Imagine a world without language — a world where sounds were merely frequencies on a spectrum, and where the rules of writing and speech did not exist. It would be virtually impossible to imagine how human civilization would have developed, how history would have unfolded, or how science and technology would have progressed as we know it today.

Imagine a world without language — a world where sounds were merely frequencies on a spectrum, and where the rules of writing and speech did not exist. It would be virtually impossible to imagine how human civilization would have developed, how history would have unfolded, or how science and technology would have progressed as we know it today.

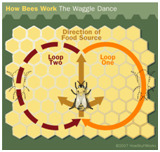

Language is entirely unique to the human species, because it is learnt after birth rather than innate. In contrast, other social animals like bees, birds or apes often communicate with an innate and possibly genetic set of signals, which explains why all known species of honey bees around the world ‘dance’ in a similar fashion to communicate the location of food sources.

Human language, on the other hand, is a complex system that is constantly developing through the input and creativity of its users, who arbitrarily assign meaning to different sounds. This explains why languages are culture-specific rather than universal, with up to 6000 different living languages currently used in various regions across the world. It is found that the section of the brain that organizes sound and meaning to process language is unique to humans.

Music’s Existence Before Language

Music on the other hand, is speculated to have existed long before language. The earliest signs of music were found in Slovenia and France in the form of 53,000 year-old flutes made by Neanderthals out of animal bones. In human development, babies cannot speak without first learning language through communication, yet they appear to have inborn musical preferences, and respond to music while still in the womb. Vaneechoutte & Skolyes (1998) claim we can speak because our species first could sing, and therefore children still use melody as one of the most important clues to acquire spoken language. “All humans come into the world with an innate capability for music,” agrees Kay Shelemay, professor of music at Harvard. This inborn capability to process music may explain why no culture on earth has been found to be absent of music.

Music on the other hand, is speculated to have existed long before language. The earliest signs of music were found in Slovenia and France in the form of 53,000 year-old flutes made by Neanderthals out of animal bones. In human development, babies cannot speak without first learning language through communication, yet they appear to have inborn musical preferences, and respond to music while still in the womb. Vaneechoutte & Skolyes (1998) claim we can speak because our species first could sing, and therefore children still use melody as one of the most important clues to acquire spoken language. “All humans come into the world with an innate capability for music,” agrees Kay Shelemay, professor of music at Harvard. This inborn capability to process music may explain why no culture on earth has been found to be absent of music.

The Relationship between Music and Language

While many debate that music is clearly distinct from language, researchers at Georgetown Universal Medical Center have found evidence that music and language do indeed depend on some of the same brain systems based in the temporal lobes. This may be because both language and music share a lot in terms of their rich rhythmic and melodic structure, and their association with emotions. It is no wonder that musicians have shown to have a more developed left planum temporales and greater word memory. Music was what helped Thomas Jefferson complete the Declaration of Independence. He was said to play his violin when he could not figure out the wordings for a certain part, and doing so helped him articulate his thoughts into writing.

It has also been theorized that an individual’s musical ability is greatly influenced by the tones present in one’s native language. For instance, a study in 2004 found that native speakers of tonal languages such as Mandarin Chinese were found to be almost 9 times more likely to have perfect pitch than students of non-tonal languages, such as English. Likewise, it has been found that children with dyslexia, who find it difficult to count the number of syllables in spoken words, are found to have difficulties in perceiving rhythmic patterns in music.

Historically-speaking, language has had a tremendous impact on the development of music. In Republic, Plato’s philosophy insisted that the rhythm of music must follow that of speech, and not the other way around. This was because he believed the power of music comes from arousing emotions via imitation of human speech. Greek theatre and music also emphasized the perfect union of words and melody, and that music should be sung with the correct and natural declamation as they would be spoken.

Historically-speaking, language has had a tremendous impact on the development of music. In Republic, Plato’s philosophy insisted that the rhythm of music must follow that of speech, and not the other way around. This was because he believed the power of music comes from arousing emotions via imitation of human speech. Greek theatre and music also emphasized the perfect union of words and melody, and that music should be sung with the correct and natural declamation as they would be spoken.

In the second half of the 16th century, the development of complicated polyphonic music in the church was criticized for compromising the intelligibility of words. A simplified version of polyphonic music was hence introduced, with the setting of text kept more faithful to the rhythm and pace of speech. Likewise, with the invention of opera in the same period, monody was introduced as a form of accompanied musical declamation — a style of music based on the tone of emotional speech.

The Power of Music on Memory and Learning

Although research concerning the relationship between music, language and the brain is still in its early stages, the power of music to affect memory and learning is undisputed.

The study of Mozart’s music and baroque music, with a 60 beats per minute beat pattern, has been shown to activate both the left and right brain to maximize learning and retention of information. Even animals exposed to Mozart (compared to other or no auditory stimulation) have shown to complete spatial mazes faster and more accurately. Albert Einstein was once labeled by teachers as “too stupid to learn”, but today he is recognized as the most intelligent person to have ever lived. His friend G.J. Withrow said that Einstein figured out his problems and equations by improvising on the violin. These observations have led to the theory that music and spatial temporal reasoning may activate the same neural pathways in the hippocampus of the brain.

The study of Mozart’s music and baroque music, with a 60 beats per minute beat pattern, has been shown to activate both the left and right brain to maximize learning and retention of information. Even animals exposed to Mozart (compared to other or no auditory stimulation) have shown to complete spatial mazes faster and more accurately. Albert Einstein was once labeled by teachers as “too stupid to learn”, but today he is recognized as the most intelligent person to have ever lived. His friend G.J. Withrow said that Einstein figured out his problems and equations by improvising on the violin. These observations have led to the theory that music and spatial temporal reasoning may activate the same neural pathways in the hippocampus of the brain.

The importance of both language and music as the vehicle for thought, knowledge, and expression, is just one of the many things we take for granted. When and how the special talent of music and language emerged is impossible to say, but it is generally assumed they have originated when early hominids started cooperating, along with an increase in brain capacity.

Because so little is truly known about how the brain works, and because music recording was not available until the 19th century, it is difficult to make any final conclusions about the truth behind music and language. What we do know, is that both have become so deeply entrenched in human culture, that apart from being used to communicate and share information, they also share important social and cultural functions, such as signifying group identity, sentiment and entertainment. It is no wonder that Music is said to be the universal language that can transcend boundaries and bond people even thousands of miles apart.

References:

Cromie, W. J. (2002). Music on the Brain: researchers explore the biology of music. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Harvard University Gazette: http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/2001/03.22/04-music.html

Downey, G. (2010, July 21). Life without Language. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Neuroanthropology: For a greater understaind of the encultured brain and body: http://neuroanthropology.net/2010/07/21/life-without-language

Elsevier (2011, June 29). Dyslexia linked to difficulties in perceiving rhythmic patterns in music. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from http://www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2011/06/110629083113.htm

Gascoigne, B. (2001). History of Language. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from History World: http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab13

Hadley, D. (2011). Honey Bees–Communication Within the Honey Bee Colony. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from About.com Insects: http://insects.about.com/od/antsbeeswasps/p/honeybeecommun.htm

Imagine a world without language. (2010, March 10). Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Tech-FAQ: http://www.tech-faq.com/imagine-a-world-without-language.html

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (2011, February 18). Crossing borders in language science: What bilinguals tell us about mind and brain. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from http://www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2011/02/110218092531.htm

Munger, D. (2008, June 19 ). Does Music help us learn language? Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Cognitive Daily: A new cognitive psychlogy article nearly every day: http://scienceblogs.com/cognitivedaily/2008/06/does_music_help_us_learn_langu.php

Music And Language Are Processed By The Same Brain Systems. (2007, Sep 28). Retrieved July 13, 2011, from Science Daily: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/09/070927121101.htm

Music and the Brain. (2007). Retrieved July 25, 2011, from The Neurosciences Institute: http://www.nsi.edu/index.php?page=xii_music_and_language_perception

Music and the Brain. (2011, July 13). Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_and_the_brain

O’Donnell, L. (1999). Music and the Brain. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Boethius: http://www.cerebromente.org.br/n15/mente/musica.html

Pytel, B. (2007, June 20). Brain Function and Music: How does music affect the brain and learning? Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Educational Issues Suite 101: http://www.suite101.com/content/brain-function-and-music-a22750

Sancar, F. (1999). Music and the Brain: Processing and Responding (A General Overview). Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Serendip: http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/bb/neuro/neuro99/web1/Sancar.html

Sound recording and reproduction. (2011, July 13). Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_recording_and_reproduction#Origins

University of Goldsmiths London (2010, January 16). How music ‘moves’ us: Listeners’ brains second-guess the composer. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from http://www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2010/01/100115204704.htm

University of California – San Diego (2009, May 20). Tone Language Is Key To Perfect Pitch. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from http://www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2009/05/090519172202.htm

Vaneechoutte, M. & J.R. Skoyles (1998). The memetic origin of language: humans as musical primates. J. Memetics – Evolutionary Models of Information Transmission 1998;2. https://users.ugent.be/~mvaneech/Vaneechoutte%20&%20Skoyles.%202000.%20Origin%20of%20language.pdf

Wang, D. (2002, Jan 4). Music, Language and the Brain. Retrieved July 25, 2011, from Serendip: http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/biology/b103/f01/web1/wang.html

I love Music and I am enchanted to be able to read all your articles. Thank you.