy was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna in 1913, but escaping a tyrannical husband and Europe’s growing anti-Semitism, she arrived in Hollywood in 1937. By 1938 she had established her star potential with a stunning performance in Algiers, and in her extended acting career she starred in over 30 films. Irritated at always being typecast as the glamorous beauty, she co-founded a new production studio and starred in its films. As she once famously said, “Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” The bad boy of music was no other than the dashing American George Antheil (1900-1959). A child prodigy, he dropped out of school and left for Europe. In no time at all he rubbed shoulders with Ezra Pound and James Joyce, made friends with Gertrude Stein and Leopold Stokowski, and was looking to upstage Igor Stravinsky.

George Antheil: A Jazz Symphony (1925 version) (Frank Dupree, piano; Adrian Brendle, piano; Uram Kim, piano; Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Karl-Heinz Steffens, cond.)

George Antheil

Antheil was the first American to write an opera premiered at a major European house; he wrote movie music, a lonely-hearts column for a Los Angeles daily, and a book or two on glandular criminology. And let’s not forget his 1945 autobiography Bad Body of Music. In his music, he used the percussive rhythmic devices of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring not as an evocation of the primitive but to convey the mindless energy of machines. Antheil didn’t go to Paris to blend in, he went there to outrage, shock, and offend. He quickly learned to manipulate the press, as scandal was the international passport to fame. He supposedly kept a loaded revolver on the piano while playing recitals in order to discourage audience protest. His groundbreaking Ballet Mécanique of 1924 caused an uproar at its Paris premiere. It was written to include the synchronization of 16 player pianos, and the composer gave the following performing instruction. “Scored for countless numbers of player pianos. All percussive. Like machines. All efficiency. NO LOVE. Written without sympathy. Written cold as an army operates.”

George Antheil: Ballet Mécanique (Philadelphia Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra; Daniel Spalding, cond.)

Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil

Antheil and his wife Boski lived in Paris for more than 10 years, and they subsequently moved to Hollywood shortly before Hedy Lamarr’s arrival. George met Hedy at a Hollywood dinner party, and he later admitted that his “eyeballs sizzled, and that her breasts were fine too.” They probably did not have an affair because Hedy preferred tall men, and Antheil was described by Time magazine as “cello-sized.” Antheil did claim that Lamarr wrote her telephone number in lipstick on the windshield of his car that first night. Be that as it may, at some point they had a conversation about Hedy’s ex-husband in Vienna. His name was Friedrich Mandl, a Viennese arms merchant and munitions manufacturer reputed to be the third-richest man in Austria. She was 18 and he was 33, and her parents did not approve of Mandl as he had ties to Benito Mussolini, and later Adolf Hitler. Mandl prevented Hedy from pursuing an acting career, and she claimed that she “was kept a virtual prisoner in their castle home.” She did, however, accompany her husband on business trips, and they attended various scientific conferences on military technology. These conferences served as her introduction to the field of applied sciences. Once she had fled her husband and landed in America, she began to think about how she could help the war effort in the United States.

George Antheil: “Jazz Sonata,” Piano Sonata No. 4 (Marthanne Verbit, piano)

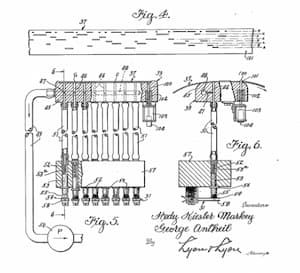

The joint patent for the torpedo with a radio-guidance system

Lamarr was seriously bored with her acting career, so she started to “invent challenge to amuse herself, and to bring order to a world she thought chaotic.” Apparently, Howard Hughes once provided her with a pair of chemists to assist with one of her ideas of inventing a bouillon cube that would create a cola-like soft dink when dropped into water. But what really intrigued her was the problem that radio-controlled torpedoes were easily jammed and set of course. Together with George Antheil, who was the expert in making machines communicate with one another, she came up with the idea of using an encrypted frequency-hopping signal to avoid the jamming. The device was based on the idea of a piano roll that randomly changed the signal sent between the control center and torpedo at short bursts within a range of 88 frequencies on the spectrum, corresponding to the 88 black and white keys on a piano keyboard. Lamarr and Antheil ultimately obtained a joint patent in 1942 for this torpedo with a radio-guidance system. The military never picked up the idea, but her achievements were finally recognized in 1997 when she received a “Pioneer Award” from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In fact, “her idea was a precursor to spread-spectrum technology—or digital wireless communications—that gives us wireless phones, GPS and Wi-fi today. Antheil died in 1959 and was quickly forgotten, and Lamarr got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Posthumously, both were inducted in 2014 in the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Antheil: 4-hand Suite (Guy Livingston, piano; Philippe Keler, piano)