The history of Christmas makes fascinating reading. Christmas, as we know, is the annual celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. For the most part, it is observed on December 25, but as with a good many other religious holidays, that date only came about after a good deal of discussion. We don’t get a precise date for Christmas in the gospels of Luke and Matthew, but we know that Jesus was born in Bethlehem to the Virgin Mary. In the gospel of Luke, Joseph and Mary traveled to Bethlehem, and Jesus was born and placed in a manger, with angels proclaiming him a savior of all people. It was up to early Christian writers to suggest various dates for the anniversary of the birth of Jesus. As early Christians connected Jesus to the sun, the first recorded Christmas celebration was held in Rome, on the day of the winter solstice, on 25 December 336. However, that date was the subject of great debates.

Anonymous: Viderum Omnes (Monks and Choirboys of Downside Abbey; David Lawson, cond.; Dom Dunstan O’Keeffe, cond.)

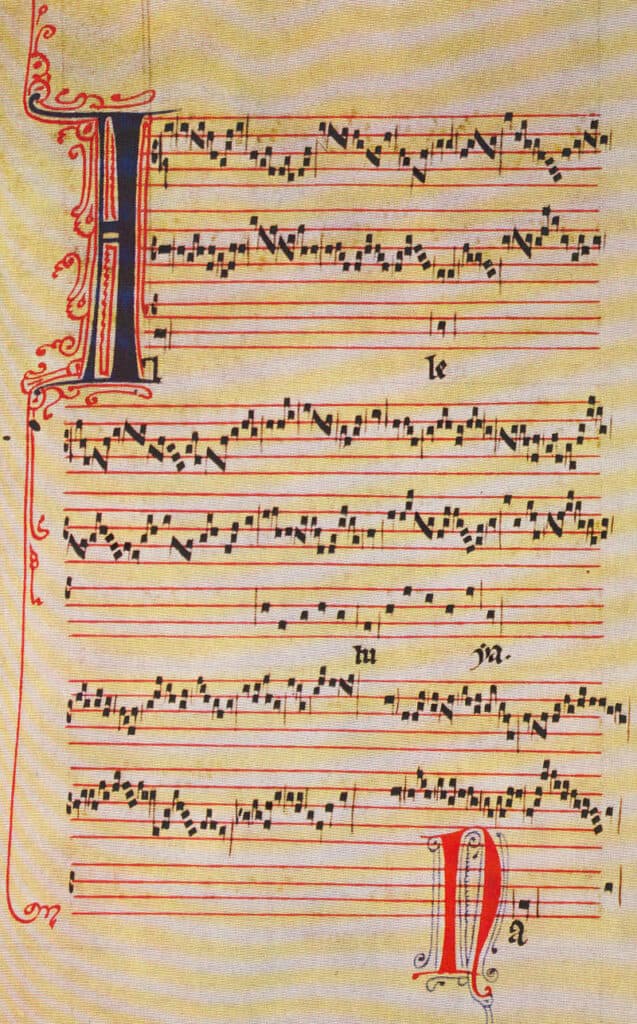

Pérotin: Viderunt Omnes

An early Christian writer observed around the year 200, “there are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord’s birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of the Egyptian month Pachon on May 20… Further, others say that He was born on the 24th or 25th of Pharmuthi, on 20 or 21 April.” However, once the date of 25 December had been established, Christmas was pretty well forgotten, greatly overshadowed by the importance of Easter. The feast only regained prominence after the year 800 when Emperor Charles the Great, also known as Charlemagne, started to unite the majority of western and central Europe. A firm supporter of the papacy, he Christianized the unified lands, and codified many aspects of Christian worship, including liturgical texts, prayers, and music.

Pérotin: Viderunt Omnes (Kronos Quartet)

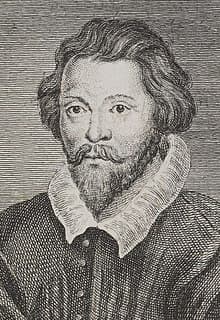

William Byrd

And this brings us to “Viderunt omnes,” a Gregorian chant that was sung at the Masses of Christmas Day and also on the Feast of Circumcision. The prayer has a clear Christmas flavor by focusing on the revelation of God’s righteousness. However, the reason the text has become famous is found in the fact that two musical settings from the 12th century, by the Parisian monks Léonin and Pérotin, are among the earliest pieces of polyphony written down by known composers. Thereafter, the melody and text have been set multiple times, including a beautiful motet setting by William Byrd.

All the ends of the earth have seen

the prosperity of our God.

Rejoice in the Lord, all lands.

The Lord has made known his prosperity;

in the sight of the nations

he has revealed his righteousness.

William Byrd: Viderunt omnes (Christ Church Cathedral Choir, Oxford; Stephen Darlington, cond.)

The same process guided multiple settings of Dies sanctificatus, the Alleluia verse text for Christmas Day. The text is partly drawn from Psalm 117:24, and the connection to Christmas is unmistakable.

A day made holy dawns upon us;

O come, all nations, and adore the Lord;

for today a great light has descended upon earth.

Alleluia.

This is the day the Lord has made;

let us be glad and rejoice in it.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Dies sanctificatus (The Sistine Chapel Choir; Massimo Palombella, cond.)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

I am not sure when Dies sanctificatus was first treated polyphonically, but it was certainly set by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, also known as the “Savior of Church Music.” His music became sounding documents of the Catholic Reformation, a movement in direct response to the Protestant Reformation. The papacy sought to reorganize the ecclesiastical and political structures of the church, establish religious orders and restore the spiritual foundations of Catholicism. Many of the reforms focused on music, trying to purge inappropriate behavior of church musicians and inappropriate use of instruments. One of the main points of contention was the use of complex polyphony that made it impossible to understand the words. Popular legend suggested that Palestrina saved polyphony from condemnation by composing a six-voice mass that did not obscure the text. It’s probably just an anecdote, but Palestrina’s superb and open contrapuntal style never obscures the words in his masterful Christmas motet.

Heinrich Isaac: Dies sanctificatus (Vienna Boys Choir; Choralschola der Wiener Hofburgkapelle; René Clemencic, cond.)

Joseph Eybler

The featured setting by Heinrich Isaac predates Palestrina’s motet by many decades. Isaac was one of the most prolific composers of his time, and the vast majority of his motets were composed to Latin texts. The ancient chant Dies santificatus is set as a fixed melody, with the texts of the free voices mirroring the original prayer. Joseph Eybler is probably best remembered for being asked by the widow Constanze Mozart to complete her late husband’s Requiem. Eybler did start the task, but because of his great respect for the music of his good friend Mozart, he passed the work to Franz Xaver Süßmayr. Eybler was an excellent choice, because he was a well-known composer of sacred music. He held appointments as choir director of the Carmelite Church in Vienna, and was appointed court Kapellmeister. The Empress Marie Therese was particularly fond of his composition and commissioned a number of works, including a Requiem in C minor. Among his catalogue of works we also find a delightful setting of the Dies sanctificatus.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Joseph Eybler: Dies sanctificatus (The Cathedral Singers; Richard Proulx, cond.)