5 Gedichte fur eine Frauenstimme, Op. 91, “Wesendonck-Lieder”

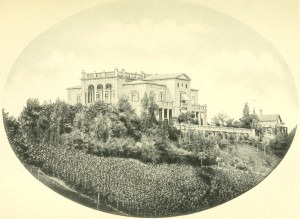

The beautiful and talented poet and playwright Agnes Mathilde Luckemeyer married the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck in 1848. The couple moved to Zurich and Otto, having done extremely well in his profession, ordered the construction of a lavish villa, harmoniously situated in a sprawling park in the center of the city. Otto spared no expense in furnishing his new home, providing a lush marble interior, blush carpets, exotic tapestries, luxurious curtains and delectable furniture.

The beautiful and talented poet and playwright Agnes Mathilde Luckemeyer married the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck in 1848. The couple moved to Zurich and Otto, having done extremely well in his profession, ordered the construction of a lavish villa, harmoniously situated in a sprawling park in the center of the city. Otto spared no expense in furnishing his new home, providing a lush marble interior, blush carpets, exotic tapestries, luxurious curtains and delectable furniture.

On 25 April 1853, the happy couple went to a concert at the Aktien-Theater and heard music composed and conducted by Richard Wagner. Otto was immediately fascinated by Wagner’s music, and Richard initially fancied Otto’s money, and a little later Mathilde as well. Almost immediately, Otto began to provide substantial financial contributions to Richard and Minna, and Richard thanked him by composing a piano sonata, which he dedicated to Mathilde. By 1857, the Wesendonck mansion was completed, and Otto placed the 2-story cottage — adjacent to the villa on his estate — at Richard’s disposal. Since money does not grow on trees — a concept Richard Wagner really never fully comprehended — Otto went on frequent and extended business travels, and Richard took over the villa. He hosted lavish parties and invited friends from near and far to stay for indefinite periods of time. Even the newlyweds Cosima Liszt and Hans von Bülow visited the self-anointed lord of the manor. And you are absolutely right in suspecting that Cosima Liszt/Bülow will eventually become Cosima Wagner! Of course, Richard was not only using Otto’s villa and drinking his champagne; he was also having his ways with Mathilde. She became his “Isolde,” showered him with perfume, and provided him with all the silk undergarments a real man could ever have. His infatuation was boundless, and he composed the Wesendonck Lieder, based on five of her poems, for his “sacred angel.” Yet things got complicated when Minna intercepted a letter from Richard to Mathilde in April 1858. “The day before yesterday, an angel came to me at noon, blessed and comforted me,” he wrote. “Now I am able to pray to my angel with heartfelt emotion. This praying is a prayer of love. Love! Profound joy in this love, it is the source of my salvation. When I look into your eyes, there is nothing more to say. I feel so sure of myself when this wonderful, sacred gaze falls upon me and envelops me…” Minna was mightily impressed, and showed the letter to Mathilde, and subsequently to Otto as well. In his defense, an indignant Richard claimed that Minna had put a “vulgar interpretation” on his letter, but Otto would have none of it and kicked the composer out.

Wagner left for Venice, and Minna went to Dresden. Before departing Minna rather sarcastically wrote to Mathilde, “I must tell you with a bleeding heart that you have succeeded in separating my husband from me after nearly twenty-two years of marriage. May this noble deed contribute to your peace of mind, and to your happiness.” Minna continued to take the view that Mathilde had seduced her Richard, and kept referring to her as “that filthy bitch,” and “that hussy.” Richard, of course, was more concerned about his financial support drying up, and for a while he continued to write lavish “fantasy love letters” to Mathilde. Six years later, with Richard once more in dire financial straights, he asked Otto to be allowed to live in the Wesendonck cottage once again. After Otto had stopped laughing, he told him in no uncertain terms to bugger off! Richard was highly offended, and writes: “The unpleasantness that separated me from you about six years ago should be evaded; it has upset me and my life enough that you recognize me no longer and that I esteem myself less and less. All this suffering should have earned your forgiveness, and it would have been beautiful and noble to have forgiven me; but it is useless to demand the impossible, and I was in the wrong.” It is rather characteristic of Wagner to regard his sufferings as much more important than those of the husband whom he had wronged. In his autobiography, dictated to his later wife Cosima, Richard describes his affair with Mathilde Wesendonck as “something of a mystery.” Despite their “Wagner Experience,” the Wesendonck’s continued to support the arts and various artists. Among them was Johannes Brahms, who visited Zurich for a number of performances between 1865 and 1866. Brahms did lodge in the Wesendock cottage, but politely refused the invitation to move in.

Wagner left for Venice, and Minna went to Dresden. Before departing Minna rather sarcastically wrote to Mathilde, “I must tell you with a bleeding heart that you have succeeded in separating my husband from me after nearly twenty-two years of marriage. May this noble deed contribute to your peace of mind, and to your happiness.” Minna continued to take the view that Mathilde had seduced her Richard, and kept referring to her as “that filthy bitch,” and “that hussy.” Richard, of course, was more concerned about his financial support drying up, and for a while he continued to write lavish “fantasy love letters” to Mathilde. Six years later, with Richard once more in dire financial straights, he asked Otto to be allowed to live in the Wesendonck cottage once again. After Otto had stopped laughing, he told him in no uncertain terms to bugger off! Richard was highly offended, and writes: “The unpleasantness that separated me from you about six years ago should be evaded; it has upset me and my life enough that you recognize me no longer and that I esteem myself less and less. All this suffering should have earned your forgiveness, and it would have been beautiful and noble to have forgiven me; but it is useless to demand the impossible, and I was in the wrong.” It is rather characteristic of Wagner to regard his sufferings as much more important than those of the husband whom he had wronged. In his autobiography, dictated to his later wife Cosima, Richard describes his affair with Mathilde Wesendonck as “something of a mystery.” Despite their “Wagner Experience,” the Wesendonck’s continued to support the arts and various artists. Among them was Johannes Brahms, who visited Zurich for a number of performances between 1865 and 1866. Brahms did lodge in the Wesendock cottage, but politely refused the invitation to move in.

More Love

- Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music? - Louis Spohr and Dorette Scheidler

Magic for Violin and Harp "Shall we thus play together for life?" - Zdeněk Fibich’s Erotic Diary: Moods, Impressions and Reminiscences A Musical Journey of Passion and Obsession