Johann Strauss II

Abschied von St. Petersburg (1858)

An der schonen, blauen Donau (The Beautiful Blue Danube), Op. 314 (1867)

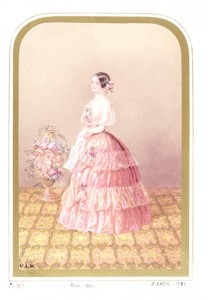

I am not entirely sure who coined the saying “like father, like son”, but they certainly could have had Johann Strauss the father, and Johann Strauss the son in mind. Like any good son, junior tried to outdo his father in all aspects of life, particularly in music and sexual promiscuity. And like any good father, senior desperately tried to prevent his son from duplicating his own mistakes. That’s probably the reason senior insisted that his son — despite displaying remarkable musical skills at an early age — become a banker. But with senior Strauss frequently out of town to regale the European countryside with his musical and sexual prowess, junior secretly took violin lessons. Once senior left the family to have his trousers mended by the seamstress Emilie Trampusch, junior quickly begun to study music in earnest, and by the tender age of 19 established his own dance orchestra, competing directly with the band of his father. The “new Strauss” mesmerized Viennese audiences, and in a blatant repeat of history, Vienna’s female population would swoon at the mere mention of his name. Once his father passed away, junior merged both orchestras, and took the show on the road. His annual summer pilgrimages to Russia were highly successful, however, his popularity with the ladies soon got him into trouble. On more than one occasion, jealous husbands challenged him to duels, and once he even had to seek refuge in the Austrian Embassy, barely escaping a double-barrel shotgun gently inviting him to marry a young Russian maid. Regardless, during his first Russian tour, he passionately fell in love with the young Russian aristocrat Olga Smirnitskaya. The wedding dress was selected, bells were ringing and the honeymoon bed extensively used, yet junior Strauss had somehow forgotten to get permission from Olga’s parents. Not surprisingly, the aristocratic Russians told the Austrian commoner to get lost. Olga quickly fell in line with her parents, and a dejected junior Strauss composed his doleful

Abschied von St. Petersburg (Farewell from St. Petersburg).

Once he arrived back in Vienna, he distracted himself by bedding dozens of eager groupies, occasionally promising marriage, but always dissolving the engagements. One faithful evening, junior Strauss met Henrietta “Jetty” Treffz, mistress to the banker Moritz Todesco. She had born Moritz seven illegitimate children, and spent a total of eighteen years as the other woman. Yet “Jetty” was also an acclaimed mezzo-soprano, and both Berlioz and Mendelssohn had dedicated songs to her. She knew George Sand and the Comtesse d’Agoult, and her own performing career had seen her warble in England, France and beyond. She was seven years older than junior Strauss, but in 1862 they married in the Stephansdom in Vienna. The Viennese public was outraged and the imperial court dismayed, yet they were the perfect couple. While “Jetty” managed the domestic front, which included the copying of orchestral parts and all financial matters, her husband focused on his career. In fact, she was not only the loving and supportive wife, but also junior’s business manager. In addition, she began to channel junior’s creative powers, and urged him to engage with the operetta and other stage works. Junior Strauss still managed to squeeze out the Blue Danube — originally in a ghastly version for male chorus—but his stage career began with the comparatively little known Indigo und die vierzig Räuber (Indigo and the 40 thieves). Soon his most famous operetta Die Fledermaus (The Bat) followed, and a highly successful tour of the United States with concerts in Boston and New York turned junior Strauss into an international superstar. He became universally known as “The Waltz King”, and we can unabashedly say that the time of his marriage to “Jetty” revealed his finest creative period. On 8 April 1878, “Jetty” received a disturbing letter from one of her illegitimate sons. Although the exact content of the letter is unknown, it triggered a massive coronary attack, and she passed away within minutes. Junior Strauss was devastated and couldn’t even bring himself to attend the funeral. Instead, he insistently frequented the local bordellos and a mere seven weeks after the funeral he was married again; but more about that in the final installment of Danubian Debauchery.