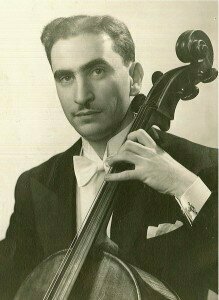

Janet’s father, George Horvath

But my étude-playing impressed an advanced teacher who later admitted that he didn’t think anyone as diminutive as I, with tiny hands, would ever be able to play the cello.

Today the above-mentioned cellists are known primarily by countless cello students who have grappled with their études (or avoided them). But these artists set extremely high standards of playing, and taught some of the greatest soloists, including Piatigorsky, Feuermann, Suggia, Mainardi, and Beatrice Harrison, among others.

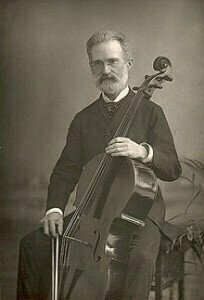

Friedrich Dotzauer

Dotzauer: Etude in D Major, Op. 158, No. 2: Presto

Although he still played without an end-pin, Dotzauer was the first cellist to advocate holding the bow close to the frog in a relaxed manner as we do today, and to play with a free and natural bow-arm. Due to his influence, Dresden became recognized as a center for the highest caliber of cello playing. As a prolific composer, who wrote an astounding number of symphonies, operas, sonatas, chamber music, and innumerable cello works, which have practically vanished, he is well-known for his Three Violoncello Schools of 113 études, exercises, and caprices for unaccompanied cello.

Piatti: Caprice No. 7

Alfred Piatti

Janos Starker – Piatti: Caprice No. 9

Piatti had a long and distinguished teaching career. The German cellists Robert Haussmann, (who premiered the Brahms Double Concerto and for whom Bruch wrote his Kol Nidrei) and Hugo Becker, William Whitehouse and many others, studied with him.

Audiences of the day had come to expect salon and virtuoso pieces in concerts. Piatti tried to enhance the cello repertoire with artistic and serious works and was the first to publish 18th century sonatas that were forgotten in dusty libraries—works by Locatelli, Porpora, Valentini, Veracini, Ariosti, Marcello, and Boccherini. Cello teachers of today still recommend Piatti’s Caprices.

Friedrich Grüzmacher

After he moved to Leipzig in 1848, he was heard by the famous violinist Ferdinand David who arranged a concert for Grüzmacher—invaluable exposure for the cellist. When Cossmann left Leipzig, Grüzmacher became the principal cello of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, professor at the Leipzig Conservatory, and performed in the David String Quartet. Several years later he took the position of principal of another esteemed orchestra—the Court Orchestra of Dresden, and became the cellist of the Kammervirtuos to the King of Saxony. He toured Europe and Russia and was known for his technical mastery and tantalizing musicality.

Grüzmacher composed and arranged a huge number of methods and pieces, like Piatti, to bolster the cello repertoire. He was one of the first to include sonatas on his programs, by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin and Grieg.

Janos Starker – Grützmacher: Etude No. 21 in D Major

A formidable teacher, Hugo Becker was one of his many accomplished students. Grüzmacher is known more for his études than his arrangements and transcriptions. He certainly used “poetic license.” His edition of the famous Boccherini Concerto in B flat, still used today, is a compilation of four different works. According to Margaret Campbell in The Great Cellists, “although both Anner Bylsma and Maurice Gendron have researched into the originals and have dared to redress the balance…many modern players are unaware of the inaccuracies in the edited version.” At least Grüzmacher made the public aware of the music of Boccherini! Grüzmacher’s cadenzas for the concerto and the Haydn D Major Concerto are still performed today as are his darned difficult studies.

Fortunately, many of the studies are graduated and are playable for beginners. Are you practicing your études? I am. They are sometimes required repertoire for competitions and auditions.

Duport: Etude No. 7

Steuart Pincombe performed on an original, rare 1727 Carlo Antonio Testore