Paul Klee (1879-1940) craved the freedom to explore radical and modernist experimentations in his paintings. In music, however, he could never come to terms with contemporary works of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. In fact, he even disliked the compositions of Wagner, Bruckner and Mahler. Klee was a gifted musician who studied voice, piano, organ and violin at the Stuttgart Conservatory. At age 11, he became a member of the violin section of the Bern Music Association, and was on track for a professional musical career. Yet during his teenage years, Klee decided to focus on the visual arts because he found “the idea of going in for music creatively not particularly attractive in view of the decline in the history of musical achievement.” For Klee, modern music lacked meaning, and he believed that the ultimate greatness of Bach and Mozart could never be reproduced in the musical medium.

Paul Klee (1879-1940) craved the freedom to explore radical and modernist experimentations in his paintings. In music, however, he could never come to terms with contemporary works of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. In fact, he even disliked the compositions of Wagner, Bruckner and Mahler. Klee was a gifted musician who studied voice, piano, organ and violin at the Stuttgart Conservatory. At age 11, he became a member of the violin section of the Bern Music Association, and was on track for a professional musical career. Yet during his teenage years, Klee decided to focus on the visual arts because he found “the idea of going in for music creatively not particularly attractive in view of the decline in the history of musical achievement.” For Klee, modern music lacked meaning, and he believed that the ultimate greatness of Bach and Mozart could never be reproduced in the musical medium.

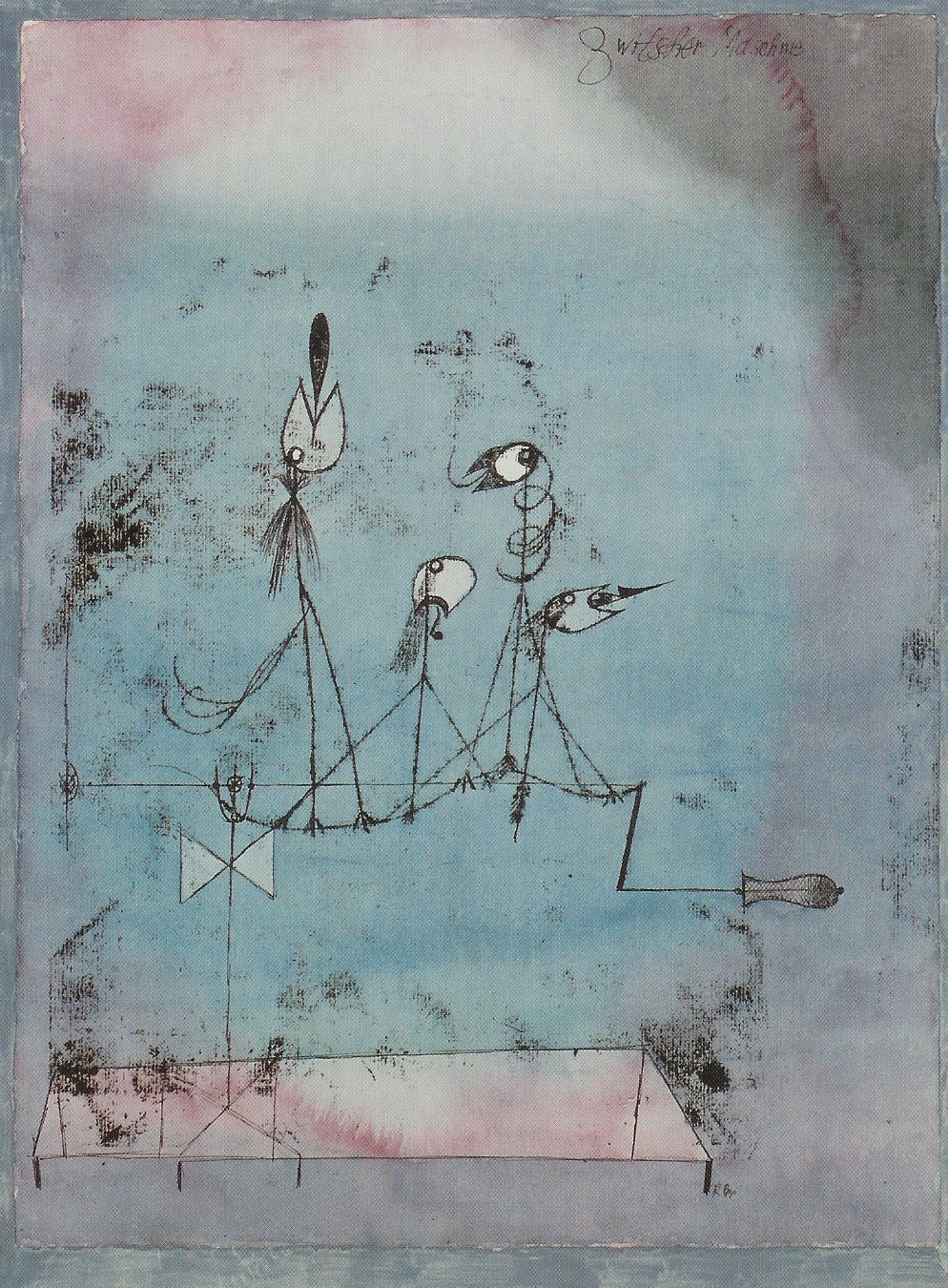

For Klee, the music of Bach and Mozart was the essential key to the mysteries of creation. Both composers, according to Klee, aspired to the notion of universality. Their musical compositions hold appeal for everyone, the connoisseur, the professional and the amateur. Since music in the 20th century had lost this sense of universality, Klee envisioned an art of the future, which translated the musical accomplishments of Bach and Mozart into visual terms. Klee became intensely preoccupied with the parallels between music and painting, and in his opinion “rhythm was an important link between the two genres, capable of illustrating temporal movements in both.” Theoretically, the philosopher and social critic Theodore Adorno had described these points of convergence between music and painting, but practically, it was Paul Klee’s work that visually revealed the points of contact between two different art forms.

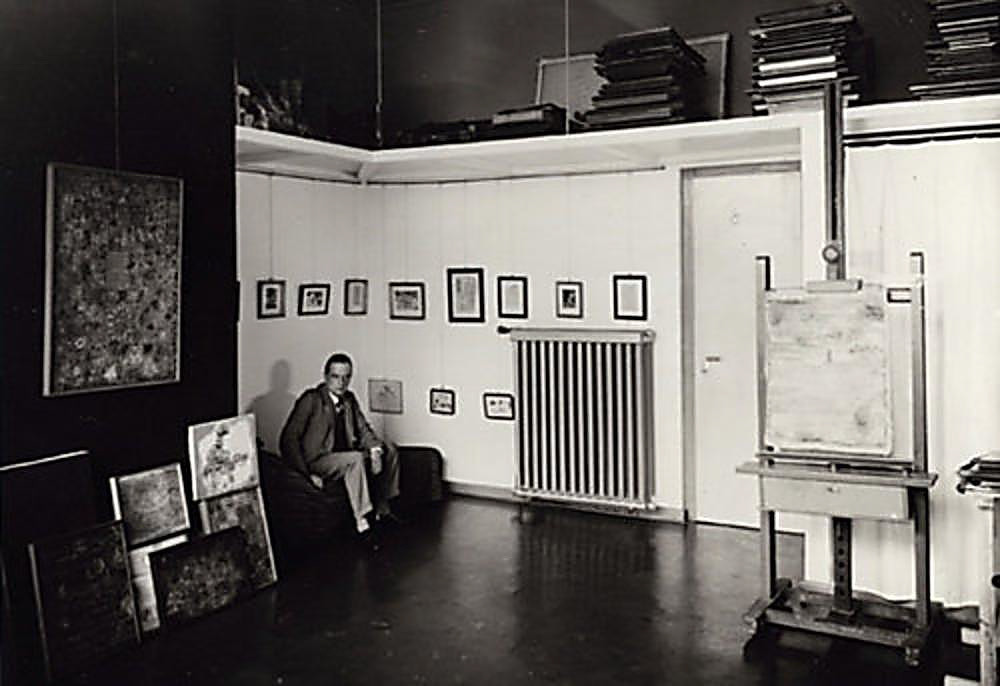

Credit: http://bauhaus-online.de/

For the novelist Wilhelm Hausenstein, “Klee’s attitude is immediately understandable for musical people. Klee is one of the most delightsome violinists, playing Bach and Mozart, who ever walked on earth. For Klee, the musical world became his companion, possibly even a part of his art.” Given the ease with which Klee moved between artistic worlds, it is hardly surprising that a number of composers have musically encoded his paintings as well. Among them, Peter Maxwell Davies, Harrison Birtwistle, Edison Denisov and Tōru Takemitsu, to name only a selected few. On occasion, you can still hear Gunther Schuller’s Seven Studies on Klee Pictures performed on stage. Composed in 1959, the work is located halfway between jazz and classical music. “Each of the seven pieces bears a slightly different relationship to the original Klee picture from which it stems,” Schuller wrote. “Some relate to the actual design, shape, or color scheme of the painting, while others take the general mode of the picture or its title as a point of departure.” The music of Bach and Mozart has inspired some of the most progressive art of our time, and artists like Paul Klee devoted their lives to translate this universal music into the language of visual art.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Fugue in G minor, K. 401