Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Niccolò Paganini © eshelmanartcca.blogspot.hk

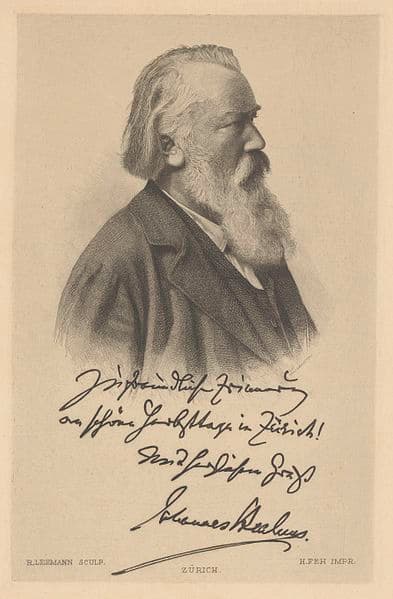

Contemporary young composers of classical music are frequently taken to task for placing marketability and profit orientation above artistic integrity and compositional skill. In reality, however, placing the emphasis on the profitability of a given composition is not really a 21st century phenomenon or invention. Take for example Sergei Rachmaninoff. As soon as he put the finishing touches on his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, he rather nonchalantly remarked, “This piece is for my agent.” Clearly, if we can trust Rachmaninoff’s self-assessment, the composition appears rooted in economic reality rather than an overpowering artistic need for expression.

When Rachmaninoff hastily departed Russia on 23 December 1917 — never to return —he was at the height of his fame as a composer, conductor and pianist. He was quickly offered the music directorships of the Cincinnati and Boston Symphonies, but declined both offers. With no income from his prewar Russian music, which was not subject to international copyright, he resigned himself to the life of a full-time traveling piano virtuoso. Aged forty-five, his creative powers were seemingly on the decline as well. He completed the nine Études-Tableaux, Opus 39, and a couple of small piano pieces in 1917. But then there was nothing coming from his pen for almost ten years. His next finished composition, the Fourth Piano Concerto, which did not find favor with audiences and critics alike, dates from 1926! Rachmaninoff was clearly in need of a chartbuster!

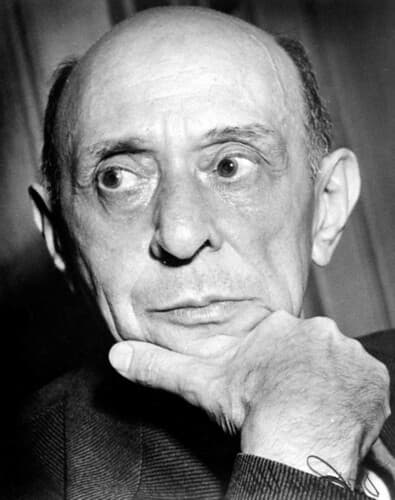

To revive his fortune, Rachmaninoff selected an old warhorse of the classical repertory, the last of the 24 Caprices for solo violin by Nicolò Paganini. As “Caprices” go, they are short, étude-like compositions that confront various technical and interpretive aspects. In this case, the work is a textbook example of classical harmony — actually exposing the bare bones of its tonal simplicity — by gentle shifting from the tonic to dominant key and returning to the tonic. The second half presents a simple modulation via the circle of fifths, and a rhythmically accelerated and ornamented version of the melody concludes this charming little piece. Franz Liszt had stumbled onto this little gem in 1838, and transcribed it for piano. But it really achieved lasting musical fame in the hands of Johannes Brahms, who fashioned two monumental sets of solo-piano variations on the Paganini theme in 1863. By the early 20th century composers and performers such as Ignaz Friedman, Mark Hambourg, Eugène Ysaÿe and Nathan Milstein had all produced characteristic versions of their own.

Sergei Rachmininoff © www.wnyc.org

Thus in 1934, Rachmaninoff set to work and fashioned a miniature piano concerto consisting of 24 variations on the Paganini theme in a mere 6 weeks. Although tightly organized and unfolding with a sense of great drama, Rachmaninoff emphasized the free and rhapsodic unfolding of the theme. The work opens with a free introduction, which is followed by Variation 1, the theme itself. Variations 2-5 are intensely energetic and increasingly excited, with the rhapsodic Variation 6 providing the transition to the introduction of a new theme. This new theme emerging in the piano turns out to be the old funeral chant from the Catholic Mass for the Dead, the “Dies irae” (Day of Judgement.) Throughout Rachmaninoff’s oeuvre, the “Dies irae” had stood as a musical symbol of doom and judgment; in this case it provides stability and a sense of strength and seriousness to the kaleidoscopic variations on the Paganini theme. Variations 8 and 9 hauntingly explore the demonic qualities of the chant, while Variation 10 sounds a grotesque march. Variations 11 through 17 impart a sense of ethereal and subdued longing, sentiments only momentarily interrupted by the fiery 13th and the lively 15th variation. Variation 18 is the emotional centerpiece of the work. It is based on an inversion of Paganini’s melody, and it has undoubtedly become one of Rachmaninoff’s most recognized and most memorable themes. Via a brief transition, Rachmaninoff launches into the final 6 exciting and virtuosic Variations, all climaxing in the ominous blast of the “Dies irae” in the brass.

Rachmaninoff played the piano part at the premiere in 1934, accompanied by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Uncharacteristically, Rachmaninoff was rather jittery and nervous prior to his performance. The story is told that had a glass of crème de menthe to steady his nerves. Everything went spectacularly well, and prior to every subsequent performance of the Rhapsody, he drank a glass of crème de menthe. It is not surprising therefore that the local press — not merely for musical reasons — started calling the piece the “Crème de Menthe Variations.”

…weird title … stage fright ? People might misunderstand what was really going on… Rachmaninoff was 61 years old when he wrote the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini … Well … How many pianists are able to play that particular piece of music ? And by “pianist“ we mean -good concert pianist and not just anybody who dares to call himself a pianist …How many of them ( good concert pianists! )are 60 or even older than 60 years old? “The 24th and last variation of the Rhapsody presents considerable technical difficulty for the pianist” … considerable technical difficulty for the pianist !… and only then we read: “The 24th and last variation of the Rhapsody presents considerable technical difficulty for the pianist, and shortly before the Rhapsody’s world première performance, Rachmaninoff confessed trepidation over his ability to play it. Upon the suggestion of his friend Benno Moiseiwitsch, Rachmaninoff broke his usual rule against drinking alcohol and had a glass of crème de menthe to steady his nerves. His performance was a spectacular success, and prior to every subsequent performance of the Rhapsody, he drank crème de menthe. This led to Rachmaninoff nicknaming the twenty-fourth the “Crème de Menthe Variation”

I like the short, analytical description of each Variation given above. And was always impressively amazed at how the Composer took a Paganini theme which didn’t sound like it had enough substance to be turned into such a “miracle” by Rachmaninoff, who DID remark that that Variation might “save” the piece. But, even with that beautiful Variation, for me – there did not seem to be sufficient dramatic appeal, (though certainly virtuosic on a less deep level) to feel prompted to study it.

In fact, Rachmaninoff’s laconic remark….”this one I wrote for my agent” refers to the celebrate 18th variation, not the whole work. Benno Moiseiwitsch recommended the crème de menthe half-jokingly, knowing his great friend was superstitious and would believe in the remedy, this was at BM’s club in London, well after the US premiere.

Misleading to imply that Rachmaninoff “needed” a chartbuster. According to correspondence it was after hearing his friend Fritz Kreisler practising that the Paganini 24th caprice got obsessively into his head. At his Lake Lucerne Villa Senar, he had the time, leisure and inspiration to create a work of pure genius.

Paul, do you happen to know of which London Club dear Benno was a member?

One of my earliest memories (age 7) is when the family attended a concert by Sergei at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor. All solo piano, no orchestra. [Afterwards, we were invited to a reception where my Mother noticed that I had somehow managed to put on a pajama top instead of a shirt. Fortunately, nobody else commented.]

It’s a great story. Personally I doubt that SR touched a drop of alcohol before performing. Sadly, even the only pianist I would mention in the same breath as SR – Josef Hoffmann – did develop a dependency in the 1940s but his playing declined markedly at that point.