Brahms

Fest und Gedenkspruche, Op. 109

Strauss II

Schoenberg

Verklarte Nacht (Transfigured Night), Op. 4 (version for string orchestra)

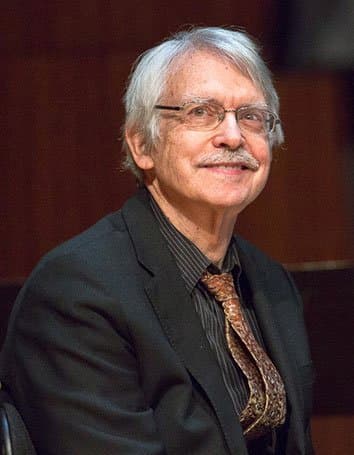

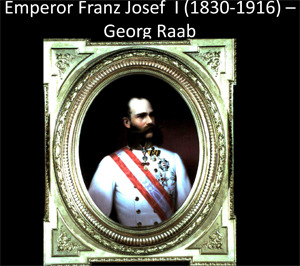

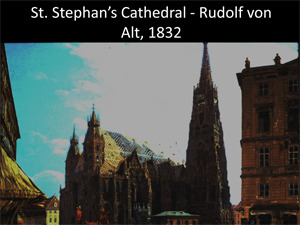

Emperor Franz Josef I came to power after the revolution of 1848 – a time which saw the ascendancy of the liberal middle class. In 1860 their increasing power manifested itself with their hold over the city of Vienna. Until that time, Vienna, in comparison to other European capitals, had been rather backward, with the center of the old city (the Hofburg/Winter Palace, St. Stephan’s Cathedral, the Baroque palaces of the aristocracy, etc.) still surrounded by defensive walls. As a result of the revolutions earlier in the 19th century, the Habsburgs realized that its enemies were no longer foreign attackers (i.e., the ‘hated’ Turks, who had threatened the city in 1683 for the last time), but its own citizenry.

In 1857, Emperor Franz Josef issued a decree that the city walls and the surrounding ‘glacis’ be transformed for the development of the ‘Ringstrasse’ (Ringstreet). The Ringstrasse in Vienna, like the ‘Grand Boulevards’ in Paris, which were planned by Baron Haussmann under Napoléon III, would now allow free movement of troops to defend the city center. In Vienna however, it would at the same time isolate the center physically and psychologically from the city’s growing suburbs.

Many well-known architects were commissioned to develop the entire Ringstrasse area and the chosen architectural style was historicism, i.e., buildings which reflected the diverse architectural styles of the past centuries. The liberal class wanted Vienna’s Ringstrasse buildings, ‘Prachtbauten’ (magnificent buildings) as they called them, to reflect its growing power, to project its ideals and values – rational, scientific and orderly. Whereas the architecture of the old city center, particularly that of the Baroque period, reflected the unity and relationship of each of the buildings in reference to their surroundings, the Ringstrasse buildings were just aligned in reference to the Ring itself and projected an image of a ‘mythical’ past, which the liberal class found representative of its own standing.

The Neo-Gothic Town Hall was to represent the ‘democratic’ role of ordinary ‘town councilmen’ during the Middle Ages; the Neo-Renaissance style of the Fine Arts Museum was to reflect the importance and re-birth of the classical arts during Renaissance times; the Neo Baroque style of the State Opera emphasized the importance of opera during the Baroque era when ‘ordinary citizens’ could join the aristocracy in a shared experience; the Neo-Classical style of Vienna’s Parliament was to evoke the Greek ideal of democracy, with the statue of Pallas Athena prominently displayed in front of it – although at a time in which only the aristocracy and wealthy landowners were allowed to vote and most of the lower classes were disenfranchised.

The palaces of the aristocracy and ‘regular’ apartment buildings along the Ring were also built at that time. In the latter, the vertical stratification of the different classes became visible – the street level contained shops, the ‘piano nobile’ for wealthy citizens, i.e., first and second floor apartments were highly decorated and could be reached by a main staircase, whereas the upper floors, the smaller and less ornamented apartments of the bourgeoisie, could only be reached by a separate ‘back stairs’ staircase.

Criticism, particularly from the young contemporary architects such as Otto Wagner, Camillo Sitte, Adolf Loos, Josef Maria Olbrich and others, was fierce. Adolf Loos called the Ring buildings “Potemkinstrasse”. He and the others rejected the meaningless styles of the past and the fact that the buildings were just aligned on the Ring without any reference to their surroundings. In fact, it was the younger generation of artists, architects, painters, writers and musicians, who would reject ‘historicism’ in all of its forms, and would demand that all of their artistic creations should reflect their time – embodied in the inscription of Olbrich’s Secession building: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst – der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To each Time its Art – to Art its Freedom).

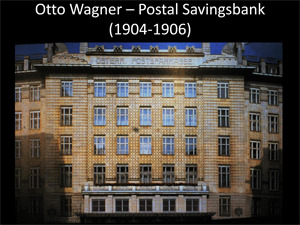

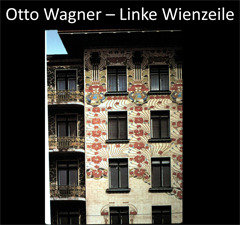

Otto Wagner’s buildings, the Postal Savings Bank, the Metro Stop, the Linke Wienzeile buildings would now emphasize the construction of the buildings themselves, making visible their supporting beams and their new glass and reinforced concrete materials. There was a new interest in stylized decorations, and in the influence of other cultures such as those of the Far East and Byzantium. This, of course, reflects the very ideas which I had discussed regarding the art of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting and music (see my earlier article in Interlude), where structure and technique had also become visible.

In 1812 Vienna saw the establishment of the ‘Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde’ (The Society of Friends of Music). The famous building, the Musikverein (where all of the New Year’s concerts are broadcast from its acoustically perfect Golden Hall), was itself also built as part of the development of the Ringstrasse project in the latter part of the century. Here, the composers of the First Generation, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and increasingly Schubert were heard, but new voices started to appear and would promote the music of the composers of the second half of the 19thcentury, Wagner, Bruckner, Brahms and Mahler. Whereas the Habsburg court danced to the waltzes of Johann Strauss, father and son, the general public listened to their music in the Stadtpark (City Park) and saw their popular operettas, such as ‘Die Fledermaus, Der Zigeunerbaron, Die Lustige Witwe’ (The Bat, The Gypsy Baron, The Merry Widow) in the Volkstheater (People’s Theater).

Gustav Mahler had great influence as the opera conductor in Vienna and elsewhere, and insisted on the highest standards in staging and performance. He introduced works of the Romantic composers Carl Maria von Weber, Hector Berlioz, and later, Richard Wagner to the Viennese public. Wagner’s conception of opera as ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (The work of art considered as totality) would influence musicians and artists in the following years, including Gustav Klimt’s generation of painters, the artists of the ‘Wiener Werkstätte’ (Viennese Workshops), and the composers Vienna’s Second Generation, Schoenberg, Berg and Webern.