Basilica di Santa Maria

del Fiore

Guillaume Dufay, Nuper rosarum flores

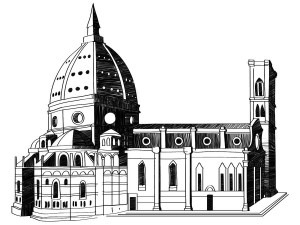

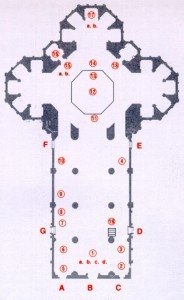

For almost 600 years, the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) has dominated the cityscape of Florence. Build on the site of an earlier cathedral dedicated to Saint Reparata — a third century Christian virgin and martyr — construction of the new “Duomo” officially began in 1296 and lasted for the better part of 140 years. Based on designs by Arnolfo DI Cambio, who concurrently oversaw the construction of the church of Santa Croce and the Palazzo Vecchio — the impressive fortress-palace guarded by Michelangelo’s David that served as the town hall of Florence — the floor plan of the new cathedral adhered to the form of a Latin cross. A central nave of four square-bays is framed by aisle on either side, with the chancel and transepts sporting identical polygonal designs, which in turn are separated by two polygonal chapels.

Although this kind of design was relatively common, the dimensions of the new cathedral were simply astounding. 153 meters long and 90 meters wide at the crossing, it reaches a dizzying height of 90 meters from the pavement to the opening of the lantern. Once completed, it was the largest European church of its time. After nearly one hundred years of construction, the cathedral was still missing its most iconic feature, the enormous octagonal dome. Cambio’s design called for a structure wider and higher than anything previously attempted, and most significantly, it rejected external buttresses. To accomplish this novel architectural feat, the city hired Filippo Brunelleschi, one of the foremost architects and engineers of the Italian Renaissance. The planning and construction process posed a large number of technical problems, among them how to prevent the dome from collapsing under its own weight during the building process. Since the dome started 52 meters above the floor and spanned 44 meters, there was simply “not enough timber in Tuscany to build the scaffolding and forms.”

Although this kind of design was relatively common, the dimensions of the new cathedral were simply astounding. 153 meters long and 90 meters wide at the crossing, it reaches a dizzying height of 90 meters from the pavement to the opening of the lantern. Once completed, it was the largest European church of its time. After nearly one hundred years of construction, the cathedral was still missing its most iconic feature, the enormous octagonal dome. Cambio’s design called for a structure wider and higher than anything previously attempted, and most significantly, it rejected external buttresses. To accomplish this novel architectural feat, the city hired Filippo Brunelleschi, one of the foremost architects and engineers of the Italian Renaissance. The planning and construction process posed a large number of technical problems, among them how to prevent the dome from collapsing under its own weight during the building process. Since the dome started 52 meters above the floor and spanned 44 meters, there was simply “not enough timber in Tuscany to build the scaffolding and forms.”

Brunelleschi’s solution called for the employment of a double shell, made of sandstone and marble, with the inner shell held together by four internal and horizontal stone and iron chains, in the manner of a barrel hoop. Each course of bricks thus becomes a horizontal arch that resists compression. The outer dome, on the other hand, is a brick shell, merely 60 centimeters thick at the base and 30 centimeters thick at the top. In all, Brunelleschi’s used more than 4 million bricks in the construction of the dome, and invented hoisting machinery to lift the masonry into position. To top it all, a conical lantern sporting a copper ball and cross crowned the dome. The sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio designed the copper ball, and his young apprentice Leonardo da Vinci made a series of sketches of the hoisting machines. The total height of the dome and lantern reaches an astonishing 114.5 meters. The cathedral is framed by the Baptistery of St. John—an octagonal structure built between 1059 and 1128, which saw the baptism of Dante Alighieri and various members of the Medici family — and the freestanding campanile designed by Giotto and completed in 1359.

Brunelleschi’s solution called for the employment of a double shell, made of sandstone and marble, with the inner shell held together by four internal and horizontal stone and iron chains, in the manner of a barrel hoop. Each course of bricks thus becomes a horizontal arch that resists compression. The outer dome, on the other hand, is a brick shell, merely 60 centimeters thick at the base and 30 centimeters thick at the top. In all, Brunelleschi’s used more than 4 million bricks in the construction of the dome, and invented hoisting machinery to lift the masonry into position. To top it all, a conical lantern sporting a copper ball and cross crowned the dome. The sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio designed the copper ball, and his young apprentice Leonardo da Vinci made a series of sketches of the hoisting machines. The total height of the dome and lantern reaches an astonishing 114.5 meters. The cathedral is framed by the Baptistery of St. John—an octagonal structure built between 1059 and 1128, which saw the baptism of Dante Alighieri and various members of the Medici family — and the freestanding campanile designed by Giotto and completed in 1359.

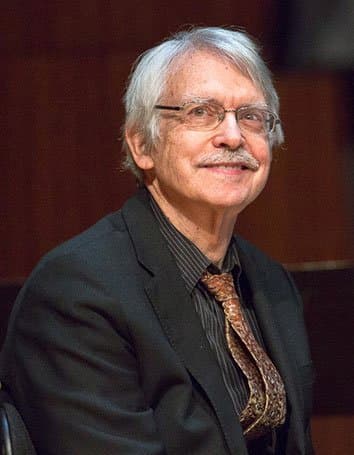

Guillaume Dufay

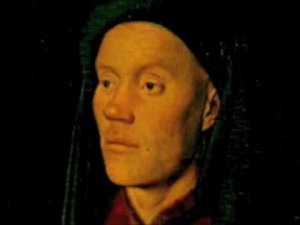

After nearly 140 years of construction and interior decoration, Pope Eugenius IV consecrated the cathedral on 25 March 1436. For this special occasion, the Franco-Flemish composer Guillaume Dufay — one of the most famous and influential composers of his time, and serving as a member of the Papal Chapel — composed his motet Nuper Rosarum Flores, ex dono pontificis (Recently garlands of roses were given by the Pope). The title of the composition derives from the name of the cathedral itself, and the opening lines describe the golden rose Pope Eugene IV presented as a gift to the cathedral. Borrowing a melody from Gregorian chant, Dufay composes a musical structure that relies on a pair of interlocking tenor parts.

Floorplan of the Basilica

Stated four times under different mensuration signs — which essentially presents the tenor melody at different speeds — the overall length proportions of the motet adheres to a ration of 6:4:2:3. According to Charles Warren, “this proportional structure mimicked the essential proportions of the cathedral itself,” as it imitated the architecture of the façade. More recently, however, Craig Wright has suggested that the inspiration for Dufay’s motet was not architecture, “but a biblical passage providing the supposed dimension of the Temple of Solomon as 60x40x20x30 cubits.” Whatever the case might actually have been, there can be no doubt that the performance in 1436 achieved an electrifying synergy between architectural and musical space.