Is it true that success removes inspiration and the drive to create and explore? If it does not happen to all, it is certainly observable with many. Particularly with recent composers and artists. Throughout the first quarter of the 21st century, there has been a rise in popularly successful classical composers, mostly thanks to film music. However, as we slowly reach the end of it, we can also observe a recurring pattern in their success and creative curb; they move in contrary motions. As success grows, inspiration seems to decline.

© personalityjunkie.com

Ludovico Einaudi: Elements

The explanation for this phenomenon seems quite simple enough, though. In order to illustrate, let’s look at some of the most successful contemporary composers today, namely Einaudi, Richter, Zimmer, and Tiersen. Four composers from four different countries which have reached similar levels of fame and achievement. All of them have composed for films and are globally well-known, some more than the others. Now in the second half of their lives – they have spent most of it building their momentum – and having released some of the most exciting pieces of the 21st century. However, their pinnacle seems to have now passed.

Ludovico Einaudi © Decca/Ray Tarantino

Einaudi has stopped taking musical risks since Elements in 2015. Richter’s last venture into innovation was with Sleep in 2015, and before that, Recomposed 2012. Zimmer’s composing style seems to have stagnated since Inception in 2010. Whilst Tiersen aims at reproducing the success of Amélie’s soundtrack, initially composed between 1995 and 2001.

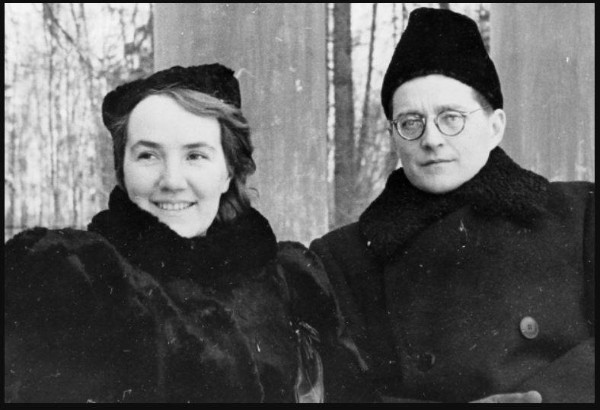

Max Richter © Wikipedia

So, what changes from before and after success? The first answer is the following: when an artist is desperately trying to make ends meet, he looks for as many options as possible. He responds positively to almost anything that is offered to him. His goal is to produce and create in order to find what will make him successful to the ears of others. He is also deeply in the process of developing his own self, finding his own musical personality. Then, eventually, the artist finds success, and that success is often in the past year’s work — often one specific work. One of these works has made the cut and this will become the stamp for the success of the artist. Therefore, this is what the audience likes from the artist, and this is what the audience will ask for.

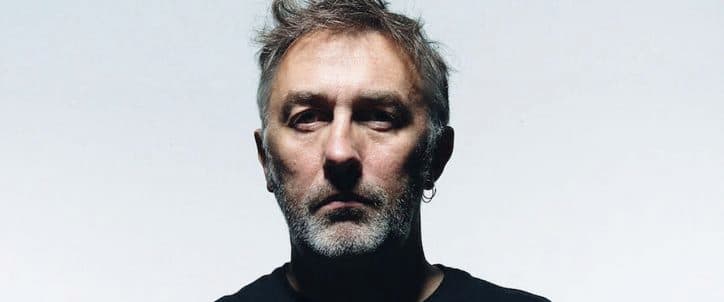

Hans Zimmer © Wikipedia

But the artist has moved on from that. And he then enters a vicious circle; either the artist breaks from this circle and risks losing all achievements, or the artist accepts to repeat himself in order to give what the audience wants and what allows the artist to survive. The artist then enters a tunnel of repetitions which he has to go through in order to be liberated once again — once sustainability is not an issue anymore and the artist can get back to being free to create for the sake of creating. Some artists get stuck in the tunnel. Some escape.

Max Richter: Dream 3

Yann Tiersen: La Valse D’Amelie

The bitter-sweet success is not exclusive to art and music of course, and one can observe this reaction to innovation and progress in many other career worlds. An observable similar consequence can be seen in the innovation of Apple and its products declining as the company grew. It seems that sales and progress are not to be seen together. In popular music, the tunnel is almost never-ending. The end of the tunnel means the end of any sort of success.

Yann Tiersen © whatthefrance.org

This is why popular artists who challenge themselves — Sting, for instance — go through moments of ups and downs and find successes and failures as they evolve. On the opposite end of the scale, Cage, who is one of the most innovative composers of the 20th century, seldomly found public success whilst alive and ended his life in as much poverty as he started it; however, he has never seemed to lose inspiration and the thirst to explore. Inspiration is an interesting fact. Some say it is a blessing that cannot be controlled; others say it is a practice that can be maintained over time. One must differentiate inspiration with innovation as it is possible to feel inspired, but to repeat oneself over and over.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter